Owen McDonnell has quietly built one of the most varied acting careers of any Irish performer of his generation. After breaking through as Jack Driscoll in the acclaimed series Single-Handed, he went on to roles in Killing Eve, Great Expectations, Bad Sisters, and most recently True Detective: Night Country. On stage he has taken on everything from Jez Butterworth’s The Ferryman in the West End to his current project, Conor McPherson’s The Weir, where he appears alongside Brendan Gleeson.

I caught up with McDonnell to talk about the craft that runs through his screen and stage work, the unexpected turns of his career, and why The Weir still feels so vital more than 25 years after its premiere.

You grew up in Galway and trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama. What from those early years still shapes how you work today?

I first got involved in drama through Irish-language work in Galway. I stumbled across it, realised I had a talent for it, and it gave me the fulfilment I never found in sport.

Starting out in a second language made me focus on detail, and that still shapes how I work. My preparation is about asking questions and finding answers in rehearsal. With a play like this, you’re still discovering new answers every day.

Growing up in the west of Ireland in the 80s, the world felt a long way away, so curiosity became important to me. It’s something I try to pass on to my kids – never think you’ve cracked it. Always keep learning. That’s what excites me about this job, working with Conor and the other actors. I’m learning so much from them.

You mentioned it was your second language. Did you grow up speaking Irish?

No, I grew up speaking English, but my schooling was through Irish. In Galway I got involved with Taibhdhearc, the National Irish Language Theatre, touring shows to audiences who all studied the language.

Every summer a lot of kids went to the Gaeltacht, areas where Irish is the first language. You lived with a local family, went to classes, and only spoke Irish. My summer job as a teenager was touring short plays and a band around the colleges. The students were desperate for a break from lessons, so we felt like rock stars in our minibus.

We’d perform plays, then the band would play afterwards. It made the language come alive. Even now, when I work on Irish-language productions, it’s inspiring to see a whole crew – sparks, chippies, camera operators – all speaking Irish. It shows the language still living and breathing in a modern context.

You’ve returned to Irish-language work several times. When you perform in Irish, do you think about the contribution it makes to keeping the language alive?

I’ve done television with TG4, which is always a brilliant chance to reconnect. Living in Hertfordshire, I don’t get much opportunity to speak Irish, so it’s good to brush up, even if I’m rustier after 30 years in England.

The last big project was An Klondike, about men from Connemara caught up in the Yukon gold rush. It was fast, entertaining, and used Irish in the right historical context. Those characters would have spoken the language, so it felt authentic. Too often you see dramas where everyone in the police or hospital speaks Irish or Welsh, which was never true.

For me, the key is quality. If you make something good, people will watch in any language – as we’ve seen with Nordic drama. Irish-language film and television is in a strong place now.

You first made your mark with Single-Handed as Jack Driscoll. What did leading that series teach you about carrying a show?

Everything, because I’d never worked a day in television before that. I’d been out of drama school seven years and only done theatre. I was in a play in Galway when a few of us auditioned in Dublin, and I ended up with the lead.

The director told me: be on time, be prepared, respect everyone, and be brilliant. That advice has stayed with me. The most important thing is respect. Whether it’s makeup, set painters, or camera crew, everyone is working towards the same goal. Being number one on the call sheet doesn’t make you more important.

I’ve been lucky to work with people who share that outlook. Sandra Oh, Sharon Horgan, and Jodie Foster on True Detective all set the tone by talking to the crew and being present.

We filmed True Detective in Iceland, which felt like the west of Ireland on a grand scale: vast empty landscapes, wild weather, epic waterfalls. There is a kinship too, since DNA studies show much of the population has Irish and Scottish roots from Viking times. Growing up on the edge of things, whether in Ireland or Iceland, makes you very aware of identity, and that sense of being slightly apart shapes the work.

Let’s talk Killing Eve. How did you first land the role of Niko, and what attracted you to that character?

I auditioned in the usual way, first with the casting director and then with Phoebe Waller-Bridge. The scripts immediately stood out, and I already knew Jodie Comer and Sandra Oh were outstanding.

Phoebe has a gift for finding humour and pathos in the ordinary, and those first scripts felt extraordinary. With Sandra and Jodie in the mix, it became something very special.

We thought it would be a good job, but none of us realised how big it would become. Sandra came back from the American release saying, ‘This is huge,’ and she was right. By the time it aired here, audiences embraced it. The timing with #MeToo made it resonate even more. Instead of the usual troubled men, it was brilliant, complex women driving the story.

It was life-changing. I started filming three days after my son was born, so that first season is a blur. When you marry an actor you take the rough with the smooth, but I do a lot of childcare when I’m not working, so we balance it out.

