James Sweeney has always been a writer. From putting on shows for his family to acting, writing, directing and producing his first two feature films, Straight Up and Twinless, it’s never felt like an option. He doesn’t shy away from the difficulties of the creative process and, perhaps especially, the financial challenges of his career, but he also sounds entirely enamoured when talking about his work.

Born in Sacramento and raised in Alaska, with only one local cinema, his journey into film began in college, where he started making shorts, many of which he admits “aren’t listed and I hope nobody ever sees.” After creating a proof-of-concept short, he went on to make his first feature film, Straight Up, a romantic screwball comedy, released in 2019.

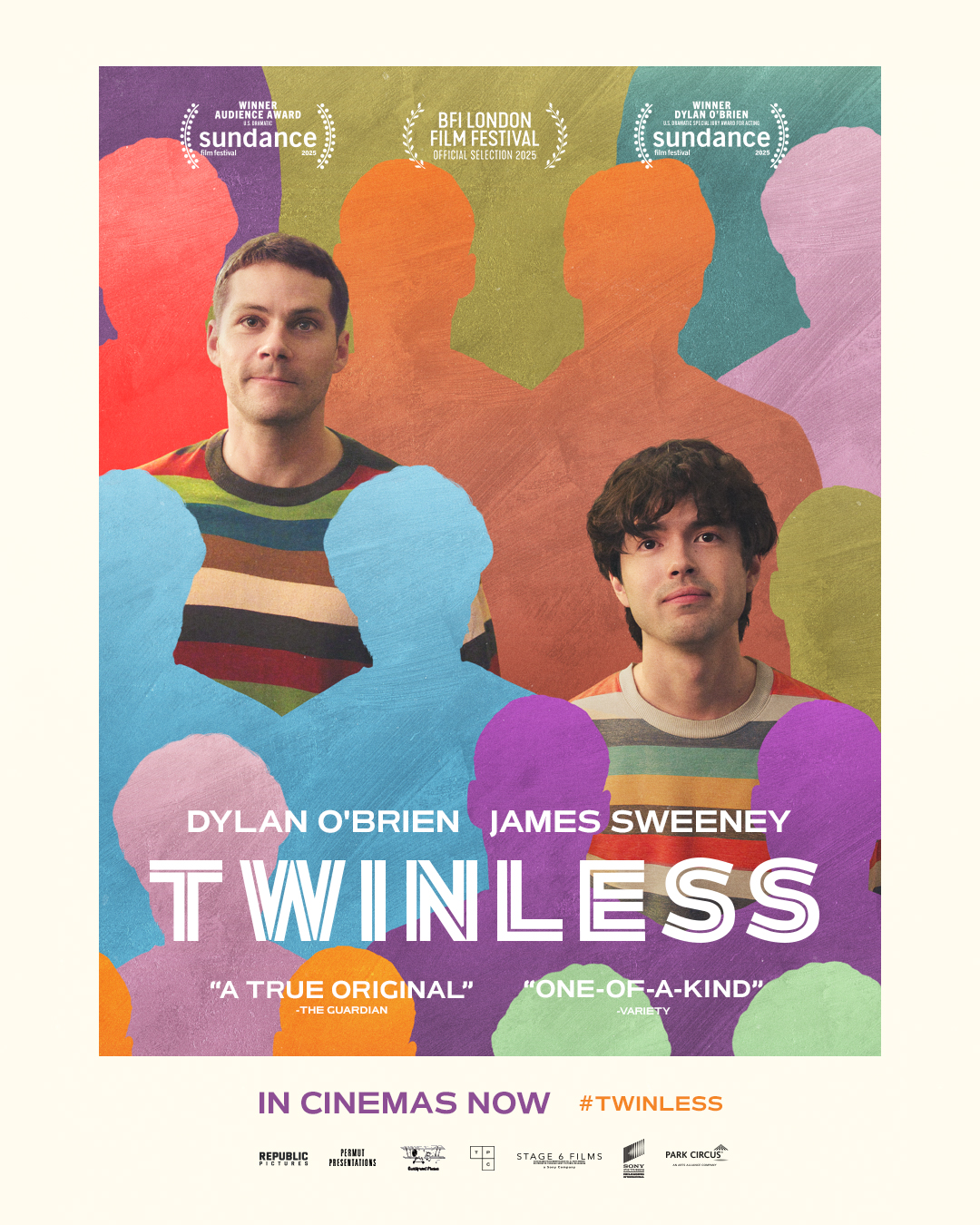

It was through the premiere of Straight Up that he met David Permut, who would go on to produce Sweeney’s second feature, Twinless. A dark comedy, Twinless follows two men — Dennis (played by Sweeney) and Roman (played by Dylan O’Brien) — who meet in a support group for people who have lost their twin, when the two form an unexpected friendship, a twist reveals a lot more about how and why they came to meet.

