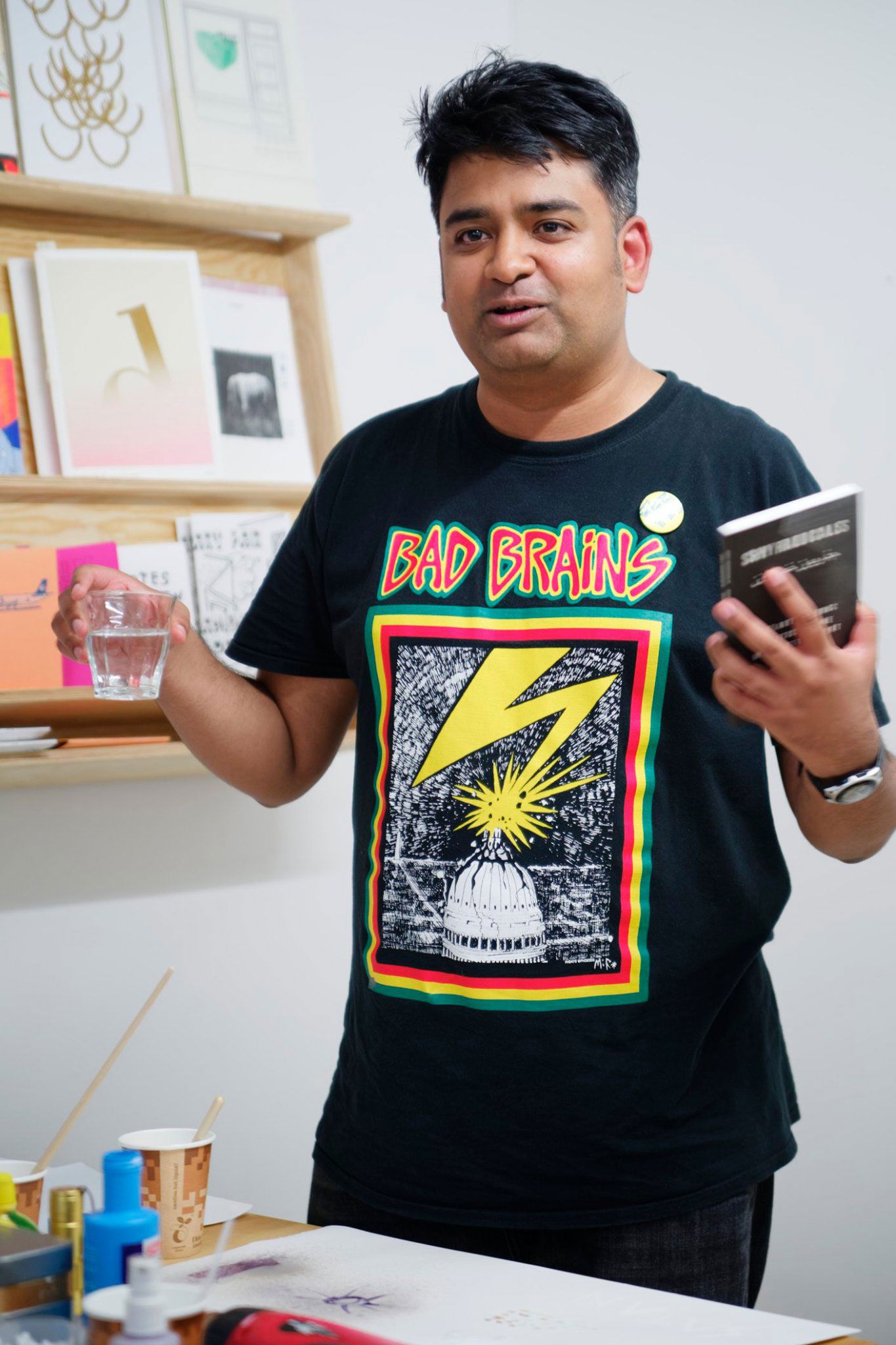

Multi-hyphenate Hamja Ahsan is a wearer of many hats.

Seamlessly moving between creation and curation, the 43 year-old artist, facilitator and activist from London works across a diverse array of media and outlets to address issues of identity, inequality and racial discrimination. Tinged with satire and witty analysis of contemporary society, his practice ranges from conceptual writing, performance and building archives to running workshops, making zines and organising exhibitions.

