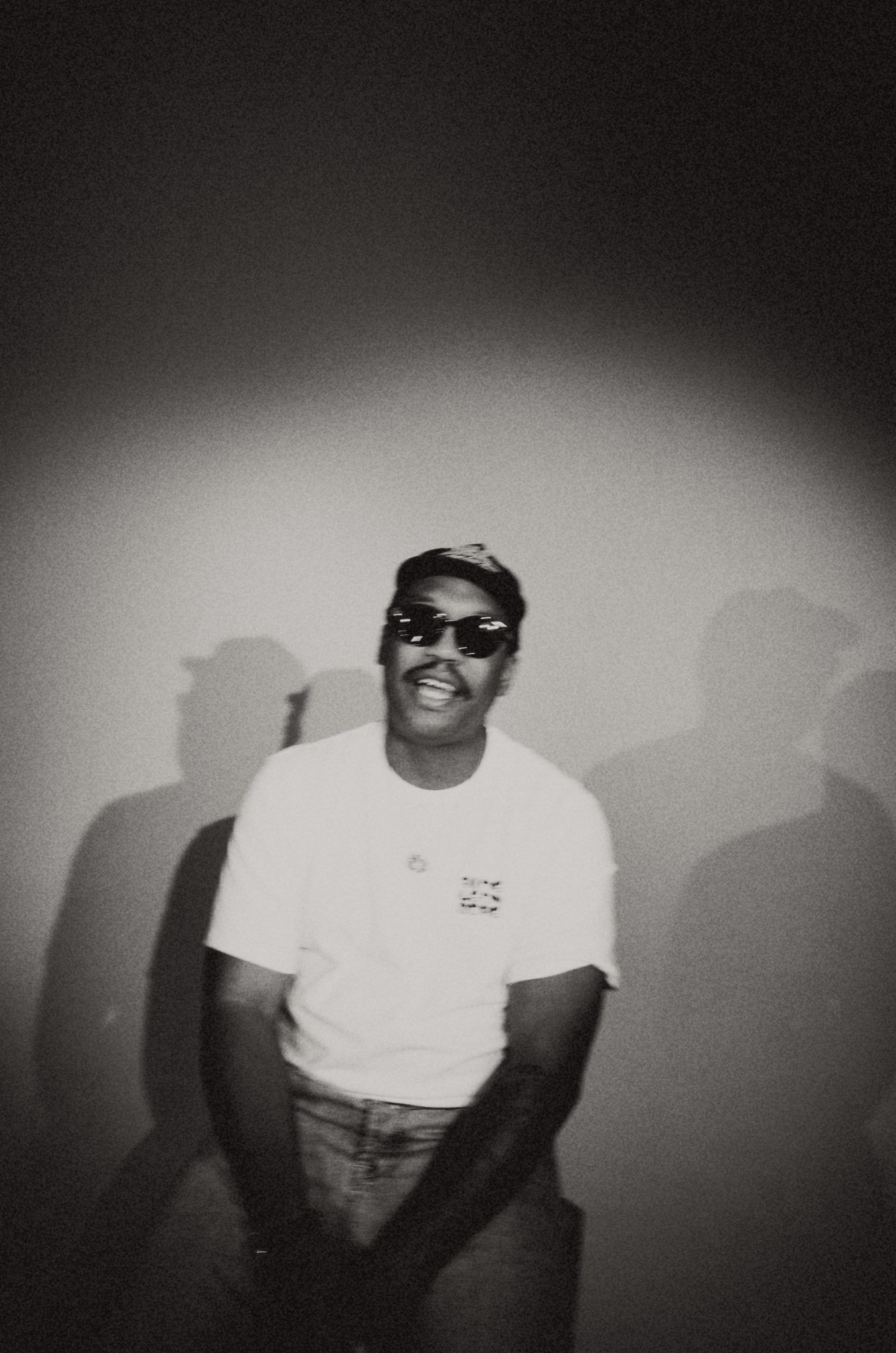

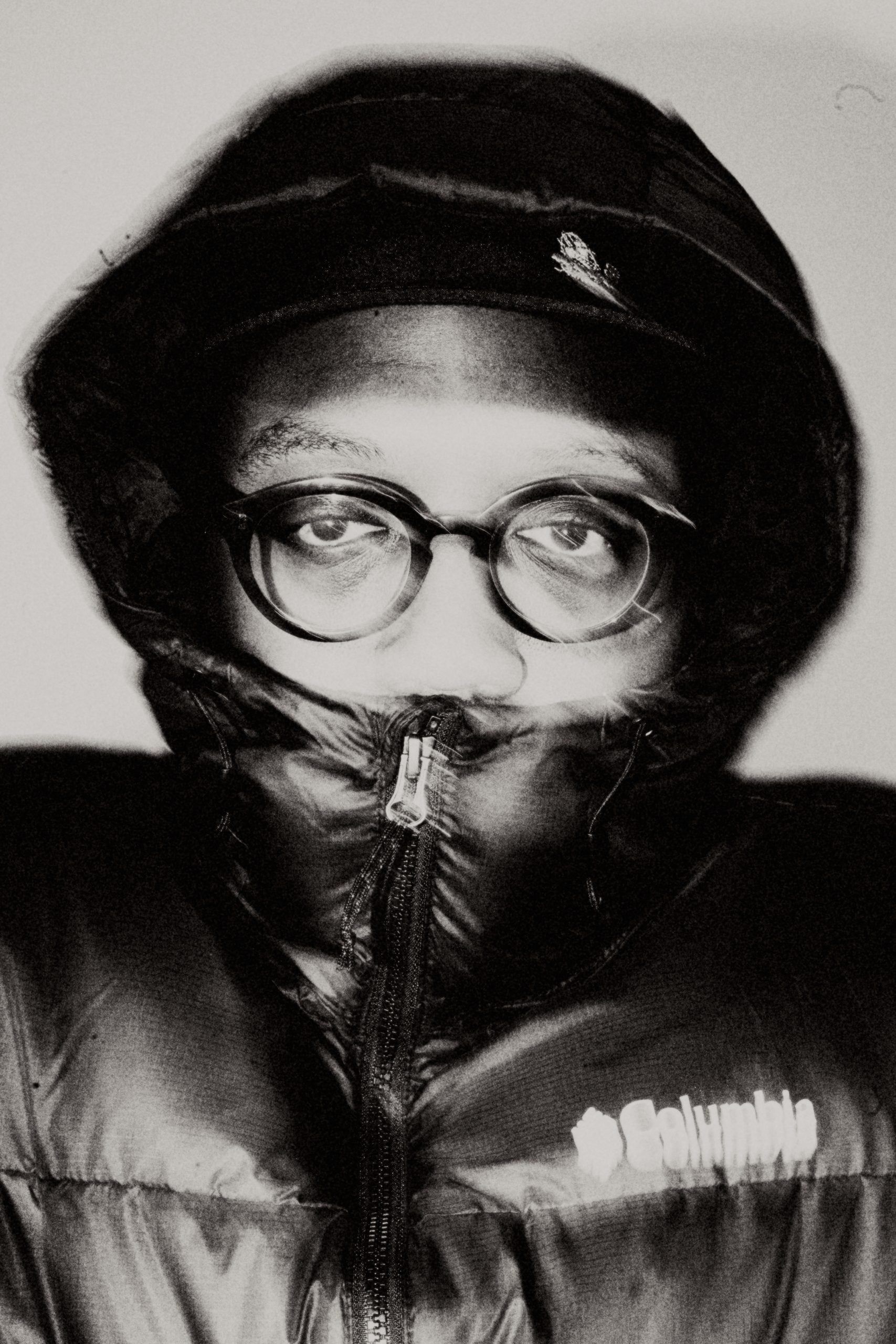

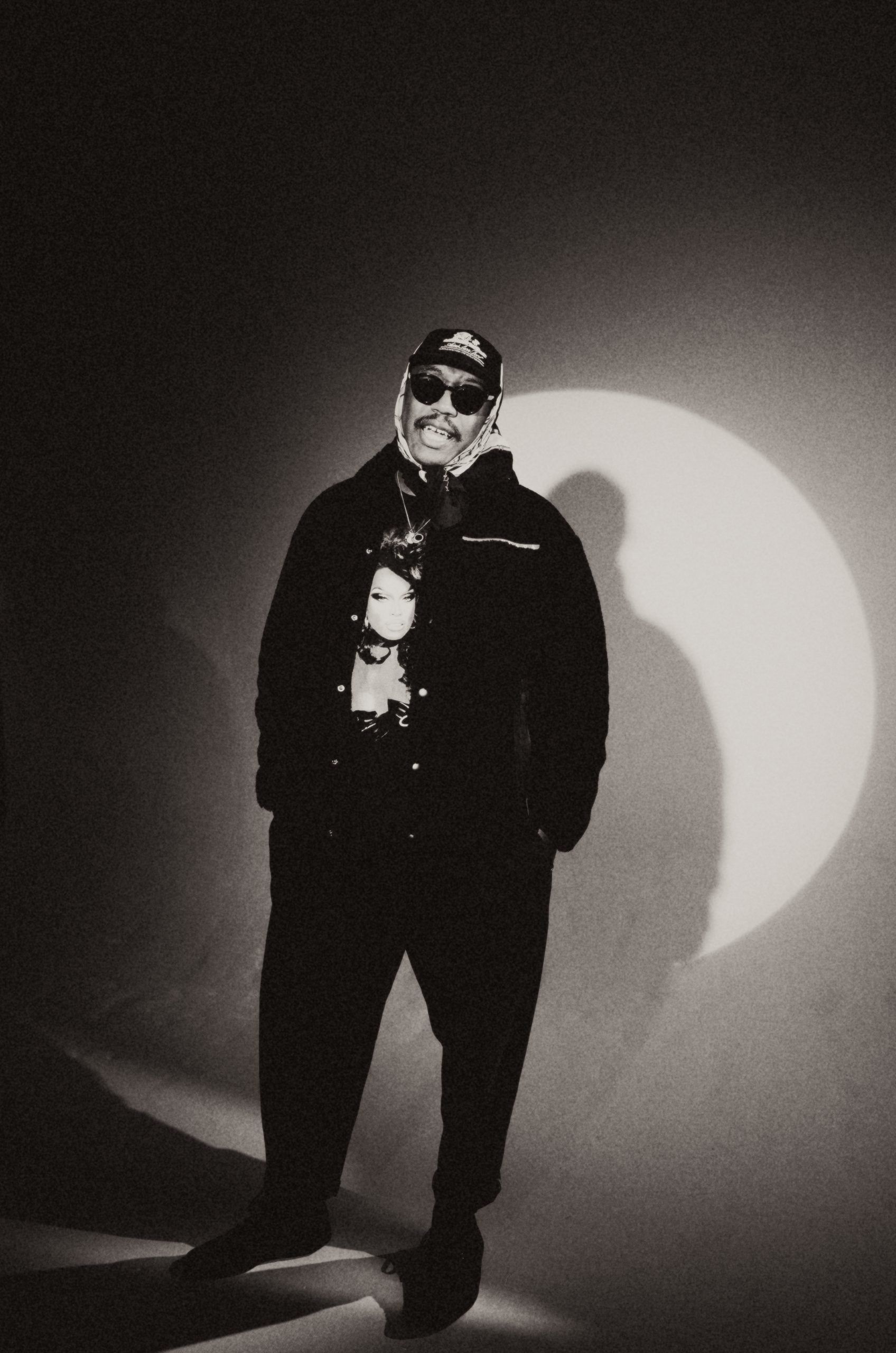

Kevin Morosky

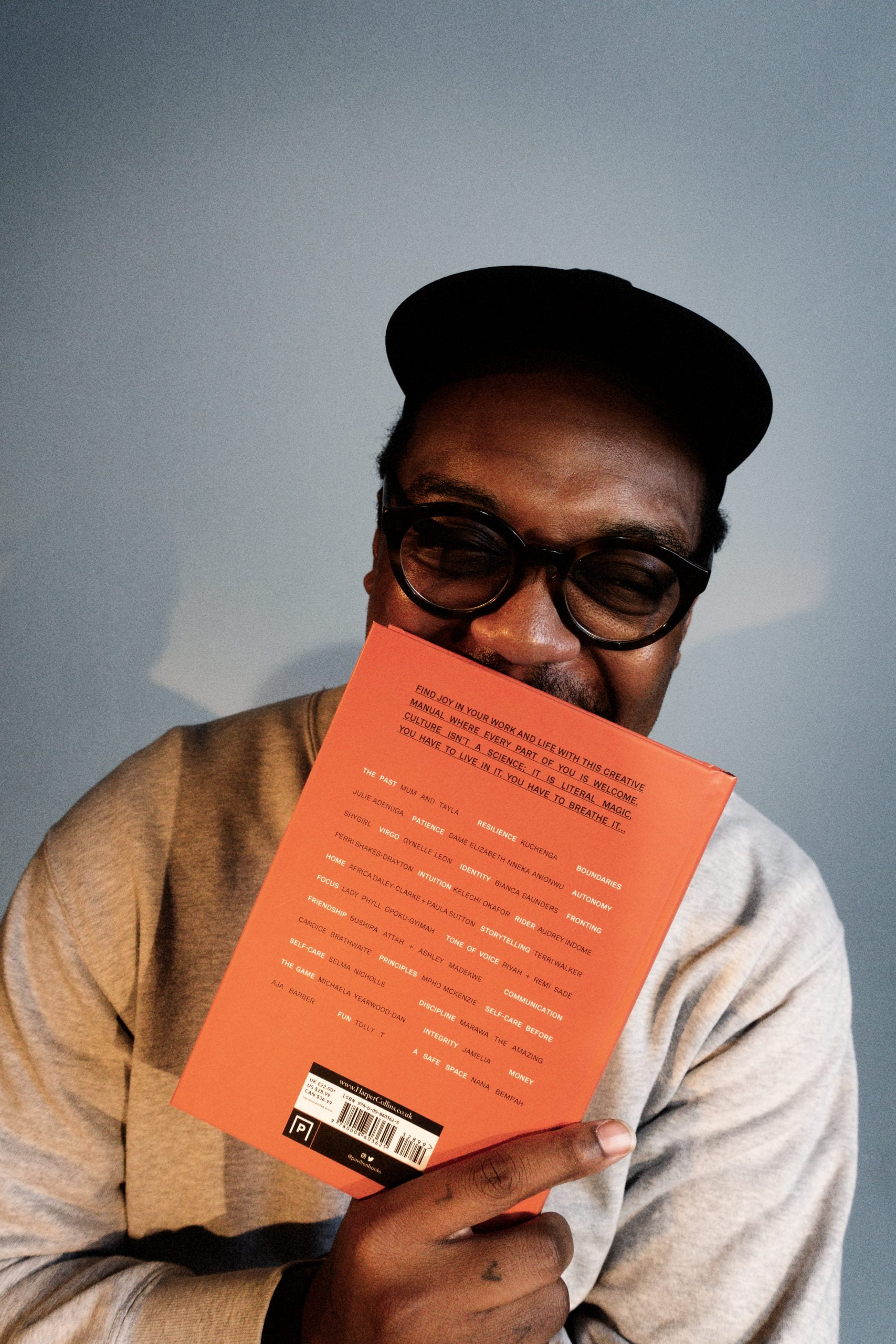

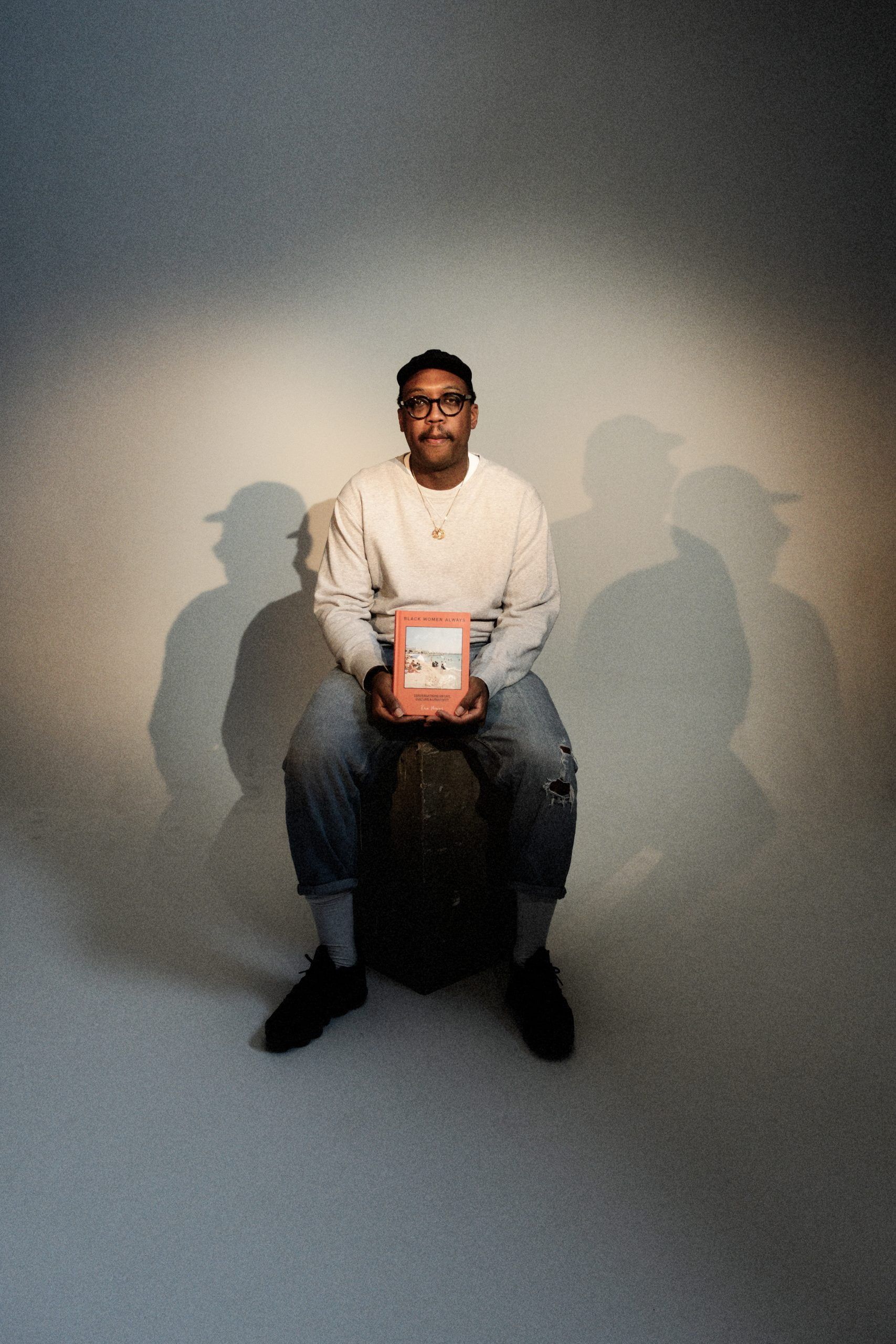