Niko has quite a journey through the series, from being the man outside it all to being pulled into chaos. What were the most challenging moments for you to play?

The biggest challenge was getting the relationship with Eve right. Sandra and I talked a lot about it. We saw them as a couple who had been happy, maybe not professionally fulfilled but strong together, until they were suddenly plunged into extreme adversity. We wanted to show how even when you still love someone, a relationship can become irredeemable.

It was also interesting to subvert expectations. A friend once joked I was playing “a really good wife,” which I took as a compliment. In my own life I’m hands-on with the kids and do the cooking, so I could bring that into Niko. It was about making the marriage feel real and recognisable.

The most nerve-wracking moment was being fake-stabbed by Harriet Walter with a pitchfork. She has terrible aim, so it looked like she was really going for it. Niko survives, but that was terrifying.

The books went in a different direction, objectifying Villanelle more, whereas Phoebe and the team empowered both Villanelle and Eve. They were complex and compelling in a richer way.

Your on-screen marriage with Sandra Oh felt very authentic. How did you build that dynamic together?

Sandra loves detail. One challenge of television is the lack of rehearsal time, but she had the confidence to slow things down and make sure it was right before shooting, which actually saved time.

She wanted to get to know my family, and even said, “I’m playing your wife, I’d love to meet your actual wife,” so we arranged that. I know her partner too, and through that we built a genuine relationship off screen as well as on. We would often call the night before to talk through scenes and stay on the same page. Being over here on her own, she enjoyed coming for Sunday dinner and spending time with the kids, which fed back into our work.

What was the biggest thing you took away from the whole Killing Eve experience?

To trust your instincts. The best work doesn’t come from trying to please everyone but from conviction in what the writer is aiming for.

Directors are under pressure, and on a long-running show different people come in for different blocks. Nobody knows your character as well as you do. Sometimes it’s important to pause and say, “Have you thought about this?” Often they’ll agree, because you’ve lived with the character longer.

It’s not about being obstructive. Most of the time you adapt to the shot, but when something feels off you need the confidence to speak up.

Doing theatre reinforces that. At the start of every night it’s just the five of us on stage, completely reliant on one another. You build those blocks, understand why one thing leads to another, and sometimes discover something new weeks into a run. That’s the gift of good writing – it keeps shifting and surprising you.

Actors often say that every night they discover something new in a play, and audiences take different things away each time. Do you find that too?

Completely. The audience educates you. Sometimes you wonder, “Why are they laughing at that?” and then realise it lands differently in front of people.

With Conor McPherson, there are endless levels in the writing. He’s modest and unassuming, but his work keeps revealing new depths. You can watch it on the surface and it works, but the further you go, the more you find.

You recently played Joe Gargery in Great Expectations. What was the key to finding Joe’s goodness without making him feel saintly?

You have to look at the world those people lived in. Life was tough and short, and Dickens often warned against “getting above your station.” I don’t agree with that worldview, but it shaped Joe.

Joe works his whole life to build a blacksmithing business, feels like Pip is his son, and then sees Pip reject it all. That’s heartbreaking. He’s good, but that doesn’t mean he can’t be upset or confused.

People sometimes assume that if you’re from a certain class or place, you have less of an inner life, but everyone does. That’s what you need to capture, not a stereotype.

It’s also harder now to be socially mobile. Theatre wages don’t cover rent in London, so I didn’t start a family until I was 40. In my twenties and thirties I worked bars, call centres, building sites — not careers I wanted, just ways to survive while acting.

It was sheer bloody-mindedness that kept me going. Looking back, I had no money but a good time, and all those jobs gave me life experience to draw on.

On True Detective: Night Country, what did you find different about working on that compared to British or Irish productions?

It was huge. We filmed in Iceland, even studio work in a converted fertiliser factory. The director, Issa López, had written it and was directing. She’s a powerhouse who made everyone feel important.

Jodie Foster, number one on the call sheet, couldn’t have been lovelier. Even during a torture scene she was pulling bits of tape out of my hair, apologising for how humiliating it was. That kind of generosity sets the tone.

Being on the edge of the world, it wasn’t the usual big American machine. Executives flew in, saw the freezing conditions, and left. The rest of us stayed through the winter, with only an hour or two of daylight. We went a bit stir-crazy together, and it fed into the show.

The resources were extraordinary. Five episodes took six or seven months to shoot, compared to a BBC drama’s two weeks per hour. That gave us time to dig in and try things without pressure. To be in that environment, with that calibre of actors, was pretty unreal.

Working opposite Jodie Foster must have been quite something. What did you take away from observing her on set and her process?

