A trailblazer in the world of street art, Lady Pink has been making her mark on the international graffiti scene for some four decades. A new exhibition titled Miss Subway NYC – at D’Stassi Art, London, until late September – pays homage to the “Grande Dame of Graffiti” by offering a vivid and compelling look at her rich and distinctive oeuvre.

Born Sandra Fabara in Ecuador in 1964 and raised in Queens, New York, Pink was drawn to art at an early age. At 15, she began cutting her teeth in tagging and bombing, making her debut on what was then an almost exclusively male-dominated underground scene as one of the very first women street artists. In 1981, at 17, she was featured in MoMA PS1’s seminal show, New York/New Wave, along with the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring.

A year later, she landed a starring role in the film Wild Style, garnering something of a cult-figure status among hip-hop enthusiasts. After becoming involved in New York City’s buzzing gallery scene, at the age of 21, Pink was given her first solo exhibition, Femmes Fatales. Held at the Moore College of Art, the show helped cement the artist’s status as a fearless voice reshaping representation and challenging sexism within the graffiti culture.

With her work included in prestigious collections such as those of the Whitney Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Groningen Museum of Holland, Lady Pink is now a well-established household name both within and beyond the street art community of New York. True to her reputation as an outspoken gender equality advocate weaving artistic expression with a commitment to social causes, Pink today divides her time between mentoring young female artists and holding community workshops, as well as continuing to produce new work to be showcased in exhibitions in the US and abroad.