A graduate from Central Saint Martins and Chelsea College of Arts, Ahsan is perhaps best known to the wider public as the author of Shy Radicals: Antisystemic Politics of the Militant Introvert (Book Works, 2017), a cutting work of speculative fiction that reflects on the inherent violence of the so-called Extrovert-Supremacist world order. Taught at Universities in Britain and the US, in 2020 Shy Radicals was adapted into a movie produced by Ridley Scott’s film company, Black Dog Films, and directed by Tom Dream.

In 2022, Hamja Ahsan was invited to participate in the fifteenth edition of Documenta, the prestigious showcase of contemporary art that has been held every five years in Kassel, Germany, since 1955. Curated by Indonesian art collective ruangrupa and drawing upon ideas of cooperation and collective action, the exhibition set out to shed light on the thorny relationship between capitalism, racism and colonialism, with a focus on artists from the Global South.

While Documenta has certainly never been immune from criticism, the fifteenth edition proved particularly contentious, to say the least. Following the opening of the show, accusations of anti-semitism were soon levelled against curators and artists alike. A ferocious debate – one that still rages two years on – ensued concerning the hostility of post-colonial art practices towards the state of Israel and the Zionist ideology.

Ahsan himself – whose work at Documenta conjured up a universe of competing halal fried chicken franchises to engage with themes of Islamophobia, identity and belonging – became embroiled in a controversy that continues to this day. After having one of his exhibition venues defaced with anti-Muslim slogans, he was the target of a vicious hate campaign by German media and politicians on account of his support for Palestine and the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions Movement (a nonviolent Palestinian-led campaign promoting boycotts and economic sanctions against Israel).

1883 Arts Editor got in touch with Hamja Ahsan to learn more about his time at Documenta and related controversy, and ask about My Brother is Back, a group show curated by the artist at WIP Space Studios in London. Conceived as a prologue to the Shy Radical book and featuring, among others, Shahidul Alam, Tom Dream, Senaka Weeraman and Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan, the exhibition gathers together works of varying mediums to explore themes of racism, extradition and prisoner solidarity.

My Brother is Back takes its name from Uschi Gatward’s eponymous short story that covers the prison ordeal of Talha Ahsan, an award-winning poet and Hamja’s brother. Caught in the crosshairs of the War on Terror, in 2006 Talha was arrested in London following a request from the United States, and subsequently detained without trial or official charge for six years. In 2012, he was extradited to the US and incarcerated in a supermax facility for his association with an Islamic news website concerned with the conflicts in Bosnia, Chechnya and Afghanistan that ran from 1997 to 2001. In 2014, Talha – “a moderate person who has peaceful views” and is “not aligned with the views of people who are violent”, according to US judge Janet Hall – was finally repatriated to the UK after receiving a time-served sentence following a plea-bargain.

During Talha’s time in detention, Hamja and his family never stopped campaigning for his liberation, and received support from the likes of Noam Chomsky, Jeremy Corbyn, A. L. Kennedy and Riz Ahmed. In 2013, the Free Talha Ahsan campaign was shortlisted for the Liberty Human Rights Award for its creative use of art, film and poetry.

Hello Hamja, thank you for finding time for 1883 Magazine. To start with, could you tell us a bit about yourself? What sparked your interest in art? And how did you decide to pursue it as a career?

I’ve wanted to be an artist since I was about three years old. I remember that I used to draw my teachers when I was in preschool. This is an anecdote that my mom, who isn’t particularly connected with my art practice, still tells people when they come to our house.

I graduated from Central Saint Martins as a mature student in 2008; I went to university late. I had been struggling with depression for quite some time before I enrolled at university – I attempted suicide at 17. And the Fine Art degree really helped me to get back into what you might call structured living. At Central Saint Martins I met an Irish artist named Anne Tallentire, who became my tutor. In 1999, she represented Ireland at the Venice Biennale. Tallentire, an Irish woman who experienced racist abuse during the Troubles, was of course deeply sympathetic towards me and my brother, Talha. I had no A levels. I just had my portfolio, and she saw something special in my socially-engaged, conceptual art practice.

Besides being an artist, you are a curator, and a writer. I’m curious, how would you define your curatorial process?

Well, since graduating, I’ve gone in and out of calling myself an artist and not an artist. I have changed my title from artist, to writer, to activist, to curator, and swapped them around at various points in my career.

