Antonia Campbell-Hughes has never been easy to pin down. Actor, writer, director, and one-time fashion designer, her career has moved fluidly between disciplines while always circling the same themes: identity, fragility, and what it means to be human. After years spent on screen in films like 3096 Days and Cordelia, and celebrated turns on television in Dangerous Liaisons and Black Doves, she made her directorial debut with It Is In Us All, a striking, atmospheric piece that earned the SXSW Extraordinary Cinematic Vision Award. Now she is preparing to shoot her second feature, Diamond Shitter, a visceral thriller set in Geneva’s expat community, with a cast that includes Raffey Cassidy, Eva Green, Ben Whishaw, and Alessandro Nivola.

We sat down to talk about her fascinating and varied career, holding herself to the standard of writing scripts that could stand as literature in their own right, the brutal training ground of fashion, and the freedom of telling stories beyond gendered expectation.

What are you currently working on? What projects are you especially focused on at the moment?

I’m just about to start shooting my second feature, Diamond Shitter. I was predominantly an actor for about 18 years, but I’ve been writing professionally since I started acting. My first feature came out in 2022, and this new one has had a longer road in production because it’s a much bigger film. We’re due to shoot in Q3 this year – autumn or winter.

What is it about? What can you tell us about it?

It’s inherently about value, in the broadest sense. I first wrote a version of it back in 2012, developing it with Screen Ireland, but then I took a hiatus to focus on acting. After making my first feature, I re-embraced the script, which was then developed with the BFI.

It’s set in Geneva, where I grew up. The top-line narrative follows a young Irish woman who goes to work at the UN and is confronted with the wealth and grandeur there – and everything that lies beneath. It explores social status, gender, and other man-made measures of value, and asks what value truly is when you strip those away.

I was very influenced as a teenager by Bill McKibben’s climate writings, particularly his predictions about the impact of excess wealth on the climate. But if you talk about climate when pitching a film, you don’t get very far. So it’s a thriller, with deeper thematic parallels and long-reaching tentacles. Films take a long time to gestate, and this one has become even more prescient over time. We’re living in a period of global fatigue, where events are unpredictable, people have to roll with the punches, and there’s a strong yearning for direction and justice.

The film follows a young person on a journey of discovery, and the ripple effect that has on those around her, leading them all to feel more grounded and fulfilled. That’s a roundabout way of explaining it, but I think those ideas are vital right now, when everything feels so uncertain.

It’s not even about hiding activism under a more commercial story. The works that have stayed with me are those with enough nuance to have a lasting impact. We’re in a time of immediacy, where people want shortcuts, and I find that disappointing. I grew up believing in graft – digging a hole, putting in the work – because of the fulfilment that comes from it. In a very immediate landscape, that’s what’s going to give cinema lasting power.

Your first film, It Is In Us All has been described as striking and atmospheric. What inspired the story, and what led you to direct it?

I’d won a Screen Ireland micro-budget award, and your debut is the one place where you can be completely self-indulgent creatively. It was a small budget, so there wasn’t the pressure to deliver a financial return. Around a thousand people applied, 12 were shortlisted, those were developed down to six, and then to three.

Everything I write is in some way a version of my own personal story. The protagonist, Hamish, played by Cosmo Jarvis, is a version of both myself and my father. At the time, I was also interested in using the platform of a women’s fund to write about men, to explore and observe masculinity.

I’d been spending a lot of time in Donegal, where I was born but left at the age of two. As an adult, I chose to return and get to know it – my heritage land – but I always felt I couldn’t be nationalistic because I wasn’t truly of it. My father was English, and he loved the place with the perspective of an outsider, as I do.

While there, I noticed an ongoing pattern of very young teenagers, sometimes as young as 12, driving cars at high speed and having fatal collisions. These kids were nothing like those I’d seen in London or other big cities – they were almost like Lord of the Flies: visceral, vital, and passionate. The driving wasn’t malicious, it was tribal.

