Samuel D. Hunter, the American playwright behind The Whale – yes, the one Darren Aronofsky turned into a film with Brendan Fraser, who went on to win the Oscar – has built a career out of finding the big, aching questions of life in the most ordinary places. Diners, Walmarts, small towns that feel left behind. Clarkston, now at the Trafalgar Theatre, is very much in that vein: three people colliding in a small American town, clinging to hope while the walls close in around them.

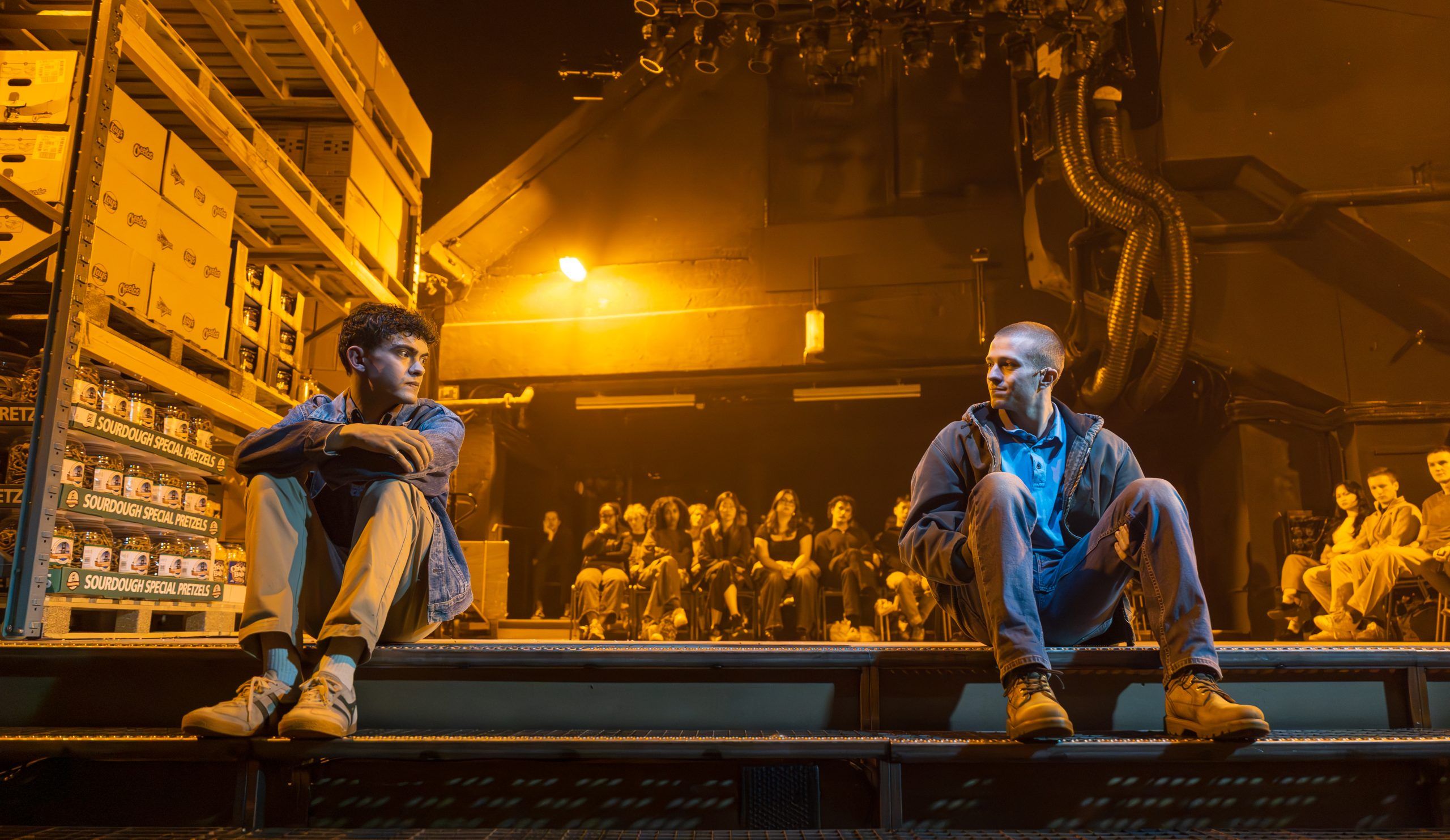

Most of the action plays out in the stockroom of a Costco – not exactly glamorous, but it becomes the crucible for everything that follows. This is where Jake (Joe Locke) has just started working, and where he meets Chris (Ruaridh Mollica). Two young men, breaking down boxes, sizing each other up, circling each other with banter and curiosity. While the set never really changes, dialogue, lighting, and sound expand it outwards – sometimes we’re in a car park, sometimes by the river, sometimes teetering on the edge of something more dramatic.