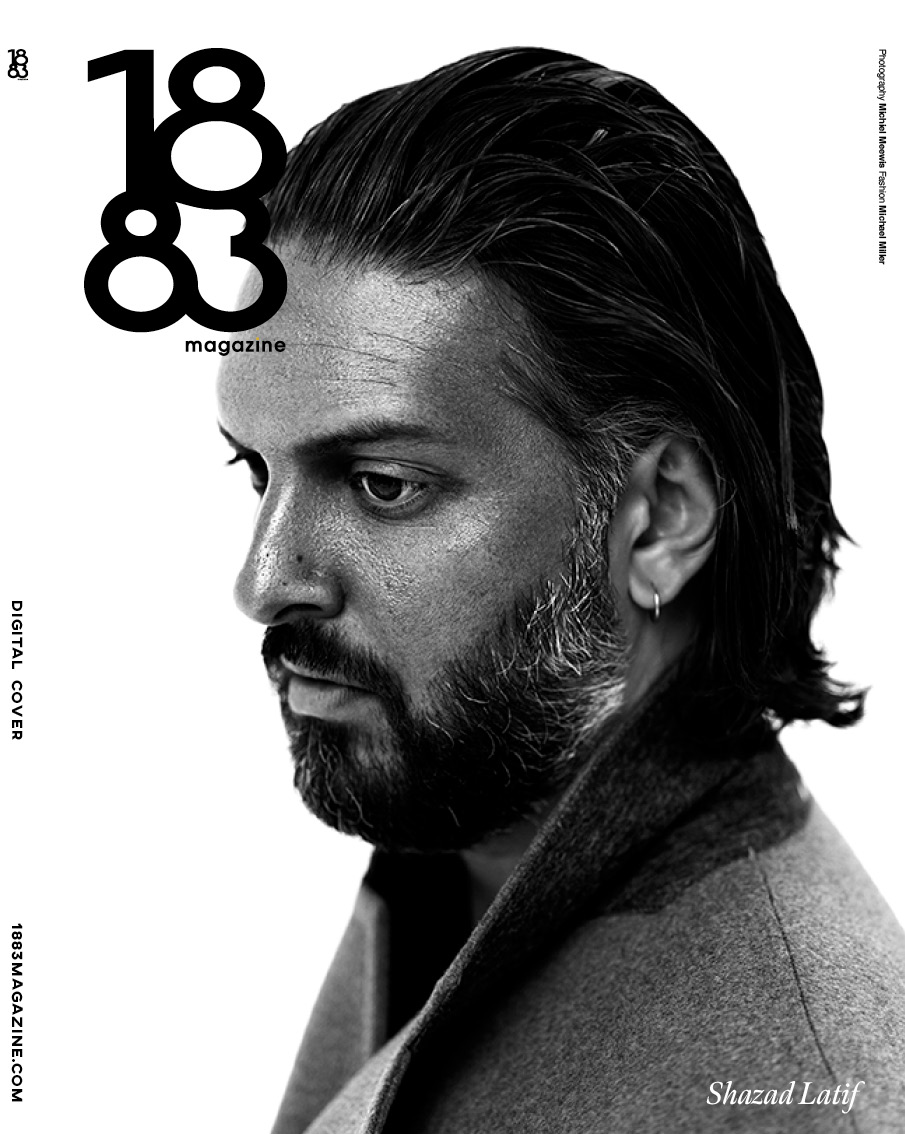

With Twinless now in UK cinemas, 1883 sat down to talk to James Sweeney about his writing process, the long journey of filmmaking, and the balancing act of directing and performing.

You said in the past that romantic comedy shaped your DNA. And Twinless is almost a romantic comedy. What aspects of the genre did you use, and which did you consciously subvert?

Hmm, that’s a good question. You know, my first film, Straight Up, is also a romantic comedy, more in the screwball vein. I think that’s where the more crowd pleasing elements come from. There’s the romantic montage of them spending quality time together. To me, that’s definitely drawn from something that I love in romantic comedies, which is people getting to know each other and sharing experiences.