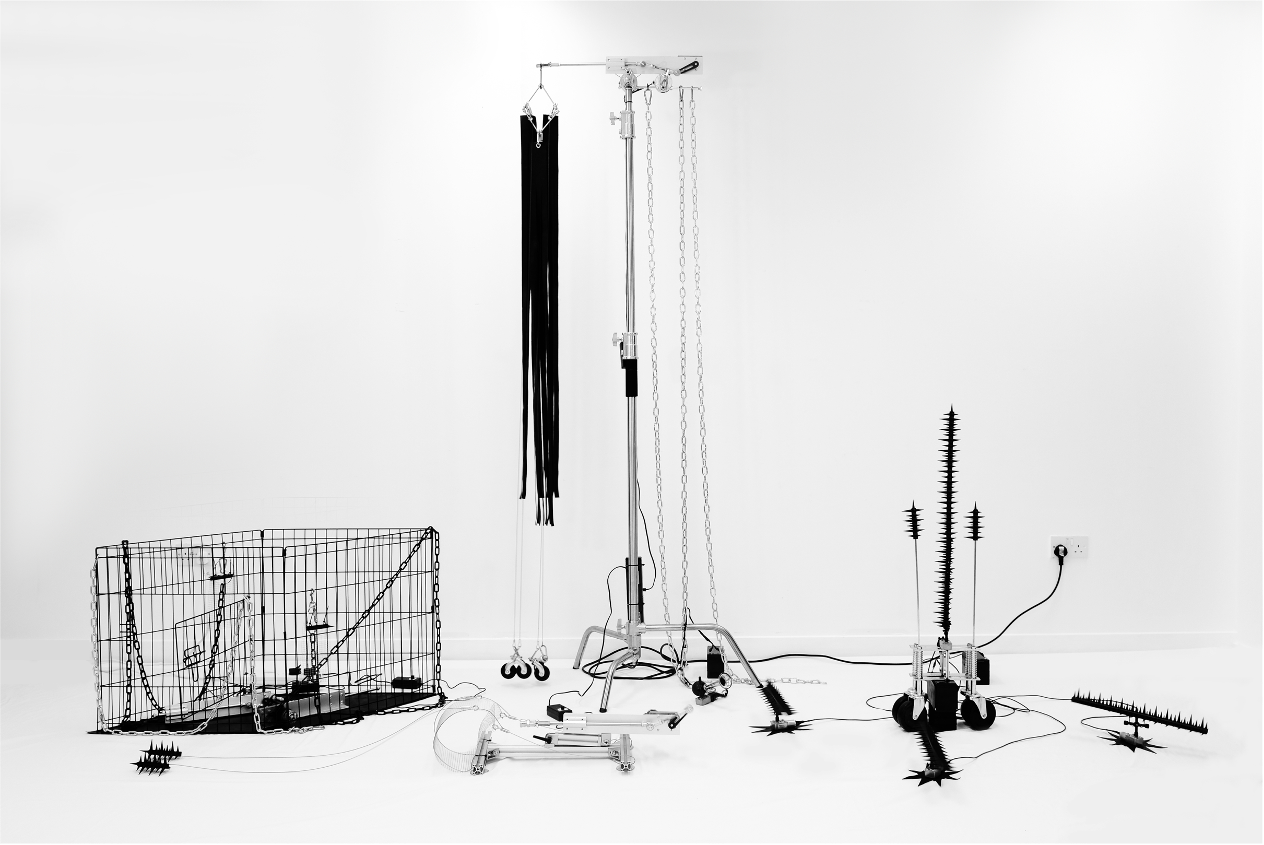

With a selection of original works by the artist, including new commissions and archival pieces, sketches, and ephemera, Miss Subway NYC traces Lady Pink’s journey from her early days to her current standing in the art world. Drawing inspiration from the long-running New York beauty pageant Miss Subways, the exhibition offers the viewer a truly immersive experience into Pink’s world with a full-scale recreation, inside the gallery, of a graffiti-covered NYC subway station – the classroom, one might say, where Sandra Fabara first learned the ropes of her trade.

1883 Arts Editor caught up with Lady Pink for a chat about street art, female agency, and how the public’s and the art world’s perceptions of graffiti have shifted over the years.

Hello, thank you for finding time for 1883 Magazine! Can you tell us about yourself? When did you first start making graffiti and how did you get into it?

I live and work as an artist in New York. I started out as a graffiti artist when I was 15. The police arrested my first boyfriend for writing graffiti and sent him to live in Puerto Rico. I felt that loss deeply. Out of grief, I began tagging his name around my middle school. By the time I went to high school, friends helped me evolve the tag into a new name — one that was mine. That’s how it all started.

What was the graffiti scene in New York like when you first started?

When I entered the scene in 1979, graffiti had already been around for a decade. There was a strong subculture, with its own hierarchy, ethics, and legends. It was underground and gnarly — you couldn’t just walk into train yards without belonging to the right crew. It was almost like joining a guild. The boys didn’t want to take me seriously at first. But eventually I proved myself by painting all night long and showing I was fearless.

The graffiti scene has always been a bit of a boys’ club. What challenges did you face as a young female artist trying to make it in a male-dominated field?

It was tough to be taken seriously. The guys assumed I was just another pretty girl in dresses and makeup — which, as a Latina, was part of how I presented. However, inside I was a tomboy. Once I proved I could hold my own with elaborate pieces and long nights, I gained respect. Being female also worked in my favour at times. The boys liked having me around, and with the feminist movement in the air, they wanted to be inclusive. When I was just 16, curators invited me to exhibit in the first graffiti gallery show at Fashion Moda in 1980, alongside some of the top male artists of the time.

Can you tell us about Miss Subway NYC at D’Stassi Art? What can we expect to see in the show?