She’s completely committed. Although she directs a lot, she was very clear she was there as an actor. She’d make suggestions but always deferred to Issa López.

Her preparation was extraordinary. She knew the script inside out, which gave her the freedom to be adaptable, to shift a scene instantly. That’s something I’ve noticed with the most successful people – they work incredibly hard. Talent and charisma are part of it, but they’re also workhorses.

She treats everyone with respect, which comes from confidence. In her eyes you can see so much going on, completely truthful. That’s something to aspire to – to keep learning, keep working, and aim to do the best job you can.

Do you find that working with actors like Jodie Foster and now Brendan Gleeson elevates your game?

Oh God, yes. The first seven or eight pages of The Weir are just me and Brendan on stage, so you have to take your space. He’s magnetic, so the audience must believe both characters belong there.

My character owns the bar, Brendan’s is a punter, so you forget you’re opposite a hero and focus on the job. Brendan is incredibly generous in rehearsal. It’s never about how he looks, it’s always about what the story needs. That collaboration is extraordinary.

How has working with Brendan Gleeson influenced your performance?

It comes back to generosity. Brendan and Conor give us the freedom to have our moments and explore the relationships. The three bachelors probably know each other better than anyone else, and that dynamic is crucial.

Brendan is always ready to laugh and enjoy it, and that reminds you to enjoy it too. He layers detail upon detail, which is inspiring. He also creates space to make mistakes in rehearsal, which is what rehearsal is for – not to be perfect but to learn.

The play has such an intimate feel, like you’re eavesdropping in a pub. How do you create that atmosphere of casual storytelling while still holding a big audience in a theatre?

The set that Rae Smith has designed invites people in, but it also comes from us being comfortable in the space. If we’re at ease, the audience is too. It’s one continuous scene – it starts, and an hour and forty minutes later it ends, and hopefully people leave changed.

In Ireland, the curtain goes up and people think, “I know where we are,” but that comes with preconceptions. We subvert that by showing the richness of these lives. Just because someone has a country accent or little money doesn’t mean they lack depth.

Conor sets up expectations then shifts them, building tension and breaking it with humour. There’s ebb and flow, which makes the experience richer.

What makes it work is relatability. Everyone knows people like these characters or sees parts of themselves in them. Loneliness, isolation, missed opportunities – those are universal. The play touches on faith and the supernatural, but ultimately it’s about the people you surround yourself with. They’re your salvation.

And it’s very funny – much funnier than that sounds.

The play first premiered in the late 90s, but it still feels fresh. Why do you think it endures?

For me, it’s about interpersonal relationships and the importance of community. We’re crying out for that now. When it premiered in the 90s, the world was on the cusp of a boom. Since then we’ve had the crash of 2008, the rise of social media and technology, and people are more isolated than ever.

The play isn’t nostalgic for a golden age of community; it’s a reminder that being physically present with people, talking to them, is what matters. Communication and connection are your salvation, not followers and likes. That resonates strongly with audiences today.

Yes, it’s a period piece now – there are ashtrays on the tables, a pay phone in the hallway – but the themes are timeless. Loneliness, control of your own destiny, the hope that comes from having the right people around you. Despite the ghost stories, it’s not really about the supernatural. It’s about people. Even in hopeless situations, there’s the possibility of redemption and happiness if you’re surrounded by the right community.

What kind of response do you hope people walk away from The Weir with?

I think ultimately, it’s a play about hope. You can place your faith in religion, in the supernatural, or in the idea that we’re part of a greater scheme, but those questions can’t really be answered. What the play does show is that if you have good friends, if you’re surrounded by people with generosity of spirit, then your life can have meaning while you’re here.

It’s a small worldview, but a realistic one. There are eight billion people in the world and you can’t interact with most of them. Our day-to-day footprint is small, and there’s nothing wrong with just wanting to get that right.

For me it’s about the quality of your connections. Having a video with a couple of hundred thousand views is not the same as having a meaningful conversation with someone over a pint or a cup of coffee. That’s what really informs the way you live in the world.

You stepped into the lead of Jez Butterworth’s The Ferryman in the West End, already a phenomenon. What was it like joining that production mid-run, and what did it teach you about your stagecraft?

We were lucky because it was nearly a full recast, so we got a proper rehearsal run. Even so, it was daunting. There were twenty-one people in that cast, three and a half hours of theatre, eight shows a week for six months. You quickly learn how interdependent you all are.

What it really taught me was trust. Trust the writer, trust the director, trust yourself. I was picked for a reason, and I had to believe that. At the same time, it reminded me the job is not about me. Audiences are not paying to see my nerves, they have come for the story. Once you commit, you step up and do it to the best of your ability.

