When Jordan Stephens walks into a room, he brings the same restless energy that has defined every chapter of his career. A decade after shaking up British music with Rizzle Kicks, he has written books, fronted mental health campaigns, starred in TV dramas, and appeared in Star Wars and Foundation. Now, he is stepping onto the stage for the first time in Entertaining Mr Sloane at the Young Vic, directed by Nadia Fall.

Joe Orton’s dark, provocative 1960s queer classic is a wild choice for a debut, but Stephens thrives on risk. As he moves from music to acting to writing, he keeps circling the same idea: identity. In our recent chat, he talks about ADHD and focus, masculinity and vulnerability, race and representation, and why embracing chaos can be its own kind of peace.

Nice to meet you, Jordan. How’s your day been? How are rehearsals going?

It’s a whole new world for me, man. I’ve been rehearsing for a month in a little room, but we’ve just moved into the theatre. So suddenly everything changes – the lights, the sound, the space. Things we’ve been practising for weeks get thrown out the window because you can’t light it, or you’re too far away, or you’re facing the wrong way. I didn’t know any of this until yesterday – it’s insane.

That must be a big adjustment. How do you feel it’s going?

Honestly, I think it’s going well. It’s hard to know what people are really thinking – sometimes people tell you nice things, so you don’t meltdown – but my rough guess is I’m not doing badly. Nadia, our director, is incredible. She and I both have ADHD, and I know she’d tell me if there was a problem. She wouldn’t hold back. From the three run-throughs we’ve done so far, I can tell she’s not freaking out, which is good.

I love that honesty. As someone with ADHD myself, I know we don’t always have the same filters – which actually makes it brilliant working with other neurodiverse people.

Exactly. You always know where you stand.

This is your stage debut, which is a huge moment. Had you been much of a theatre person before taking this on?

Not at all. I’ve seen a handful of plays, and I’ve been lucky that most of them were good because they were recommended. But I wouldn’t call myself a theatre person. One of my oldest friend’s dads is an amazing actor – I saw him play Othello once, and that really stuck with me. So to be here now, making my debut on stage, feels pretty surreal.

This is your first stage role, and it’s also Nadia Fall’s first production as artistic director of the Young Vic. How did it feel for her to take that chance on you?

When I was cast in this play, I was a fish caught in a very wide net. I don’t think I was anywhere near the first person people would think of to lead a play at the Young Vic. This was only my third theatre audition ever, even though I’ve been acting for about 11 years.

So, the agreement was: let’s put you in this play. It’s her first production as creative director of the Young Vic, and it’s my first play ever. Let’s not embarrass ourselves. There’s a mutual trust in that. I don’t want to mess it up for her, and she doesn’t want to mess it up for me. And of course, I’m very lucky to be doing it alongside three incredibly experienced actors.

You burst onto the scene with Rizzle Kicks when you were just 19. Looking back now, does it feel like a whirlwind?

Yeah, totally. Our whole world changed in about a month back in 2011. Fern Cotton picked us as Record of the Week out of nowhere – we’d been on BBC Introducing, which was great, but this was different. Radio was really powerful then, pre-streaming, and suddenly we jumped from 144 in the charts to number 8, and we stayed there for a couple of months. At one point, 70% of our sales were physical CDs – that’s surreal to say now.

Life just flipped overnight, and there wasn’t time to adjust. That has its pros and cons. I’ve learned since that music’s a marathon, and in some ways a slow build can be healthier. An explosion is exciting, but it’s also disorientating.

And what about stepping away?

We put Rizzle Kicks on ice on our own terms. There was some tension around the second album not doing as well as the first, but the first had done exceptionally well. The second still sold strongly, but suddenly we were in this rat race with big pop stars and major labels, and that wasn’t what we’d set out to do. Rap wasn’t pop then – it was a strange time.

Harley was struggling with anxiety, I was doing loads of drugs, and it just didn’t feel right. Luckily, we’d already profited as an act, which is rare in music, so the label couldn’t force us into anything. We had control, and we disappeared for nearly a decade. In that time, I’ve leaned into other passions, and I know myself a lot more now.

After stepping away from Rizzle Kicks, you’ve really carved your own creative path – through writing, sobriety, and new projects. What did that rebuilding process look like for you?

It was strange. In a way, I think I went through the same kind of blow-up most people face in their late twenties – it just happened more in the spotlight. Twenty-seven is an age where things change: you might end a relationship, leave the country, change your job. People call it Saturn return, but I’ve always thought of it as a period almost entirely made up of anxiety and confusion.

