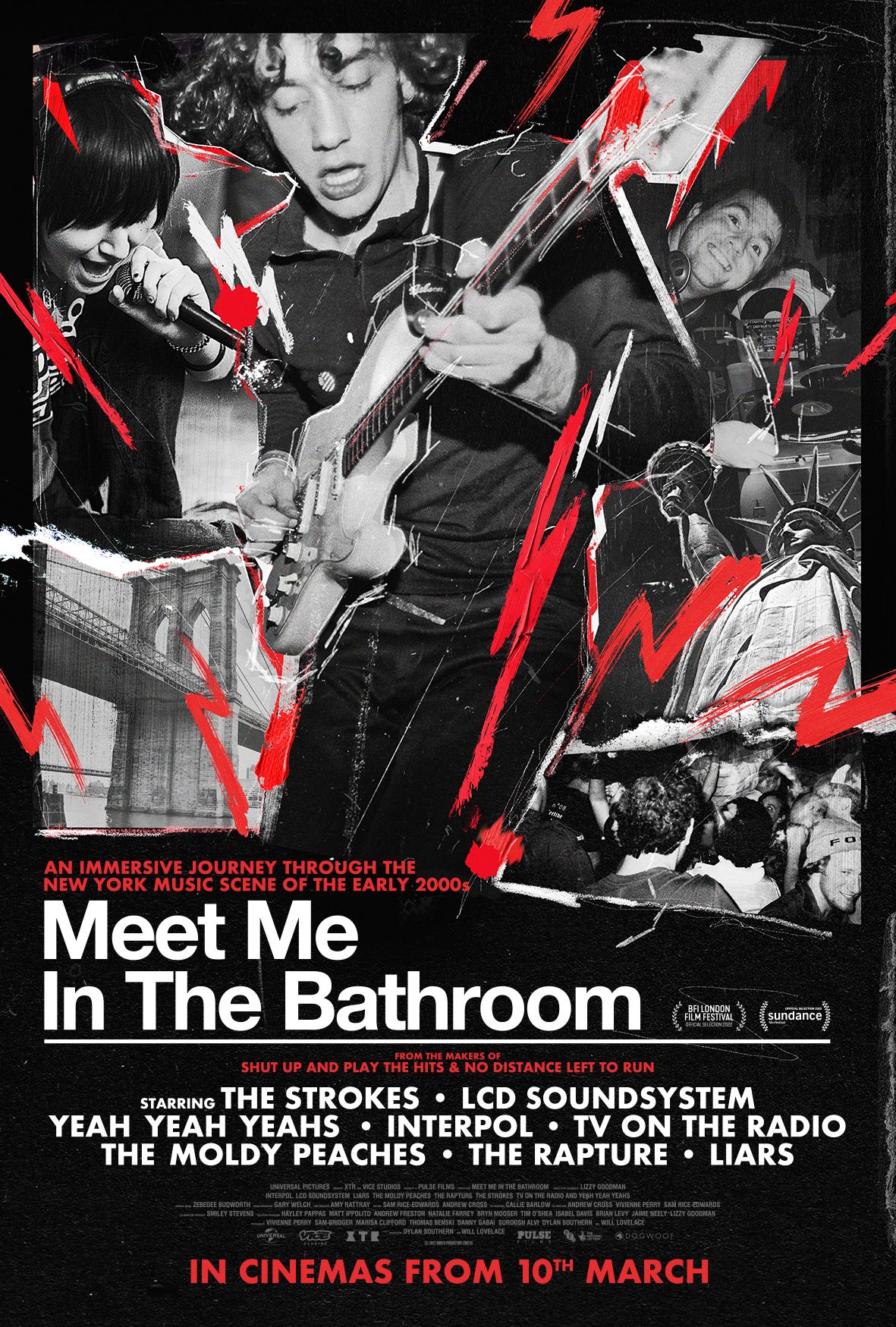

Award-winning filmmakers Dylan Southern & Will Lovelace pull back the curtain on the early 2000’s New York music scene in their new documentary, Meet Me In The Bathroom.