There’s a meet-cute. There are actually two meet-cutes, and there are a couple of date sequences as well in Twinless. But I guess on a more macro level, it’s borrowing this idea of a significant other. You know, I think in many ways, that’s what the fantasy of twinship was to me as a young boy, is the idea of somebody who fulfills all your needs. And I think we see that have repercussions in these characters’ lives, especially Roman, who is fractured by the loss of his late brother Rocky, and we see so much yearning for an intimacy that was present in his formative years and is very much lacking in the present.

Finding someone who completes and fulfills all your needs is something that’s a bit of a theme in your films: this desire which comes from loneliness. But your characters are just incredibly afraid of commitment as well. Do you think that comes from modern dating culture? Do you think it comes from your own life or from queer identity in general?

Yeah. I mean, I think definitely being queer has shaped the lens with which I see the world. I think there is an element of being queer that’s different from other minorities, where you’re not necessarily born into a community that is a mirror of your own, which is very different from being a twin.

I think what Dennis [in Twinless] talks about is, you’re born alone, you live alone, you die alone. But for twins, that isn’t true. And I think it’s also interesting to me because I’ve written other scripts, also ones that have no role for me, and so I am aware of the parallels between these two films. But I also feel like I try not to overthink what people will take away from my body of work, and leave that open for other people to interpret. And we’ll see if that continues to be a theme in my filmography.

But yeah, I guess I am interested in deconstructing and dissecting part of the fantasy of the romantic comedy. Because I think when you try to put that into practice, you can hit some walls in terms of your expectations. So for me, it’s both an homage and a distillation of that.

What are your favorite romantic comedies?

I love My Best Friend’s Wedding. I love Silver Linings Playbook. 500 Days of Summer, people have called that out to me in terms of style. Groundhog Day. I was late to Notting Hill, but that one really moved me. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

It’s funny, you’re choosing romantic comedies that are also subversive of the genre themselves. So that’s interesting! I want to chat a bit about your script writing process. Do you know from the start if you’re going to act in your films? Do you write for yourself, or is that something that comes further along? How does that work for you?

I’ve done some short films where I had a very clear timeline of when I was writing a character for myself, but I’d say for both Straight Up and Twinless, it wasn’t set in stone. I poured myself into these characters that I played, but I also poured myself into all of my characters. I even did a proof of concept [for Straight Up] that I didn’t star in when I was trying to get the film made. And Twinless, because I started writing in 2015 getting this movie greenlit felt so far away. You know, I was just trying to put one foot in front of the other.

And frankly, I was kind of exhausted when I met David Permut off the heels of Straight Up playing at Outfest in Los Angeles. And I told him about the script of Twinless. I’m sitting behind a poster of a face off, I’m pitching him the logline. He’s like, “I can see the marketing”. And it was really him who emboldened me to do it again. Because it’s so hard, I needed more support. I did get that, Twinless is bigger in scale, but also harder.

Twinless has been a long time coming from that to Sundance to its release now, can you talk about the journey a bit more?

Sure, so I guess timeline clarity. I started writing it in 2015, the tail of it. I don’t think I finished the first draft until spring of 2016.

Still 10 years ago.

Yeah, very long. And then I didn’t get any traction, and I kind of just put it on the back burner. And was really hyper focused on Straight Up. And then I met David in a general meeting, which often never goes anywhere. But he immediately fell in love with the script and sat me down for a steak dinner, even though he doesn’t eat steak, and he gave me the speech that every filmmaker dreams to hear, which is, “I want to make this my next picture”.

So I was working on a significant rewrite of the film while I was preparing for the theatrical release of Straight Up. And then the pandemic happened, so that went to platform release instead of theatres. And the world shut down. So I was rewriting during the pandemic, and we started sharing it with talent. I met Dylan in the fall of 2020 and I thought, “Oh, my God, I got Dylan O’Brien. We’re gonna get the financing!” But for so many reasons, it was very challenging. We had over 100 financiers pass on the film, and then we got greenlit two weeks before the WGA strike, so I’m really great with timing.

It was six months of purgatory, and then we started filming at the end of 2023. It was a very long, demoralising process – Sisyphean, if I may. A part of my life just felt like a reflection of… if I can’t get this done, what am I – it just felt so important to just make the film. We had gotten positive reception to the script, but also a lot of criticism and people not empathising with or understanding, particularly my character. And so I kind of relented that the film would maybe not be for everyone, and not that I think it is now, but it’s obviously been a very lovely reception to the film in a way that has surpassed kind of my wildest expectations based on the journey.

I think Dennis actually is a character that you only like when we see you playing him.