It was exhausting, I had a six-month-old baby at the time, but extraordinary. It sparked real debate too, especially among Irish audiences who questioned why an Englishman was writing this story. Sometimes you need an outside eye to untangle complex cultural situations, and the play managed to do that while being hugely entertaining.

In the end it brought me back to why I love the job. I have worked plenty of nights chucking people out of pubs at closing time, so if the choice is between that or finishing a day’s work on stage in front of 1,200 people, I will take the latter every time.

Catch Owen in The Weir at the Harold Pinter Theatre from 12 September to 6 December 2025.

Book your tickets now at haroldpintertheatre.co.uk

Words by Nick Barr.

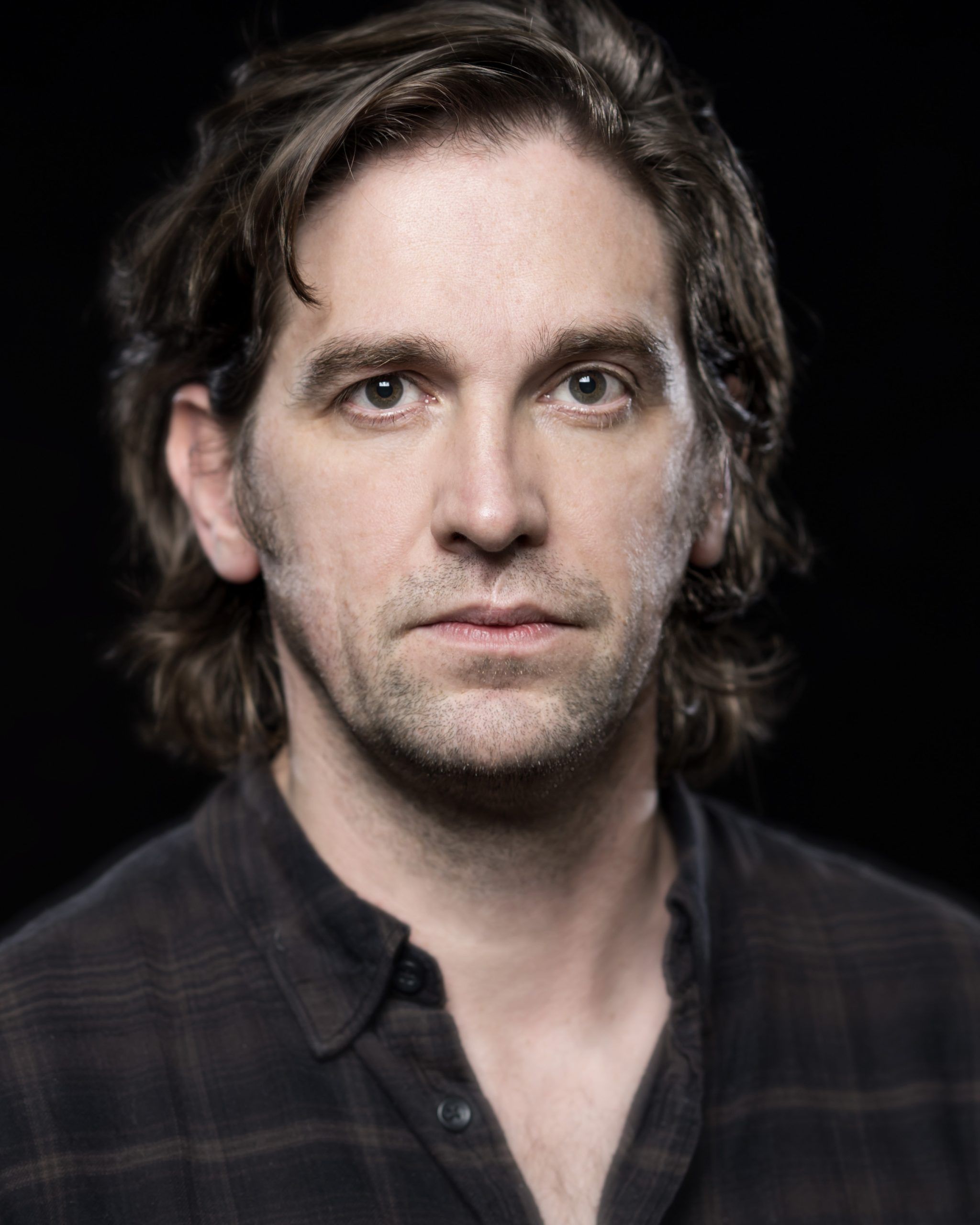

Portrait by Johan Persson

Production photos by Rich Gilligan