Their career together began with directing the music video for Franz Ferdinand’s Ulysses, and have since gone on to shoot videos for artists such as Bjork, Arctic Monkeys and Idles. Less than a year after their first music video release, the duo made their first music film about British band Blur titled No Distance Left to Run – a Grammy and Grierson nominated success. Their following film about LCD Soundsystem, Shut Up and Play the Hits was sundance selected and regularly appears in lists of ‘The greatest music documentaries of all time’ (Rolling Stone, NME, The Guardian). It’s clear both Southern and Lovelace are bonded through their shared adoration of music, continuing to work collaboratively in exploring both the artist and the environment.

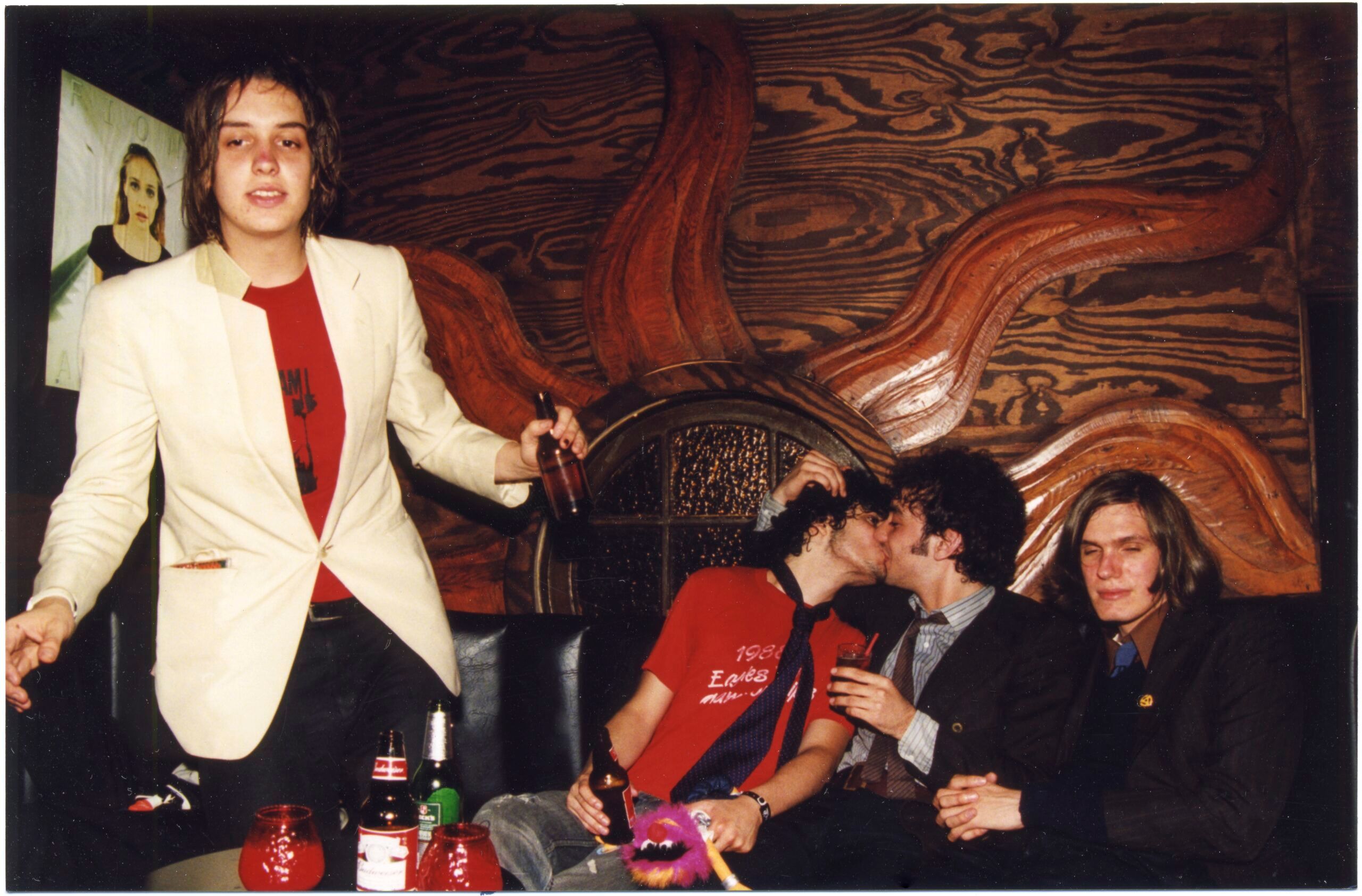

In their upcoming documentary, artists including The Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Interpol, LCD Soundsystem, and more, all feature in never-seen-before footage. With an absence of talking heads, we’re transported with no interruption to the middle of the chaos – the film manages to capture the noise, energy and cigarette smoke of every New York bar willing to let indie music happen. With a vast archive brimming with gritty footage, Meet Me In The Bathroom transports you back to an era of underground chaos and excitement. 1883 magazine sat down with Dylan and Will to discuss noughties nostalgia, unrelenting film archives, and the era of the Minidisc.

So, turning the book into something right for the big screen… did you have a clear vision of what you wanted from the beginning?

Will Lovelace: Yeah, we both read the book and loved the way the form jumps you into a moment. Straight away we thought we’d love to make that into a film but actually, the bit we’re most interested in is the first part of that story. Those first few years when it suddenly starts to explode in terms of new music and new bands, and that to us felt like the most exciting part of it. We always wanted to look at this as a companion piece to the book. The book is brilliant and it’s there if you want to find out more about all those artists, or the ones that came before and after. We wanted to make something that could sit alongside the book, I guess.

Dylan Southern: I think our big thing is we didn’t want to do a talking heads, VH1 style documentary where you see the artists today. We wanted to drop people into that time and that place, and that’s where the notion came that it would be a bit of a time capsule. It would feel fairly intimate, and we would build it entirely from archives that came from the time.

There were so many narratives going on in the film, but it never felt overcrowded or inaccessible – how did you find the editing process?

DS: Torturous [laughs].

WL: Yeah, hard work. It’s a challenge to make a film where you’ve got multiple characters with different story arcs, that was one of the big challenges. Also, an archive of film that you don’t know all the material that you have when you start making it; that was a kind of ongoing process all the way through.