I contrasted that with men I knew in London who had the best jobs, the best clothes, everything external – but nothing internal, like a husk of a male. I wanted to create a story where those two types of energy collided through a traumatic event, and the protagonist, through that impact, begins to observe what it truly means to be alive. The film grew out of a mix of those observations and personal experiences.

Do you find, as the director, that a film feels more like your baby than when you’re writing or acting? Would you describe yourself as an auteur in the way you direct?

I actually see myself more as a filmmaker than a director. For me it’s about executing a concept, whether that’s through the written word, performance, or the visual landscape. That hybrid – taking something from the page into pace, place, and space – is where I feel most at home.

Filmmaking, to me, is a sensory architecture. I’m very passionate about the visual landscape, and I like to construct films so they feel like a curated, multi-layered experience. It’s not improvisational – everything is very considered. The power of cinema is in what images and sound can deliver together, sometimes more profoundly than words on a page. A quiver of skin, a silence, a vast landscape – those can communicate more than dialogue ever could.

That’s why I care so much about the distinction between filmmaker and director. A director can be extraordinary, but for me it’s about pulling all the components together to create that lasting emotional impact.

What drew you to directing as a form of storytelling, and how does it differ from your experience as an actor or a writer?

My first acting job happened to be comedy, which led to more comedy work. At the time I didn’t appreciate it – I was young and drawn more to European cinema. But comedy taught me to write, because of its collaborative and improvisational nature. That always stayed with me.

Screen Ireland supported me as I moved towards dramatic writing, and eventually asked if I was interested in directing. At first I thought, why should I consider myself a director? It felt like a completely different world. But I realised I should learn the craft properly. On every set I studied what the gaffers, grips, and cinematographers were doing, so I could speak the language. I made shorts to build up layers of learning, and when I finally directed my feature, I knew what I was doing.

Some people can just switch sides of the camera and direct, but I wanted to approach it with respect. For me, it was a long journey, but a necessary one.

What tends to come first when you’re developing a film – a concept, images, characters, themes, or something else?

Writing is always at the core for me. I love the craft of it, even though it’s daunting and difficult. I put a huge amount of work into making a script feel excellent, something that could stand alone as a written piece.

There are constant themes I return to, often around my confusion with the human condition – the disconnects, the way we operate. Film gives me a space to explore that and to communicate it. And because making a film involves so much labour, time, and money, I feel a responsibility to deliver something that really repays everyone’s effort. The writing is always the first port of call for me.

Sequin sleeveless mini dress Marques’ Almeida Puffed extra long sheer sleeves with ribbons Dreaming Eli Sandy dress (worn under sequin dress) Critter Spotted Tights Emilio Cavillini Boots ROKER

White Silk Dress Sanna Patrick Black Jersey gown (worn underneath) Critter

Could you imagine giving your writing to somebody else to direct?

Not right now, though I know I’ll get there eventually. It’s the next stage, in a way. A script in another person’s hands always becomes something different, and that’s part of the discipline – many writers are writers and many directors are directors.

For me, being the author means I can execute the work myself, though of course there’s always compromise, because film is such a collaborative medium. I like working with people I admire, so I can give them a platform for their talents and have them shine as part of the bigger picture.

As an actor, I always believed it was my job to serve the director’s vision, no matter their method. That taught me to be malleable, but filmmaking feels very different – it’s a process that’s all in your head, while acting is about openness and being constantly accessible.

You often write male protagonists who explore vulnerability in ways we don’t usually see on screen. What draws you to that perspective?

It’s something that came quite organically. Maybe I just lean slightly more towards that spectrum myself, but I’ve always wanted to go deeper into the male emotional landscape, which is often only handled on the surface. With my next film, I’ve shifted focus. The protagonist was originally written as gender non-conforming – not in the sense of choosing a non-binary identity, but as someone neutral, untouched by societal expectations of gender. The story isn’t about pronouns or politics, but about depicting a human being who exists outside those constructs. For that reason, I deliberately avoided casting choices that might shift the narrative into a debate about identity, because the film is about neutrality rather than a statement on gender.

