Born in Manchester in 1973, Nigel Cooke is a painter of repute, and an academic with a research background in philosophy and a wide range of interests that span interdisciplinary subject areas.

Drawing from sources as diverse as art history and palaeontology, classical mythology and neuroscience, Cooke is best known to the general public for his large-scale work straddling the formalistic boundaries between abstraction and figuration.

Often employing different techniques – from trompe-l’œil to “flying white”, a Chinese brush technique used to convey a sense of speed and spontaneity – the artist creates compelling compositions that merge seemingly contrasting elements into pictorial narratives whose ambiguity and complexity are heightened through a dramatic and equally distinctive use of colour.

Informed by travels and encounters with wildlife at home and overseas, Cooke’s latest body of work – which was recently put on show at Pace, London, in an exhibition called Atlas with Butterfly – reveals a further shift towards a perhaps more abstract, gestural and succinct style.

Reflecting the artist’s interest in the ways the act of painting mirrors our relationship to nature, the series depicts intricate webs of ribbon-like fibres stretching in all directions, entangled clusters of ropes and bundles that conjure up a variety of imagery of the natural world – from neural networks to crashing waves, from stylised flagella to vibrating string-like plasma filaments.

1883 Arts Editor met with Nigel Cooke to find out more about his work and inspiration.

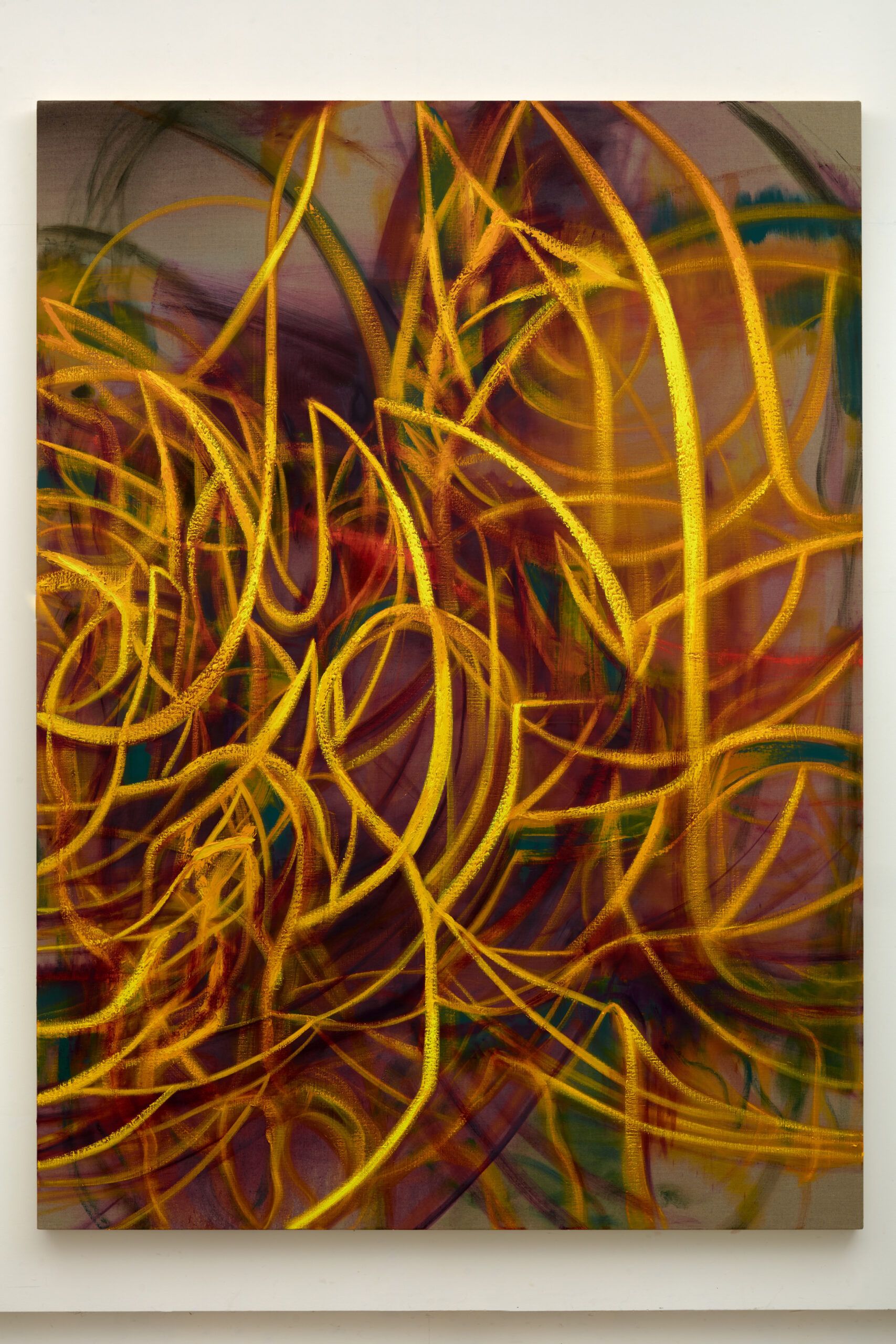

Nigel Cooke, Pantera, 2022 oil and acrylic on linen, 225 cm × 164 cm (88-9/16″ × 64- 9/16″) © Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery Photo: Robert Glowacki

Nigel Cooke, Pantera, 2022 oil and acrylic on linen, 225 cm × 164 cm (88-9/16″ × 64- 9/16″) © Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery Photo: Robert Glowacki

Thank you for agreeing to the interview.

Can you tell us a bit about your recent show at Pace? What was the inspiration behind it?

The show was the result of about a year’s work, and looking back, I can see that the central preoccupation was colour.

There were many ideas that played in and out of the process, but that’s something that separates this from previous shows. I didn’t really understand that clearly before, but that’s how it always is for me – I work to understand what the work is about; the point of a show only really crystallises at the end. Until then, it is all instinct, guesswork.