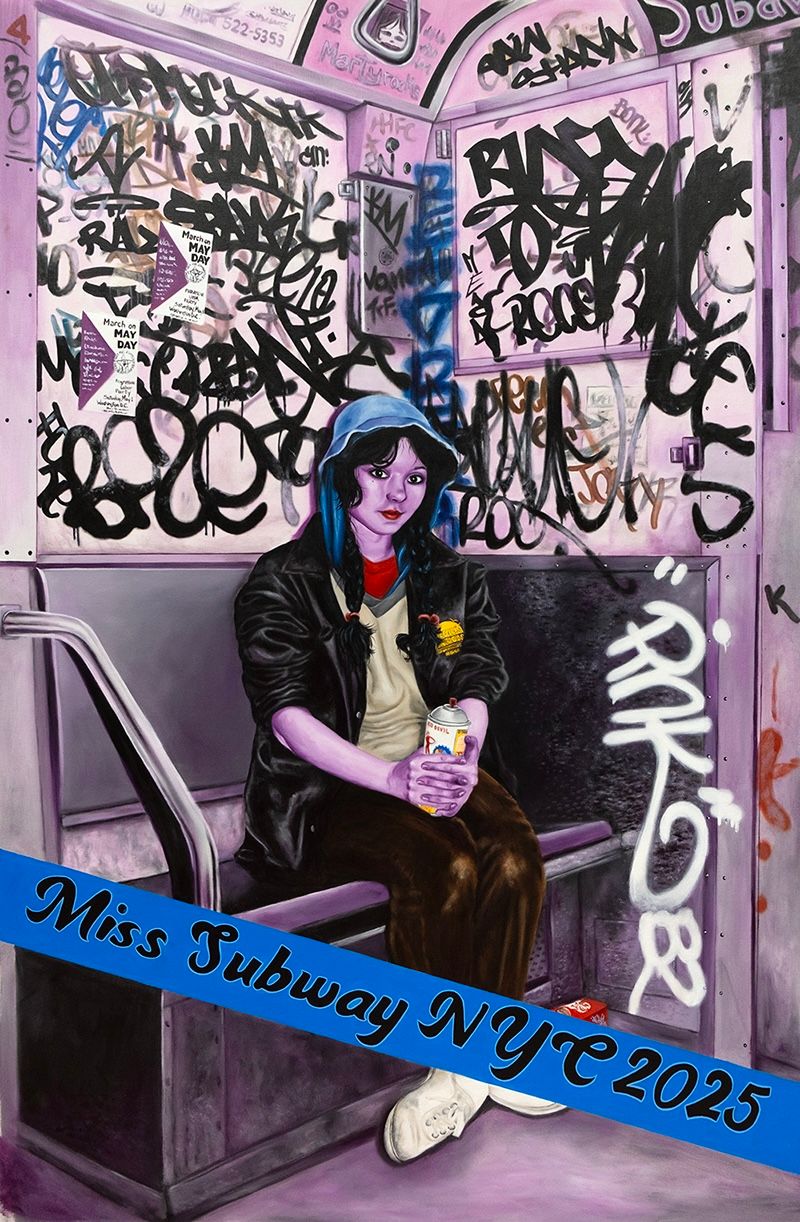

The title comes from an old New York beauty contest. It ran in the subways during the 1940s and 50s, ending in the mid-70s. Organisers recently revived it in a more camp, inclusive way. For this show, I revisited the iconic Martha Cooper photograph. The one of me sitting on a subway car, spray can in hand, surrounded by layers of tags. I painted that portrait myself in pinks and purples, while my husband meticulously reproduced the graffiti behind me.

At the gallery, we built a full-scale subway installation — a wooden train you can step inside. At the opening, I tagged it and handed the marker on, inviting others to add their own stickers, doodles, and tags. It became a collaborative canvas, even attracting some of London’s best graffiti writers to join in.

Themes of womanhood and female agency are central to your work. How, in your view, can today’s street art help provide a visual platform for female empowerment and self-assertion?

Absolutely — but not just for women. It takes real courage to put work out in public, where people have no filters. In galleries, responses are polite. On the street, people will tell you to your face if they think your work is trash. That fearlessness, that testing of yourself, is powerful. For women, stepping into that space has its own resonance. Street art can be a tool of self-assertion, a way of claiming visibility in a culture that often overlooks us.

As galleries and museums around the world now showcase street art, how have you seen the public’s and the art world’s perceptions of graffiti and, in particular, your work shift and evolve over the years?

I’ve witnessed that shift first-hand. Since the early 80s, graffiti has infiltrated advertising, fashion, and the mainstream art world. Today, people recognise it as contemporary art. And yet they still demonise it when it’s unwelcome. Tagging on someone else’s property is still vandalism. In my day, we stuck to subway trains, which the city finally cleaned up by 1989. Today’s kids work on streets and walls instead. There’s a place for graffiti — freight trains, industrial sites, highways — but people’s homes and places of worship should be off limits.

As a final question, what do you have lined up for the future?

It’s non-stop. I’m heading to St. Louis for Paint Lewis, a massive festival with hundreds of artists painting along a three-mile wall. Last year I painted with 47 women there — an incredible experience, considering when I started I was the only one. I’ve also got a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles poster. And a rooftop commission for a New York fashion show, and a panel talk in Montreal for an exhibition called Queens. There’s always so much going on, which is why I have assistants and a team. I stay overbooked, but that’s the life.

Miss Subway NYC runs until late September at D’Stassi Art, London, for more info visit dstassiart.com

Interview Jacopo Nuvolari

Top image credit

© Lady Pink