You starred in 3096 Days, which told the story of Natascha Kampusch’s abduction and imprisonment, how did you prepare for such an intense role, and what were the biggest challenges of portraying someone who went through that experience?

That film is like the gift that keeps on giving – it was so long ago, yet I can walk into a supermarket anywhere and people still know it. I never understood the obsession with a girl in a basement, but people are drawn to true crime. At first, what interested me was the chance to work in another language – it was meant to shoot in German, and I wanted the challenge of speaking with native-level fluency. On top of that, Michael Ballhaus was shooting it, which was extraordinary.

I actually turned it down initially because I was afraid of the weight of the story. I’m not a method actor, but I do like to find the emotional core of a person, and I wasn’t sure how to approach it without being swallowed by the trauma. Then I saw an interview with Natascha Kampusch, and what struck me was her clarity. She compared her experience to women who are beaten by their husbands and still make them dinner every night – she had such insight into her own survival. That reframed it for me, because the script focused on the relationship at the heart of the story rather than just the sensational aspect.

It’s funny, I’ve made lots of films, but that one never seems to go away. And it makes me think about how acting and directing intersect. When you’re directing, you’re almost locked out of acting opportunities for years at a time – it’s very hard to balance both. There are people like Jodie Foster or Kevin Costner who’ve managed that longevity, but it’s rare. I always admired filmmakers from the early mumblecore collective, like Amy Seimetz and Kate Lyn Shiel, who managed to carve that dual path. It’s still something I think about, how those two sides of me fit together.

Do you think that your background in fashion shapes your approach to filmmaking or performance?

I think they’re the same, and that’s only something I’ve realised now. When I was young, I didn’t consider what I was doing to be fashion. I thought I was designing – creating three-dimensional, conceptual constructs. Looking back twenty years later, I can see the same voice, the same language, running through both my fashion work and my films.

Fashion is brutal, though. As a teenager I was travelling constantly, producing four collections a year, running a business, and suddenly having to reconcile art with commerce. I believed it was art, but I quickly learnt the reality. That was the hardest work I’ve ever done, and it was an incredible training ground.

My idols were inventors – people like Hussein Chalayan, who I considered a filmmaker in the broadest sense. That’s what inspires me: invention across mediums. Actors, designers, directors – they’re all inventors at heart.

Do you see yourself as an inventor?

In a way, yes. I’m endlessly curious, which can be exhausting, but it drives me. I don’t think scale matters – what matters is curiosity and exploration. I’ve always been drawn to philosophy and theory of knowledge, those ways of questioning and critiquing. At their core, inventors are people who probe, discover, and create, and that’s what I strive to do.

You’ve lived in Ireland, England, Germany, Switzerland, and the US. Do you feel that moving between those places has influenced your sense of identity and voice?

Yes. Of course everyone’s upbringing shapes them, but for me it’s a mixed bag. I’m obviously very privileged in terms of access and experience, with a broader knowledge of cultures and people. What’s funny is that the film I’m making now, Diamond Shitter, is specifically about value, and one of the things I wanted to explore was a place that doesn’t have class or even an understanding of it. That comes directly from my upbringing.

I spent most of my childhood in an expat community, going to international schools. It was incredibly multicultural – in my kindergarten I was the only white child – and it was very transient, with people moving in and out all the time. There was extreme wealth and people with very little, but everyone presented in the same uniform way, the expat type. So I grew up essentially class-blind. I had no concept of it.

When I moved to Ireland at 16, suddenly I had to learn this new language of class, almost like learning to interpret regional accents – knowing where someone is from and instantly understanding their demographic. It was completely new for me, and it made me very interested in those codes, the ways we judge or align ourselves in society.

That blindness can be a privilege, because you’re not instantly forming judgments when you meet someone. But at the same time, people find comfort in belonging – in family, nationality, football allegiances, all these Russian-doll layers of identity. When you take that away, you’re left with something more fragile. So that’s what my upbringing gave me: a way of seeing things in their immediacy, but also a deep craving for heritage, history, and family.

What have you noticed about the landscape for women moving from acting into directing? Has anything shifted in recent years?