I prefer this, I love the feeling of being lost in a vague problem of my own making. To me that’s a kind of daily inspiration too, the process of trying to make a painting happen. In more realistic terms, a point of inspiration was a trip to Miami, where I was struck by certain colour effects in the sky and water that I hadn’t seen before, as well as the way people stood around looking at it, very still.

Sometimes it is the observed colours themselves that I’m trying to recapture, but at others it’s more the feeling of power that emanates from colour, how colour combinations become almost sonic in their harmonies, a sort of pulsation or mantra that stops you where you stand.

If I remember correctly, it was the sighting of a pelican landing on the ocean that prompted you to start working on the paintings featured in Atlas with Butterfly; what was it about that scene that spurred you into painting, if I may?

If the colour theme could be called the environment of the paintings, the sighting of the pelican is the energy of the paintings, their force of movement. I was interested in this incredibly powerful colour field of a Miami sunset, but when a prehistoric, shabby pelican suddenly crashed into the waves when I was busy staring into the distance, there was a vivid clash between two kinds of eternity – the sublime, perhaps mystical endlessness of the vista and the deep time of evolution, prehistory.

In the same moment, it made me think of the Apollonian and Dionysian dialectic of creativity – the balance between perfection and destruction that is at the heart of painting, I think. The scene allowed me to think about heightened colour alongside a kind of blemishing, destructive energy, something that tears down structure as it also strives to rebuild it.

The moment was an example of the tensions in painting that I am most interested in, but phrased as a natural phenomenon, which is what I found most exciting because I still like my paintings to have an anchor in experience and observable life – they are not just about paint. It’s not that I wanted to paint pelicans – more that it reminded me that nature and painting are the same.

Painting to me is all about energy and tension, the forces of life and destruction that are codependent, and the echoes of this throughout deep time.