DS: It’s not like you get all the archive and you’re like right, let’s make a film. Archive was coming in right up until the 11th hour. We were discovering stuff during the edit, and so then we had periods of limbo. We wrote the film before we made it and we had an idea of exactly how all the narratives would flow, but COVID hit and kind of dictated that it would be entirely archive. At one point we were going to go to New York and shoot some contextual stuff there. So, you’d have periods where you’re like how are we going to tell this part of the story? and then through detective work you’d end up finding somebody who was at this thing, who knew somebody who had a camera. It was also going on the Wayback Machine and looking at old message boards from the time. Seeing in a photograph a journalists MiniDisc player and going ‘oh, that interview might still exist’. It really was a lot of intense, stressful detective work.

So it was more putting the pieces together like a puzzle opposed to a linear experience?

DS: Yeah, exactly! It was it was a lengthy edit because of that. It was our first time making a documentary in this way, and it was very different to our previous experiences. It was rewarding in some ways, but also you have points where you’re like God, are we going to be able to do this? It’s interesting.

You’ve both made music documentaries in the past – how did it feel shifting from specific artists to a broader period in time for music?

DS: That was the thing that drew us to the project, really. There’s only so many types of story when you’re dealing with music and bands. There’s always the cliched drugs and fall outs and all that kind of stuff. But this one – it was such a specific time, and it was a moment when everything was about to change; technologically, politically, culturally – the world wasn’t going to be the same and nobody knew it at the time. So, the idea of this story taking place in a city which the world’s eyes were about to be on for a very different reason, and at this time when so many aspects of the way we live our lives were about to change… it just felt interesting. It also felt very depressing that it was 20 years ago, because it’s still it seems like yesterday to me. When you started getting the archive through, you’re like Yeah… this was a long time ago! [laughs].

In that sense it must’ve been nostalgic. There are some special moments in that footage. How did it feel seeing it for the first time?

WL: Yeah, that part of it was really exciting. It’s funny, it doesn’t feel like that long ago but when you see the footage shot on analogue format or sometimes early digital, the quality of the recordings feels now like a completely different time. I think that part of it was really interesting! It was pre-internet really taking over, pre-mobile phones. You can see it looking back now that this is the last time that kind of scene, or even that kind of movement would happen in that way.