Yes and no. I think there’ve always been actors who’ve become filmmakers that I’ve admired. Asia Argento, for example – Dario Argento’s daughter – she’s always been very political, and she adapted The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things, the JT LeRoy novel. There’s Amy Seimetz, French filmmakers I admire… so it’s always been there.

What feels different is the scale. Phoebe Waller-Bridge, Emerald Fennell – those kinds of figures created huge commercial successes, and suddenly strong female voices were stepping into the studio space that men had long dominated. That shift matters, even though the numbers are still not great.

I think you have to separate filmmaking itself from the commercial studio system. In independent and European cinema, extraordinary work has always been there. But then, for instance, in France there’s still an ongoing battle. They didn’t have gender parity in funding, and filmmakers like Julia Ducournau and others had to come together and form an active movement in 2021 to fight for equal opportunities. Since then there’s been a conscious effort to balance funding and placement.

And I think it’s good that people are experimenting with ways to make things more equal. But it’s also delicate. Awards bodies are moving to abolish gendered categories, but some people really want to keep them, just as in sport. It’s not a simple question.

You mention awards bodies moving to abolish gendered categories. How do you feel about that shift, and about the way people still try to read gender into filmmaking itself?

One of the best compliments I’ve ever received came from a Berlinale programmer called Andreas Struck, who was on the panel for the European Film Promotion when I was named one of the top ten UK female directors of 2022. His work focuses on films by women directors, and he told me mine was the only film he’d ever seen where he couldn’t spot the gender of the filmmaker. For me, that was the greatest compliment, because I want my work to be present as a human effort rather than skewed by anything personal.

I grew up very much as ‘Tony the boy’. I was in the boys’ baseball team, I was in the Scouts. It wasn’t conscious, it was just natural. Later, at around 12, I felt the need to fit in more, so I’d wear a shirt with a pink cuff or something. Then I got into punk, shaved my head, and again I was very gender ambiguous. That came from my creative influences, not as a statement.

It was only when I started acting that I was told to conform, to present a certain way. At that time, actors were expected to be blank canvases. Now it’s different, and I think it’s great that actors can have identities and voices around their own leanings. But when I started, it was all about having long brown hair, looking nice, and fitting an image. Acting is a bigger job than just acting – you’re expected to be an ambassador, a spokesperson, and that pressure can be difficult.

What’s a strange or unexpected thing you’ve had to Google for research?

For my first film there’s a scene where a character has a compound fracture. I wanted him to reset it, seal it, and fix it himself, so I fully researched how that could be done – with super glue, masking it, all that. My advice is: don’t Google image ‘compound fracture’.

There have been worse things, but I’ve also been labelled as working in body horror. I don’t see it that way. For me it’s about body degradation as an immediate portal for the audience to connect on a deep level. Showing physical vulnerability with complete accuracy is something I love to explore. But it does mean I end up going down some very dark research rabbit holes.

What’s something you’re secretly brilliant at that nobody ever asks you about?

I can predict the future.

Last week in New York there was a traumatic incident, and I saw it before it happened. I don’t mean that in a mystical way – I’m not spiritual – but I’m fascinated by physics and quantum theory, and I think energy has a before and after. My father was a pure science buff, so I think of it as the science of spirituality.

But, yes: I can predict the future.

Wow – amazing answer!

I don’t have your gift for foresight, but I’m certain we’ll be hearing much more about your work in the years ahead.

It’s been an utter delight speaking with you.

Antonia Campbell-Hughes’s second feature, Diamond Shitter, begins filming later this year with a cast including Raffey Cassidy, Eva Green, Ben Whishaw, and Alessandro Nivola.

She can also be seen in Netflix’s Black Doves and Lionsgate/Starz’s Dangerous Liaisons.