From 2008 till about maybe 2009, I called myself an artist primarily. And then I actually really wanted to be a curator. The work of Okwui Enwezor, the curator of Documenta 11, and Lucy Lippard in particular really inspired me. So I did a MA in curating at Chelsea College of Arts, which was actually quite a horrible experience. A lot of what we may want to call contemporary curatorial language lacks critical insight. It neither promotes inclusivity nor accessibility. It is dryly academic, dogmatic and terribly homogeneous.

Since I graduated, I have had periods of dejection and depression. As often happens to artists, I’ve been through unemployment and periods of overwork, where I was dealing with, say, up to six patrons from six different countries, simultaneously. It’s mentally draining when you cannot afford studio assistance or administrative support. Art can actually be psychologically unhealthy, especially in this economy. To tell you the truth, I’ve considered leaving the art world multiple times to become a human rights lawyer for prisoners and campaign for justice.

When my book came out in 2017, Shy Radicals, which most people know me for, I basically began to call myself a writer first and foremost. Then in 2019, Slavs and Tatars invited me to the Ljubljana Biennial, where they awarded me the Grand Prize. Before Ljubljana, I hadn’t been in exhibition for years. After the biennial, I began to call myself an artist again.

So to try and answer your question, what I do as a curator is very separate from what I was taught in school. When curation is confined to academia, it becomes masturbatory, vacuous and unilluminating. My curatorial process involves being embedded in communities and building my own collections and archives. I’m also very much into zine and DIY culture, and that’s the bedrock of everything. To tell you the truth, I don’t even think of myself as a curator. I think of myself as a player manager. It is my opinion that we can borrow curatorial patterns, motifs, modes of thinking from everywhere. Everyone curates. My mum curates; anyone who selects and categorises is a curator. Curating is not just for fancy people from elite Universities.

Can you tell us about My Brother is Back, the exhibition you’ve curated at WIP Space Studios in London?

My Brother is Back is an archival exhibition. It features works from artists and creatives who took part in in the Free Talha campaign against the unjust extradition and detention of my brother, Talha Ahsan.

The exhibition brings together ceramics, sculptures, figurative painting, photos, flyers, zines. It also showcases my early conceptual text pieces, and the jackets and campaign T-shirts that I wore on my demonstrations. The centrepiece is a film I made in collaboration with Tom Dream and Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan. It’s titled Kindness vs. the Home Office and reflects on state violence.

The exhibition space also accommodates a library and a reading room with posters, flyers, publications about state crimes and prisoner solidarity, as well as a collection of zines, including the first one I made when I was a thirteen year old “revolutionary” in the 1990s, titled Nausea.

My Brother is Back reflects on Islamophobia, extradition and prisoner solidarity. I wonder, how does this exhibition resonate with your own personal experiences?

Throughout my career, I have repeatedly engaged with issues of Islamophobia and xenophobia. My book, for instance, Shy Radicals, which is at one level about introversion and extrovert supremacy, is in fact a satire that provides a critique of dominant culture to shed a light on the rising tide of anti-Muslim sentiment.

Humour is really important in my writing and performance work. Sometimes I’d rather be a stand-up comedian than an artist! When I was toying with the idea of Shy Radicals, I soon decided to take a comedic approach to writing the book. At its top, the art world is concerned with profit-and-loss and donors, and it is completely removed from any grassroots struggle.

So back to the exhibition. We could say My Brother is Back – which, as you were saying, also reflects on extradition and prisoner solidarity – is very much like a prologue to Shy Radicals. The very first chapter I wrote for the book was about a fictional political prisoner who is arrested and detained without trial.

As you know, I’ve spent many years campaigning for unlawfully detained prisoners. I even campaigned with the Angola Three. I’ve had a lot of intense conversation with legendary radical lawyers such as Gareth Pierce, Louise Christian, Clive Stafford Smith. And all the demonstrations and marches and conversations came to inform Shy Radicals. So every fan of Shy Radicals, and I know they are many, should really come to the exhibition.

What would you like audiences to take away from the show?

There’s a story behind each artwork on display. Behind each book. I would like the visitors to read the books and look at the works, and leave the show with a desire to delve deeper into the issues My Brother is Back addresses. I want the exhibition to enhance their critical thinking. Because I want them to question what they read in the papers, what the government tells them.