DS: One of the things I loved about seeing the archive was at that point in the footage, we were starting out as filmmakers and we used to shoot on mini DV tapes, and I remember hating the look of it because it wasn’t film…

WL: Yeah, you’d do anything to make it not look like that!

DS: But now, early digital footage has a feeling of nostalgia in the way that Super Eight did back then. it’s kind of weird how even the aesthetic of something can transport you to a time so specifically.

Thinking more about the artists, was there much discussion with the bands whilst you were making the films?

DS: All the artists were amazingly helpful in terms of providing their own archive. We did some contemporary interviews – the purists in us wanted to build it all entirely from interviews from the time, but there were things that we needed just to fill in gaps and make certain stories work. They gave up their time and everyone was gracious and helpful, it was a really good process. Also, the community of fans and people who are adjacent to the scene. One of the things that really worked in our favour was making this during lockdown because everybody had time on their hands and they wanted distractions, and I don’t think we might have got as much involvement if it hadn’t been for the sort of unprecedented situation that everybody was in.

So it was a blessing and a curse…

Both: Yeah!

WL: We’ve also had situations where someone says, “I’ve got loads of amazing footage, but it’s in a lock up and I can’t leave my house so you can’t have it”. There were those sorts of things as well, which is a nightmare. But no, like Dylan said I think people love being able to rifle in load of boxes under their bed and find some photographs wouldn’t have happened if you’d done it a year earlier or later. People love to revisit the past.

Lockdown was the point for past reflection, so perhaps it was the perfect time in a weird way?

WL: Yeah, I would agree.

The decision to include Nardwuar’s interview with the Strokes was both genius and funny to a very niche crowd for being so controversial – how did the decision to include it come about?

DS: I think because it was controversial, and because Julian in particular has a very strange relationship with the press and has done since day one – until now. I think showing that conflict in him as a character in that he’s obviously a brilliant songwriter, but very much uncomfortable with the other side of that job which is promoting. There’s this contradiction in him, that he wants to do everything his own way but for it to be very popular.

With Nardwuar, I’ve watched him for years and just wanted to include him anyway! But he also taps into the things that Julian is uncomfortable with. I think also the interesting aspect of that interview is where Nick is trying to deflect for Julian; it also showed a togetherness that wouldn’t be there later on. There were quite a few reasons really.

It has been a great year for music documentaries – Leonard Cohen’s, Moonage Daydream. I wanted to know if this resurge has inspired you to pursue any more musicians?

DS: It’s an interesting question, because we weren’t sure we wanted to make a third music documentary. We’d been exploring non-music stories, but when we read this, we were like Oh, this is so different because it’s as much about time and place as it is about the music. I think we’d definitely do another music documentary, but the three that we’ve made have been so different. The blur one was a reunion plus the history of the band – a quite conventional rock documentary. The LCD one was a concert film. This one is an archive-only time capsule. So, I think if there’s a story that allowed us to do something different with the form, then we’d be really interested in that.

Finally, do you have any artists that you’d just love to make a film about personally?

DS: Well I’m a huge pavement fan, but somebody is already making a pavement documentary! That one sounds interesting, though.

WL: Is it being made already?

DS: Yeah! Part of it is because there’s not a hell of a lot of archives of them, they did this stage musical with people playing Pavement and they ran it for two nights and shot that, and the narrative is this kind of West End musical about Pavement? Sounds bonkers, but good.

What about you, Will?

WL: Yeah, I don’t know! We’ve had starts or tried to make films with different artists – we tried to make a David Bowie film a number of years ago. We started making a film with Bjork that didn’t really get finished. So, in some ways it’s more about finding something with an interesting story rather than going in saying I’d like to make a film about that band or that artist. I think that’s possibly where you end up making something quite conventional, if you’re a huge fan and you just want to make something. It’s about trying to find, like Dylan said, a different way of doing it. Or, finding a story where you know what exists already within the archive! That would be nice, if we were to do that again. [laughs].

Meet Me In The Bathroom releases in UK & Irish cinemas from March 10th.

Stay up to date with Will and Dylan’s work @_32_thirtytwo.

Interview by Lucy Crook