For me, it was cemented by a really bad, self-inflicted heartbreak. That was the shift. I had to rebuild myself. I went sober, but I lost my confidence and my drive for about a year. I couldn’t even write. Since 2017 I’ve just been learning, reading, building – and realising the paths reveal themselves if you follow them.

I’ve ended up doing things I never thought I could. Most notably, writing a book. If you’d told me back in 2016 or 2017 that I’d write one, I’d never have believed you. I knew I loved lyrics and poetry, but I didn’t think I could write a whole book. And I love it. I really love writing.

I even told my manager five months ago I wanted to focus on my next book – and then two months later I’d done my first documentary and agreed to my first play. It felt like tempting the universe, so I think I’ll keep my mouth shut from now on.

You’ve written a memoir and two children’s books. When you talk about writing now, are you thinking more about another memoir-style book or something else?

People say children’s books are really hard, and writing good ones probably is, but I stumbled into it. I never set out to be a children’s author. Both of my stories are really for adults, just repackaged for kids. They are too short to be a play or a full-length book, so they work as little fables. I have been lucky to collaborate with an incredible illustrator, Beth Susanna.

Those books sustained me in early sobriety. I had pitched an idea to Julia at Waterstones, then disappeared for three years while she kept chasing me. When I went sober and had horrendous writer’s block, I thought, “If I can’t write anything new, I’ll edit what I’ve got.” I sent her a cut-down version of that idea and ended up with a three-book deal from Bloomsbury.

It is mad. I have one book left on that deal. I really love writing, though it is hard. I am not one of those people who sits and writes for hours every day. Friends like Matt Haig do that. At the moment, I am just full of words and sometimes I need to throw them up.

I get that. Especially with ADHD, the idea of sitting down and working for three hours straight is a fantasy.

Exactly.

You’ve spoken about ADHD before. What’s your relationship with focus like these days?

What scares me is realising how much of my hyperfocus gets lost to my phone. In the first week of this play I used a burner because I was nervous about not learning properly or paying attention. During breaks I would just sit, talk to people, stare at a wall, and ideas would come. That used to be me as a kid, just sitting and thinking.

Now I will have an idea, go to note it on my phone, and suddenly I am checking messages or reading about how big Uranus is compared to Jupiter. The thought is gone. The world is not built to suit how our brains work, so we end up building little systems to cope instead of shaping a life that works for us.

You have also been outspoken about mental health in general, especially with #IAMWHOLE. When did you first realise you wanted to use your platform in that way?

It was a complete accident. Trigger Happy TV was making a comeback and I reached out to Dom Joly about a Rizzle Kicks collab. The producer happened to be writing a mental health campaign for the NHS in Brighton, and I had just sent him a song called Whole from a side project I had made with my dad and a mate. He asked if I would use it to help others.

That became #IAMWHOLE, which I ran with Matt Campion at Spirit Studios for six years. I am proud of it. I did not know much about mental health at the start but learned a lot.

I know people complain about self-diagnosis online, but I think it is great when people share their experiences, even if they get it a bit wrong. The only thing I push back on is using mental health to excuse bad behaviour. My book is not about excuses. It is about how ADHD actually shows up in difficult moments.

In 2017 you wrote a Guardian article about toxic masculinity, urging men to open up. Eight years on, do you feel that conversation has moved on?

Yes and no. Feminism has kept moving forward, and there has been real progress around gender conversations, but a new wave of online paranoia has blurred what “toxic masculinity” even means. A lot of young men have grown up surrounded by damaging ideas about manhood, with no context for them.

The anger from women at the time was completely valid, but it is hard to predict where that energy goes. All I know is it is on men, especially as we get older, to be vocal about our choices. Healthier decisions have made my life better, and that is cooler than being a prick with a nice car.

Men need to see that the vacuous path is not worth it. I am hopeful the next generation will handle it better. Millennials grew up in a far more toxic environment, not online but in everyday media. Watch an early Bond film: violence, misogyny, no connection. The fact we can now look back and say “that is rubbish” is progress.

And one thing men can learn from feminism is community, how women hold space for each other and build strength together. We need more of that.

As a mixed-race Black man in Britain, what have you observed about progress – or lack of it – when it comes to representation in the arts and media?

It’s definitely got a lot better as I’ve got older. I know people on the right, especially places like GB News, complain about it and say we’ve gone mad – but the truth is there are a lot of really talented, creative Black people doing amazing things.