Also, I would like them to become involved in the campaigns against solitary confinement. And, most importantly, I would like them to spare a thought for all the people who’ve sacrificed and struggled to defend civil liberties and human rights.

Speaking of personal experiences, I would like to ask you about your time in Germany during Documenta 15. The 2022 edition of the exhibition was at the centre of a heated row over claims of anti-semitism. Can you tell us what happened? After an online exchange with Stefan Naas, a politician from the Freie Demokratische Partei (Free Democratic Party, or FDP), I read you became the target of a relentless hate campaign by several German media outlets that lasted months. Did you draw any personal support from Documenta or other major art institutions, German or otherwise, during this time? What does the Documenta controversy tell us about the art scene in Germany, and the country in general? And why do you think post-colonial theory and art get equated with anti-semitism?

Well actually, the hate campaign started even before Documenta. Someone broke into my exhibition venue and vandalised it just days ahead of the opening bash. They sprayed the name of a Spanish neo-Nazi youth leader all over the walls. In Germany, anti-Muslim and anti-Palestinian sentiments have been on the rise for quite some time now. Hatred began to rear its ugly head long before Documenta fifteen opened its doors in June 2022.

In 2019, for example, the German parliament passed a resolution that labelled the Palestinian Boycott Divestment and Sanctions Movement, which is a non-violent organisation, as anti-Semitic. The FDP has recently called for banning Al Jazeera for allegedly “spreading hate against Jews and the West.” They even accused Achille Mbembe of anti-Semitism. Mbembe is a Cameroonian post-colonialist thinker and one of the greatest black philosophers in the world.

After being targeted by Naas – through both street demonstrations organised with Anti-German groups outside exhibitions venues and multiple online posts – I was targeted by members of Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland, or AfD). The AfD is a Fascist-infested far-right party that makes no secret of its hostility to migrants and Muslims. They wrote offensive public statements on me. AfD’s Frank Grobe openly said in the local parliament that they were against artists with Muslim names. And liberal arts establishment did not lift a finger. In Germany, the Right and the fake Left are united by their hatred of anti-Zionist communities, with media acting as a sounding-board.

Many from the Jewish community who are sympathetic to the Palestinian cause stood with me. The police prosecuted and beat up many Jewish artists such as Yuval Carasso and Adam Broomberg. The very first person to show me solidarity was the Jewish performance artist Oriana Fox. She always invites me to her family home for Hanukkah.

You see, in Britain, they teach us that after World War II, the Nazis fled Germany. But I think they actually became embedded in the country’s social fabric. It is my opinion that West Germany was never properly de-nazified. This, we could say, is the core of the problem. It didn’t begin with Documenta. And it certainly doesn’t end with Documenta. Nor does it concern Germany alone: state repression knows no border…

What does the future hold for you? Are there any new projects you can tease us with?

In November, I am going to Peru to present Shy Radicals. In 2023, Caja Negra translated the book into Spanish. Since its publication, it has enjoyed unparalleled popularity in South America. Now I am working on my second book with Book Works. It’s titled Radical Chicken, and it draws on my ongoing Fried Chicken project. I am making new zines. Recently, I have started making zines in German, as I’ve been attending the Goethe Institut. The first one I made is titled My German Language Exam is Tomorrow.

And of course, I will continue to raise my voice against all forms of oppression and injustice. I am currently very deeply involved in the wave of pro-Palestine demonstrations sweeping college campuses across Europe and the US. As an alumnus, I’m working with the University of the Arts. We organise events to raise awareness about the ongoing plight of the Palestinian people, build solidarity and draw attention to state violence and repression.

Despite advocating for decolonisation and intersectionality, art institutions are still very much plagued by racism, exclusionary views and complicity with Apartheid, war crimes and genocides. As an artist, curator and activist, I will continue to push back against all forms of gatekeeping and discrimination. In the art world and beyond. Another art world is possible, and the collective action for Palestine liberation leads the way forward.

My Brother is Back, curated by Hamja Ahsan, is on display at WIP Space Studios, London, until 8th September.

For further information about the show go here

For further information about Hamja Ahsan go here

To support Hamja go to gofundme.com

Interview Jacopo Nuvolari

Featured image: a still from the Shy Radicals movie, directed by Tom Dream