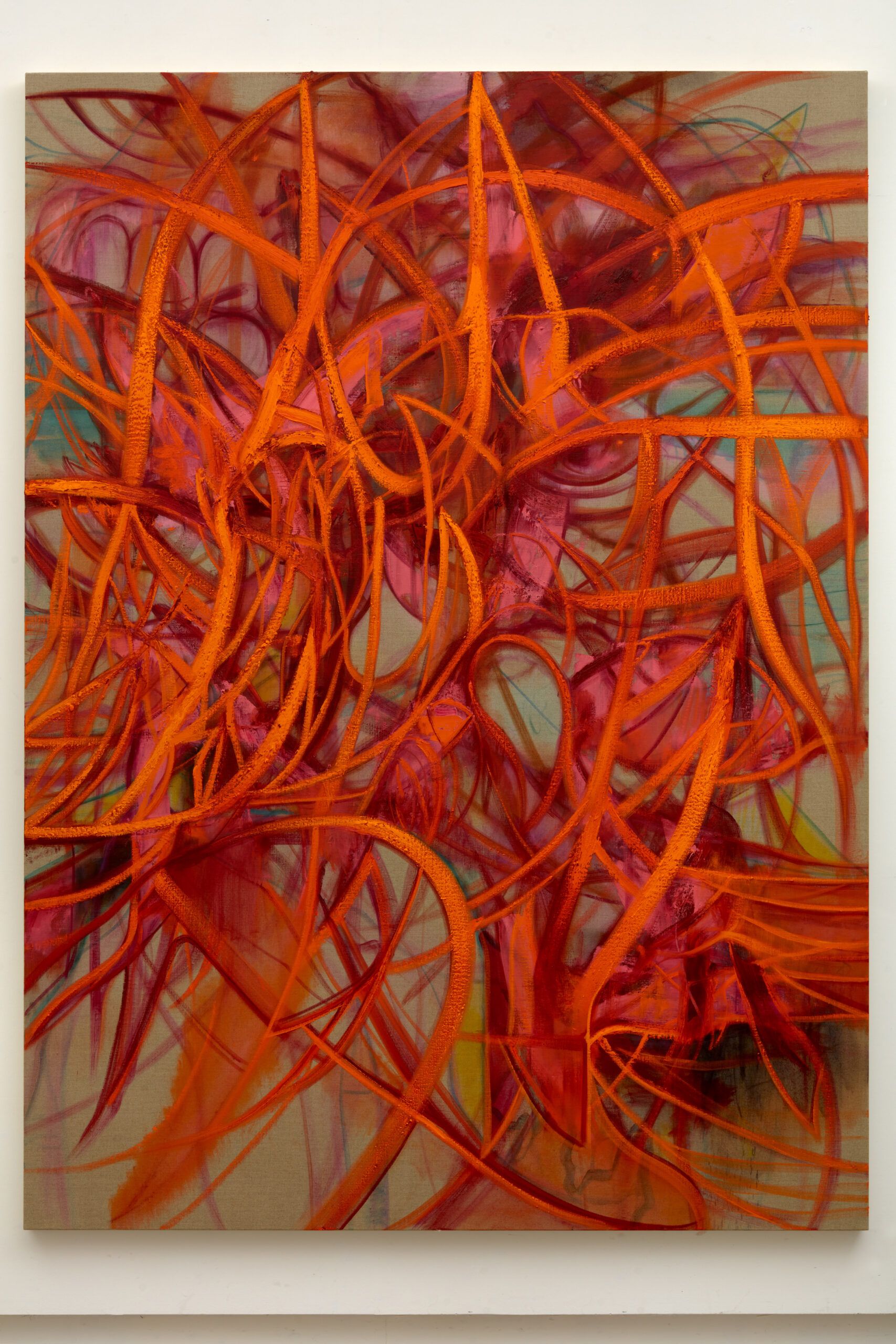

Nigel Cooke, Sula, 2022, oil and acrylic on linen, 225 cm × 164 cm (88-9/16″ × 64- 9/16″) © Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery Photo: Robert Glowacki

Nigel Cooke, Sula, 2022, oil and acrylic on linen, 225 cm × 164 cm (88-9/16″ × 64- 9/16″) © Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery Photo: Robert Glowacki

Out of curiosity, how do you approach the beginning of a new painting? What is your working pattern like?

I usually start with staining and marking the canvas in a very blurry way, in acrylic paint, to feel out the character of the image, what it might be about or where it might be set. These things are just points of departure, but they allow me to make certain decisions. There’s always a location in my mind, even if it’s not obvious in the final image.

These things will just direct me; I will decide if it’s by the sea, in a forest etc, and just explore it from there on its own terms. I never use images or anything like that, but I do use small sketches made on location in various places, if I’m interested in that kind of setting. The vocabulary of my on–the–spot watercolours gets into the compositions, because I like their awkwardness.

You have always played with shifting between abstraction and figuration. Your new works, however, highlight a further shift towards an even more energetic, gestural and perhaps succinct style. May I ask what prompted this change?

Like most things in life the change was gradual and then it was sudden. Looking back, it was obviously trying to break through for a long time, but to me it only became real when I left my studio for a bit and went to New York. It was one of those times when how I felt when making my work and what it looked like somehow didn’t match up. Something had shifted in my thinking, and I needed a fresh perspective to help it become visual.

Succinct is right, I think – I was searching for an all–encompassing language distilled from all my work to date, an extraction of a core element that would give me the ultimate freedom but also consolidate what I had learned so far, both about myself and painting as a relationship.

In a way, where I have arrived at is about compressions and explosions of energy as an articulation of all natural phenomena. It’s always had that aspect, though now it is not hampered so much by the pictorial. In the end I realised that the pictorial dimension was holding back the painting.

As a final question, what does the future hold in store for you?

I have a show coming up in New York in May, with Pace, as well as a publication at some point after that. Beyond that who knows, though I am looking to work overseas again at some point, it has proven to give me a great perspective on things.