Sometimes I don’t think they’re given as much credit as they should be, but the talent and inspiration are there. It’s much better than when I was a kid. Back then, the only people I really remember seeing were Reggie Yates and Angelica Bell. Now there’s a lot more. So yeah, I think it’s in a good state.

People know you mainly as a musician, but you’ve been quietly building a screen acting career for a decade. Was there a moment on a film or TV set when you thought, “Yes, this is something I really want to take seriously”?

Honestly, I just fell into acting, which I know will annoy a few actors, but it is true. I got a wildcard audition for one of Jack Thorne’s early series, Glue. I was basically playing myself, a 20-year-old drug addict, so it came naturally but was still testing. That was when I realised acting is a strange craft. You only have control in the moment someone says “action”. Everything else is out of your hands.

Then came Tucked in 2018. I played a cross-dresser called Faith and loved it. It won a bunch of indie awards and people started saying, “You’re a serious actor now.” So I took it seriously, and then came the heartbreaks. Every time I thought about quitting, another part would appear. I stopped trying to define my relationship with acting.

If I see a bit of myself in a role or it sparks something, I will do it. If everyone around me is on the same wavelength, I am in. That is what makes Mr Sloane fascinating. He is the opposite of everything I believe in as a man, but exploring that shadow self matters. Studying Joe Orton has helped me as a writer too.

I do not think about casting directors or career moves. I just want to do the work and walk away. Along the way there have been wild projects like Star Wars and Foundation. With Foundation I did not even get the audition and still got the call. That was dope.

There are incredible actors out there, and theatre feels like new territory. Spending a month really digging into a character is different. With Mr Sloane, I feel like I know what he is going to say and do, and I love that.

What’s been the biggest change for you moving from screen to stage? You mentioned earlier about facing the wrong way – having to look in a particular direction…

It’s huge. This production’s in the round, so everyone on stage is inside this kind of orb of energy. We’re all part of something shining. The level of acute awareness you have to have about your own contribution to that energy is like nothing you can get in rehearsals for TV.

On stage, even breaking eye contact can shift something. You’ve got to find a way to put the light back in, or hold it. Sometimes it’s shining really bright and you change something – a slight delay before a line, a small movement – and it builds or breaks the feeling. It’s insane. I’ve never experienced that before.

Obviously, Sloane is charming, dangerous, seductive and manipulative. How are you approaching that complexity?

So what I’m trying to do is lean into being approachable. People ask me for directions all the time, even when I’m not in England, it’s bizarre. I know I’ve got an approachable demeanour.

What I’m exploring is how that approachable Jordan can be doing and saying things that are the exact opposite underneath. I’m trying to weaponise that – make the charm itself the instrument of harm. The idea is to let the audience think, ‘Oh, he’s harmless,’ and then watch that expectation get pulled away.

Sloane is accused of being a criminal and ultimately is one. Casting a Black actor in that role inevitably raises questions. Do you think this production is deliberately playing with audiences’ unconscious bias?

I love it. It is important. I am not into this idea that you have to play only “good” characters or worry about what people might think. Forget that shit.

I know what it would have meant to be a mixed-race person in the 60s, let alone a mixed-race criminal or potential sex worker. It was dangerous. But for me, it is hilarious. I am existing in an era where everyone was openly racist, and I am taking the piss. I am robbing people, they are robbing me, we are all trying to get leverage.

It is so Machiavellian that race and class almost become meaningless. It is really just a few human beings trying to survive, and everyone does that. No one is born into a body that is not capable of manipulation or ambition.

The play was considered scandalous in the 60s. Why do you think it still resonates as a queer classic today?

Probably because Joe Orton was writing at a time when he could literally be killed for who he was. His plays were censored, so he found codes and clever ways to express his sexuality under the radar, while poking fun at the people who wanted to look away. That kind of boldness will always be exciting and scandalous.

Society still struggles to be honest about sexuality and desire, which keeps the play provocative. It is pure scandal. Things have changed, but the misogyny is still jarring. Nadia would probably say that showing it honestly is part of the point – and anyway, you will see when you watch it.

How’s it been rehearsing with seasoned actors like Tamzin, Daniel and Christopher?

Unreal. They’re all amazing. Just watching the shifts they make and the choices they bring – especially in tech, when we got into costume, they all just hit another level. It was wild. I thought, “Oh wow, okay. Fuck!” I feel incredibly lucky to be working with them, genuinely. You do find yourself elevating your game – you have to. It really does feel like a dance, with everyone bringing their best so the whole thing rises.

What does success look like to you now compared with when you were topping the charts in your early twenties?