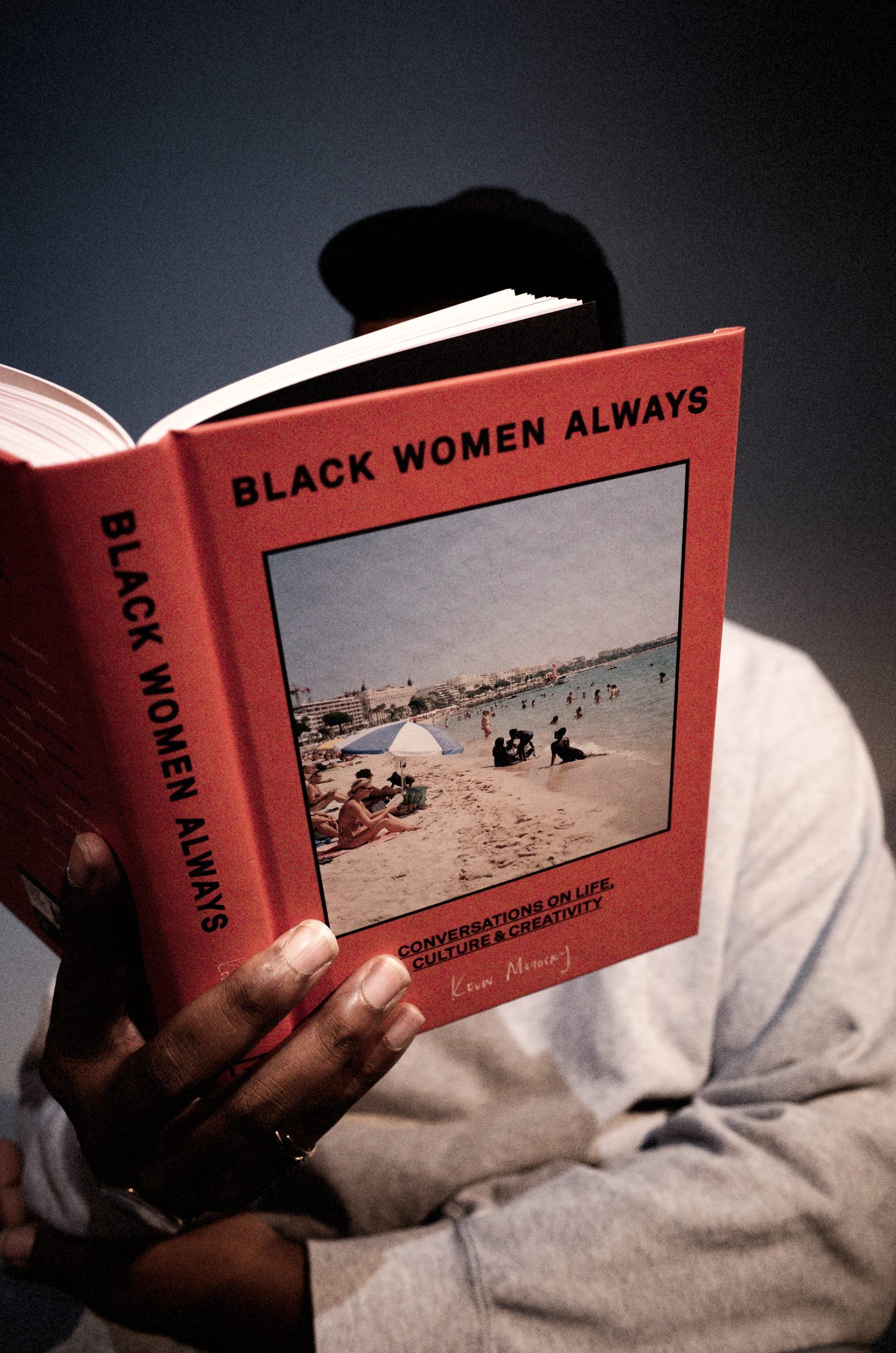

Author Kevin Morosky writes a love letter to Black women in his new book, Black Women Always: Conversations on life, culture and creativity.

An industry-shaping multi-disciplinary creative and film auteur, Kevin Morosky is always immersed in many projects highlighting black and queer identities and emotions. His notable achievements include the award-winning short film Bruce, which aired on Channel 4 in 2021 and was featured at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 2022. Another one of his shorts, Spun, earned the Best Short award at the Bolton Film Festival in the same year. You can also find him writing a funny internet sketch or two with Kelechi Okafor.

His upcoming book Black Women Always: Conversations on life, culture and creativity is a love letter to black women and a collection of conversations with his closest advisors across the creative field, from writers, actresses, artists; friends and family to explore identity, joy and how culture nourishes society.