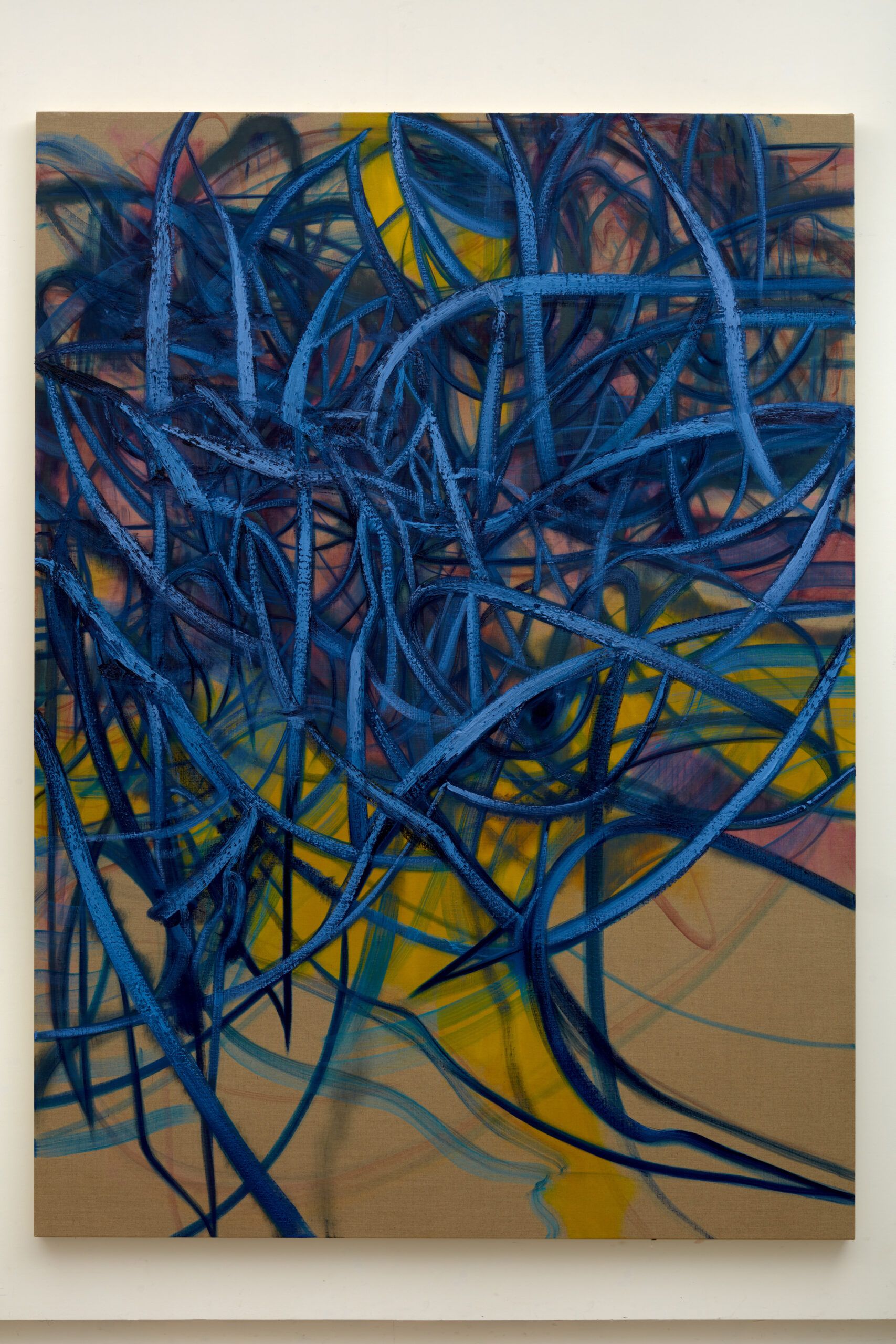

Nigel Cooke, Corvus, 2022, oil and acrylic on linen, 225 cm × 164 cm (88-9/16″ × 64- 9/16″) © Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery Photo: Robert Glowacki

Nigel Cooke, Corvus, 2022, oil and acrylic on linen, 225 cm × 164 cm (88-9/16″ × 64- 9/16″) © Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery Photo: Robert Glowacki

Featured Image: Installation View, Nigel Cooke: Atlas with Butterfly, November 23, 2022 – January 7, 2023, Pace Gallery, London © Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery Photo: Damian Griffiths, courtesy Pace Gallery

Words and interview by Jacopo Nuvolari