Interview by Nick Barr

Photographer Jemima Marriott

Stylist Jo Shippen

Makeup Lucy Wearing

Hair stylist Jon Chapman using Oribe

Photographer’s assistant Lee Furnival

Stylist Assistant Emilia Zentner

Top image credit

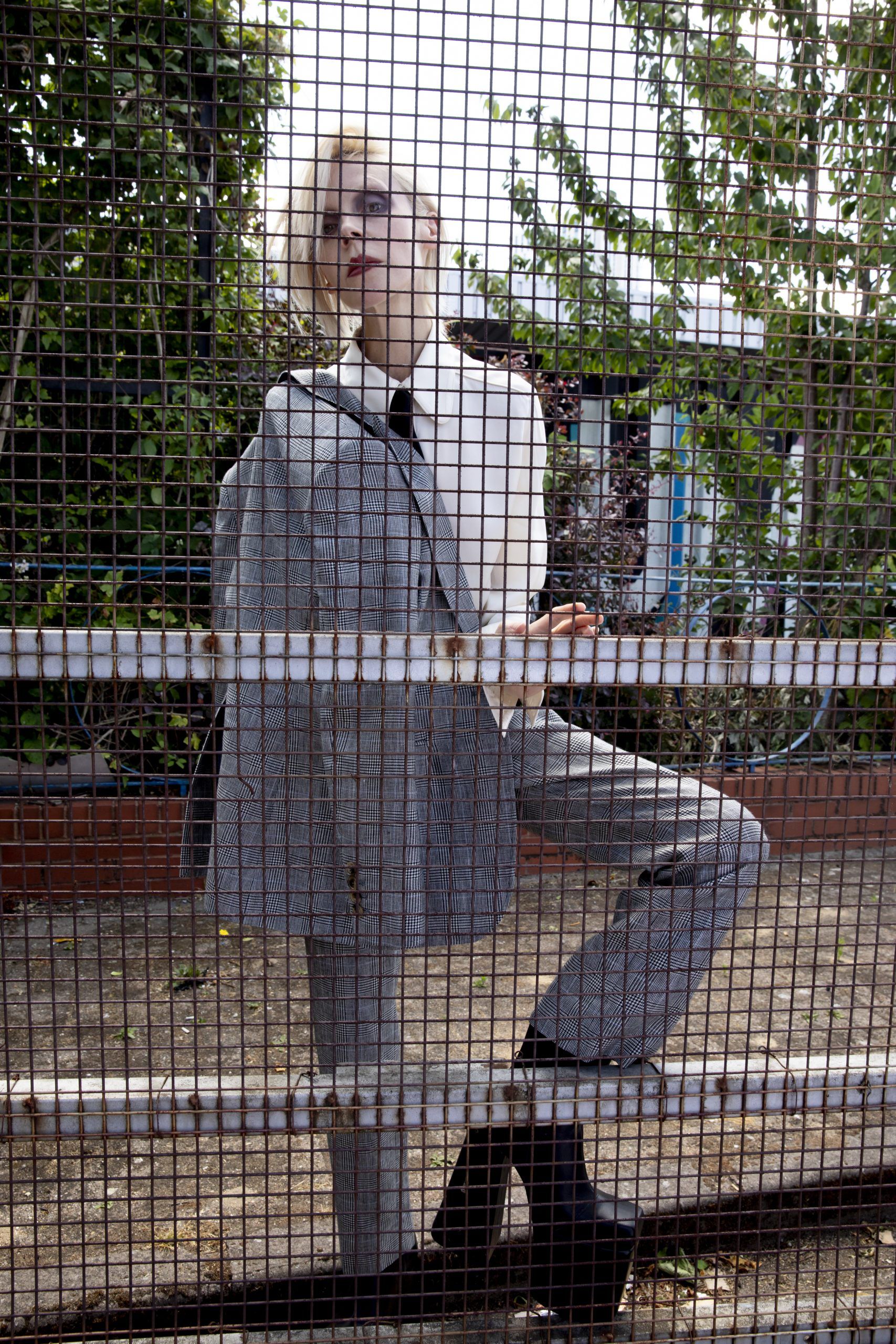

Earl Jacket and School boy trousers Bella Freud

Silk Minnelli shirt with silk bow tie Bella Freud