It’s completely different. Success feels much more personal now. I’m really trying not to let external measures dictate it. For me, success is about peace and harmony, whatever form that takes. It’s definitely more internal than it used to be.

And what would you like people to walk away from the play with?

I think it’s so important people understand that every human being has duality. This play heightens that – it’s extreme and absurd at times – but the point is the same. One of my pet hates is when people see themselves as holy or pure. We’re all capable of fuckery, we really are. And that’s something Joe Orton clearly believed and wanted to expose to the world.

Entertaining Mr Sloane is at Young Vic Theatre until 8 November 2025.

Book tickets now at youngvic.org

Catch up on all of Jordan’s news and shows at PlanetJordan

Words by Nick Barr

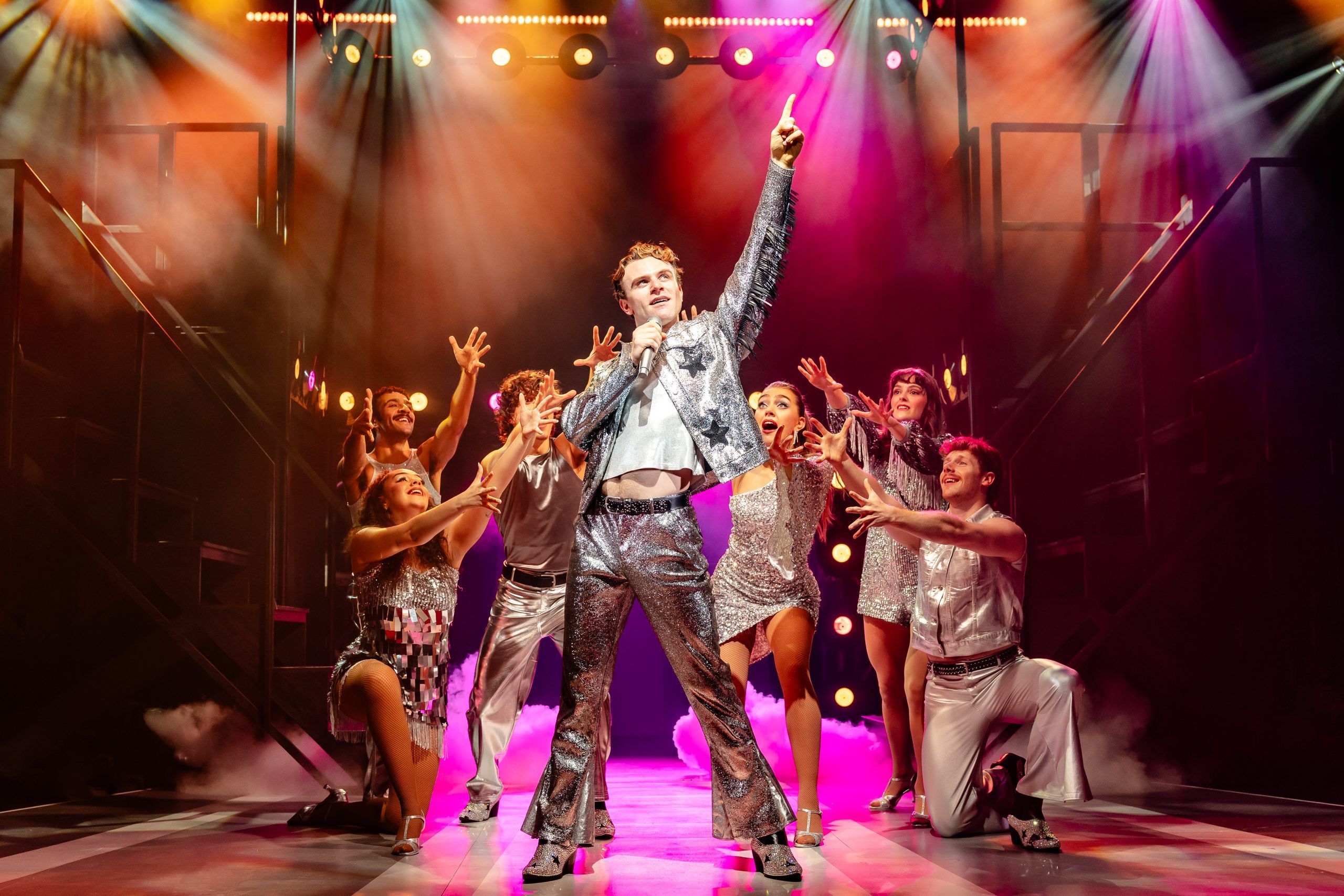

Photography by Ellie Kurttz