Kevin Morosky talks with 1883 about his upcoming book, finding peace in creativity, and how Black women have shaped his understanding of the world and culture.

I’m so excited to speak with you and a little intimated. After reading your book, I was just like, “Wow, you are such a brilliant interviewer! You will think I suck!“

No! Absolutely not. First of all, the women I spoke to were friends and family and that made it easy and casual. No need to be intimidated, not at all!

So tell me about what prompted you to write this book?

It’s mainly around [questioning] “How do I know the stuff that I know?” There is a lot of dishonesty in the world right now and a lot of missing context and people not. I detest that, especially as an artist. I think artists, in any form, are natural historians. We dig deep into where [exactly] what we know comes from. I think one of the biggest travesties is when the context of art is never explained. I wanted to check myself on that — I wanted to ensure I wasn’t turning into what I hated the most.

When I look at what I know, how I express myself and my art and dive into it, it was just very clear. I wanted to make it clear that this is where it all comes from. As a Black man, I know that within my community Black men haven’t always lifted Black women.

The minute you said that my face just betrayed my entire thought process.

It’s fine because it’s true! I just think that I had the opportunity to tell this important truth whilst helping people. I’m telling the truth. I’m doing something that’s not been done before in this particular way and I’m also helping younger people. I’m writing a book that I wish I first had when I got into advertising and creative spaces. You go into those spaces and the foundation of those spaces are not fit for people who look like you or I. They don’t incorporate our cultures, lived experiences or the nuances of how we exist in the world. So, I had to write this book, take those rules, and then just dismantle it again in a way that made sense to me and a way that I could use it.

It also makes sense for other people. As I was reading it, there were so many moments where I was nodding along and thinking, “Yeah, exactly.” It’s a very emotional and real book – as you say, these are your friends and family. Do you think that the culture space in the UK actively works to exclude Black women or is it just a natural, consequence?

I think it works to just exclude Black women and not worry about the aftermath. Sometimes I think it’s conscious and sometimes it is just the norm, so people don’t even realise. If we think about who [is in] the childcare and housekeeping spaces — we’re accustomed to using Black women that way and treating them as if they are disposable and take whatever we want.

That point you made about the book being emotional, that’s the biggest compliment ever. We talk about creativity as if emotion is not involved which is silly. All it is emotion and our imagination and so the idea that it’s meant to be this cold, unemotional thing is untrue. [It is true], especially in advertising, where we are selling a dream, a want, a need, and a comfort to other people. Everything we put into those ideas, and what we want to convey to the audience, should be emotional.

Well, it is emotional. It is a book that I wish came out three years ago when I started as a writer. As a Black gay man, what was it like exploring those various emotions that you do without even trying it seems?

I think as a Black gay man, there are lots of spaces that I haven’t been allowed [in], so my emotions have been the space where I have been allowed in if that makes sense. In that respect, I didn’t have a privileged upbringing, but I had love and the space to feel what I felt. My grandmother always said, “If you feel browned off, feel browned off. If you want to cry, cry.”

Big up your grandma.

I miss her dearly. I wish she could have been one of the conversations in this book. It would have been the best time ever. The book is orange, based on her and her love of orange. Her house, everything was just orange and warm.

What is it with orange and black grandmas? My gogo loved orange and bright colours too!

They love colour! But it’s part of those spaces that I was allowed to go into. I’ve always loved words, even though I am dyslexic and sometimes afraid of them. It wasn’t dealt with in the best of ways when I was growing up. And I’ve loved storytelling — storytelling is emotional. Also, I’m a Virgo.

I adored the conversation with your mum — it was relatable as someone who also grew up with a single mum. Why did you think having your Mum alongside Candice Braithwaite and Kelechi was so important?