Thank you. It has made me aware of the disparity between how I write versus how it’s received, especially from a cold read. I think people who are more familiar with my voice, or have watched my prior work, had a warmer read of this, but it was still quite a tonal departure from Straight Up and. I think financiers are generally very risk averse and looking for any reason to say no to anything that is “execution-dependent”, as we hear in Hollywood all the time. Hate to hear that, but it’s just an easier thing to say no to.

I remember even doing a table read and I had another actor play the role of Dennis. And he told me, “I didn’t like Dennis”. And in my head, I’m like, “Well, you didn’t say the lines right!”

As a performer, I naturally imbue the character with empathy, because I created him. But an actor’s role is asking how do you breathe life into this character? I think that’s something that Dylan is so phenomenal at, it was there in the script and in my head, but he transcended it. And I think that’s really what you dream of as a filmmaker.

When we see you play him, I think we understand the pain that comes with all of his flaws. How did you bring that in? And you’re also directing Dylan’s own performance. How did you work with him on his performance while working on your own?

Dylan and I have different prep preferences in terms of rehearsal and working style. His training was on Teen Wolf, and I would draw parallels to the rhythms of a soap opera, the pace with which you have to learn. And that was his first job. Whereas I, first of all, compared to him, am extremely green and I grew up doing theater. So I approach things from a vantage point of text analysis, and I feel like the more I rehearse and do a scene, the more I understand it and the better I get. So we had to sort of find a compromise to maintain his sense of spontaneity, but also to make me feel comfortable enough.

I guess that’s sort of the push and pull of being an actor-director is that, as a director, my goal is to create an environment to cultivate the best performances out of my talent, and I try to meet them where they’re at and cater to their process. But sometimes that comes at the expense of my own.

We also did a structured split shoot, which was something that Dylan advocated for in our very first Zoom meeting. He wanted time in between characters, which I love the idea of, but as producer you have to pause because it’s more expensive. We maybe didn’t give him as much time as he would have wanted, but we had a break. I think for him it was more about compartmentalisation and the ability to just focus on one character at a time. But then I had no idea what his Roman would look or sound like when I was initially crafting my Dennis performance, it was an interesting process that very much kept us on our toes. But I think that’s where he really thrives. I was the more manic one. He was having a great time and I’m running around like a chicken with its head cut off!

The way you describe the dynamic kind of sounds a bit like your characters as well. You are panicking the whole time and he’s having a great time. So maybe that worked!

Yeah, I think a lot of things ultimately feed into the energy of the film. I think that we’re aware of that. He was a bit of a leader as well, he’s somebody who the crew really rallies by, and he’s just like a good time and brings a great energy.

How do ideas come to you, how do you know when an idea is a script?

I track and I write things down, and if I keep coming back to the idea, or if I keep thinking of it, or have a new kernel of it pop up, then I feel like there’s something there. Sometimes the notes are a moment of dialogue or a plot point or a character moment. And then I search and think “Oh, I had this idea five years ago!” And it means it’s kind of eating at me, and it’s something I want to explore.

But then on what I prioritise, I’m thinking of the hook, for better or for worse. Can I imagine a tagline or a poster? Is there something there? What about it? Why should I be telling the story? Has it been done before and if it has, what am I craving that’s different.

So why do you want to tell stories? Why are you the person to tell those stories?

I’ve been asking myself that more existentially these days. I think it’s just always been my creative drive. Even when I was a kid, I was putting on shows with my stuffed animals. I started writing plays when I was 13. I wrote my first TV pilot on loose leaf paper when I was in high school. I guess I spent a lot of time in my head. There’s a quote that Sofia Coppola said in the New York Times. I’m going to butcher it, but she talked about how she feels like directing or filmmaking is the way that she gets to make the world exactly how she sees it. And I really resonate with that sentiment, but also to add my own caveat, for me, I’m trying to balance the world as I see it with the world as it is, and trying to find some way to have the two coalesce.

You once said that making films is a bit like sculpting something, which fits with that idea. Do you think it gets a little bit easier? To learn what you’re looking for in a sculpture?

Filmmaking has been described to me as childbirth. I say this not being a woman! But more in that your body physically forgets how painful it is, so that you’ll want to do it again [laugh].