Joe Locke’s Jake arrives like someone trying to prove he belongs, even though it’s obvious he is ‘not from around here’. He studied ‘postcolonial gender studies’ (a line that gets exactly the laugh it’s meant to), and he drops references to Lewis and Clark as though connecting himself to their diaries and their great expedition will make sense of his own situation. Costco, he insists, feels like the “new frontier.” He’s witty, idealistic, full of sweeping statements – and also living with Huntington’s disease, which is slowly closing the door on his future. Locke captures the humour and the courage, but when the illness takes over – the leg that won’t work, the sense of his body betraying him – it didn’t upset me the way it should. I could see the acting, but I didn’t feel the terror. And I wanted to. I wanted to be moved. I wanted to sit there with a lump in my throat, and instead I was just… observing. Locke is a fantastic actor – his screen work proves it – but here, the raw fear of Huntington’s didn’t hit home.

Chris, on the other hand, was phenomenal. Mollica is magnetic, full of restless energy and sudden bursts of rage. He rolls his eyes at Jake’s big talk, but you can see how badly he wants to connect, how much he wants to trust. His attraction to Jake is messy, complicated, and weighed down by fear – fear of being queer in a small town, fear of letting someone in only to be hurt again. There’s a moment by the river where Jake talks about suicide, dangling his feet over the water, and Chris’s fear is palpable. Later, when Chris reads one of his stories out loud – a piece about grief, about staring your own pain in the face – it’s as if the whole play shifts into something more emotional and open. Jake even says, “It’s like you’ve written all my fears into one story,” and he’s right on a many levels. For me, Mollica brought the real emotion I was craving.

And then there’s Trisha. Sophie Melville plays Chris’s mother as a woman clawing her way back from addiction, desperate to be the mother her son deserves but never sure she can get there. She talks about the 60-hour weeks she worked so Chris could have a ‘normal’ childhood, about the sacrifices that no one seems to remember, about how much she still wants to give. But Chris doesn’t trust her – he’s terrified of watching her spiral again – and that fear runs through every one of their exchanges. Their scenes together are devastating. You can see how much he wants to forgive her, how much she wants to prove herself, and how fragile it all is. Melville is phenomenal. Her pain is so real that at times it’s hard to watch, in the best way.

Jack Serio’s direction is understated and perfectly toned. The world expands subtly: Stacey Derosier’s lighting shifts just enough to transform the stockroom into a riverbank, a car park, the suggestion of something wider. George Dennis’s sound design fills in the rest – the hum of traffic, the splash of water, the buzz and banging of a Costco we never see but can hear just beyond the walls. It means the play never feels trapped, even though the characters very much are.

Hunter’s writing ties these intimate struggles to bigger American myths. Jake can’t stop talking about Lewis and Clark, the original pioneers, as if they can explain his own sense of being lost. Chris clings to his stories as a way out of the suffocation around him. Trisha dreams of redemption but lives with the daily risk of relapse. They’re all searching for meaning, in a world that doesn’t make it easy.

There are times when Jake feels like too much of a victim, wallowing in how much of a “fuckup” he is, and those moments left me cold. I wanted him more empowered, less self-pitying. But the ending pulls it back. For a play so steeped in suicide, addiction, and disease, it doesn’t leave you in despair. The final scene is quietly beautiful, offering a sense of peace that feels earned. I walked out believing that Chris and Jake, broken as they are, might just be okay.

Clarkston isn’t perfect. I wanted to be moved more by Locke than I was. But Mollica and Melville absolutely killed, and the production as a whole lingered with me long after I left the theatre – fragile, painful, but somehow hopeful too.

Clarkston runs at Trafalgar Theatre until 22 November 2025.

Book tickets now at trafalgartheatre.com

Words by Nick Barr

Photos by Marc Brenner