My biggest takeaway from this project has been to trust the process, because each part of it is hard. Writing is hard, post-production is so hard, but I know I’ve done it before and I know it all worked out. I’m actually somebody who has a lot of decision anxiety, which I think is counterintuitive to being a director. But what I love about directing is to reverse entropy, where you start with unlimited choices, and then you have a script, and it can be interpreted in many ways, but you have limited it down now based on the script. Then you’re filming it, and then you wrap principal photography, and you only are able to work with the footage you have, but still, you can edit it in an unlimited number of ways. Slowly, day by day, in post-production, you are making choices deliberately, one by one, until finally you’re left with this one piece of work. And I really like that, to your point, the sculpting process of narrowing it down to like one finite thing, which then you know will be open for interpretation, but also lives forever.

I think that having a tough time making decisions sometimes makes people better directors, because they are able to listen to other people’s opinions a little bit more than maybe if you were dead set on a decision sometimes.

Love that. You should say that to my therapist.

You talk about getting into this almost like it’s propulsive. Like it wasn’t a choice. But you did choose three of the most competitive careers in the world – acting, writing, directing. And you’re doing it, from shorts to features to acclaimed features. How did you do it?

I think for me, I’m very much a believer in growth, and I feel like my career has been very incremental. I don’t feel like I’ve ever been given an opportunity I wasn’t ready for. I feel like, if anything, I’ve been over prepared for each next moment. So for me, yeah, I feel like I learned so much doing all those short films. I’ve been writing scripts. I started getting published when I was 17 years old. I went to film school.

My mind works in a template of precedent. I always think of if something has been done before and if not, why do I think I can do it? I think the real challenge of this career is there is no ladder, there is no meritocracy. It’s so much based on luck. I remember reading Steven Soderbergh’s diary for Sex, Lies and Videotape and the opening page is, “luck is when preparation meets opportunity”, or something very similar to that. You just try to do the work and try to make it undeniable and hope that somebody eventually will give you an opportunity, and then you take that swing and hope it lands in the court.

I’d love to talk about your collaboration with Greg Cotton, your director of photography, because there’s a lot of very interesting decisions made, particularly in Twinless. You do some film, split screens, what were those conversations like?

Greg is my best friend. We met in freshman year of film school. He’s been shooting everything with me for over a decade. So we do have a shorthand, I would say I’m a bit of a driver when it comes to the visual language, and I kind of look to him to tell me how we do it. I think for me, I’m always thinking about how visuals are serving the narrative and theme. We talked a lot about duality, this relationship between authenticity and artifice, which is very much what drives the shooting on multiple formats, both film and digital, and then switching when we do a perspective switch. Even the idea of doing dolly moves for Roman, and then switching to zooms for Dennis, which, in my head, a zoom is a fake dolly. And the audience won’t know that, but they can feel that there’s a difference.

So it’s a collaboration and I really rely on him. I don’t think I could have acted in this film if I didn’t have him. I just have so much trust in him, and he’s just such a wonderful person to have on set. Actors really like him too. I think sometimes that can get overlooked, how much the cinematographer is also a leadership position.

I like how you’re still building characters the whole way through, because you’re building characters as you write them, and then you’re building them visually, and then you’re building them with zooms or dollies. So as writer and director, you get a view of the whole process. How do you begin to build each character?

I would pull from my formative love of theater, but also television, which is very character and dialogue focused. I’ve always felt that dialogue was my forte, like I had an ear for it. And to me, that is so revealing of character. Which is maybe why I’m so academic with my visual grammar, because I have challenged myself to be more visual and approach things in a way that doesn’t just feel like I’m putting a play on camera.

My favorite film of all time is Pleasantville. To me that’s an epitome of a film where you fall in love with this world that is built, so I guess I’m comfortable with characters that feel a little bit larger than life. And again balancing the world as I want it versus as it is. I want it to feel authentic and lived in, but I also don’t just want naturalism. Contemporary cinema leans very heavily on realism, which has influenced my work, but I like there to be a bit of spectacle.

What are you reading? What are you listening to? What are you watching?

I’m reading Less by Andrew Sean Greer. I just also took Rejection by Tony Tulathimutte out from the library, which Alex Russell, who did Lurker, told me to read and to not look up anything about it. So that’s what’s next on my reading list. I’m watching… most recently I loved Pluribus.

And listening to… I’m an album lover, so I’m always looking for an album that I can go back to over and over again. Let me open my Spotify to see what’s on. I did like the new Blood Orange album. I like the Lily Allen album. Right now I’ve been listening to Linda Ronstadt.

My music supervisor has been collecting songs that thematically relate to this new script I’m working on. So I’ve been kind of listening to that a bit as well.

Twinless is now in UK & Irish cinemas. For cinemas visit: https://bit.ly/m/twinlessfilm / PARK CIRCUS

Follow James via @sweeneytawd

Interview Natalia Albin