Well, my mum was my first home. I say this a few times in the book about my grandmother and my mum. Whenever I see skin tones like my mum’s, I instantly feel safe. I also recognise the hardships of being in a creative field and the Black-brown or global majority. More often or not, your parents want you in a traditional job that is more secure than a creative field. At the time when you’re told that you should be a doctor or lawyer and you feel restrained, all your parents are doing is trying to secure your future and you don’t worry like they did. When I was younger, I used to be like, “I can’t wait to have my own house and my letters!” and all that comes through my door are bills. I don’t want any more letters.

Trust me! Like I can’t take the letters.

Trust! I remember thinking, “How did my mum do this?”. There’s a real discourse between parents and their children, but there are reasons behind that. I think the idea of writing a book that is about integrity and respecting the culture and respecting Black women and not including my mum made no sense. I hope people read the chapter and, if they are not close, maybe call up their mum or you can show it to them. Growing up, I thought my mum was annoyed at me, but she was actually fighting hard out in these streets for me and I didn’t know it back then.

Our mums work so incredibly hard!

You don’t know until you’re an adult! This adult thing is hard. I didn’t sign up for this. Just talking to her and reassuring her, that conversation was healing for both of us. Keeping it 100, that have been moments of strain. I’m not easy. My imagination is out of control. I think anything is possible. My standards are ridiculously sky-high!

You talk about how insecure our jobs are compared to the careers our parents choose. Our parents always want us in these secure careers, how did you know you were making the right choice by not going down that path?

When you feel your peace. The peace I found in doing what I wanted to do and executing it in a way. This outweighed any discomfort around money and people not understanding me. As cheesy as it sounds, I was able to look at myself in the mirror and smile at myself. That probably sounds cheesy.

Not cheesy at all! I think that’s lovely.

That was the moment when I [knew] I enjoyed being here and that I understood my purpose. I think the moment I followed that, everything fell into place. I am no longer worried about money in the same way as I was growing up. I accepted that some of my paths will be longer, if not sometimes harder. I am strict with how I do things and my boundaries and my time. I will turn down jobs that probably could have helped me buy a house a while ago, but morally, it wouldn’t feel right. I want to protect that peace I found and look after my creativity. I think when I started in film [after starting in photographer], I was unsure. I was scared to do it my way but I love it. If you pay attention, there are so many influences from the 90s, from my youth.

Your style always reminds me of Do The Right Thing, a very 90s vibe.

While I’m doing great now and have better things coming, when you look back and think of the danger, you start to recognise the world as so much bigger. That time in your life is really special. There’s something in the way we told stories in the 90s — I’m in love with the way songs were made, with a lot of sampling. When you watch my stuff and you hear those VOs and samples, it’s not just me putting stuff together. In the 90s, there was an era of sampling and pulling things together. I am also of a time when arguing on the internet was new — I’m used to the face-to-face. I loved learning the new language of arguing online, using emojis to get your point across, so we pull that in, too. The way the internet looks now is very similar to the inside of my head and that’s why now is so exciting. If you follow me on Instagram, you’ll know.

I do and it’s so funny. You’ll have memes mixed in with serious activist posts. My stories are like that too.

Yeah, because two and three things can be true at once – you can feel so many things.

With regards to the internet and how much of internet culture is influenced by Blackness and Black women. What is your view of the cultural landscape?

I have problems with it, but I do try to give people grace. I think the internet is a new thing and it hasn’t settled yet. One of my talents, as a Virgo — [both laugh]

Mention being a Virgo again.

But I’m good at looking ahead, connecting things, and how they make sense. Some people don’t want to do that, they don’t have the time or their talent is to just live in the moment and enjoy [it]. I’m envious of those people sometimes.

You can’t just sit there and enjoy the memes?

I have to force myself sometimes because as an artist and a historian, I’m always looking at how things connect and what they are referencing and I go down a rabbit hole. I spend half my time in the past and half my time in the future. I look at the internet and think, “Well, that won’t go well” or there is a lesson to learn and it will be beautiful and give new ways of creating and communicating. I think so much of my time is being patient with the internet. Other times I’m just like, “This is wild! Like what’s going on here?”

What is your view on black men and podcasts? We both know there is an issue. [laughs]

It is. What I will say is that sometimes conversations had on podcasts — whether it is about Black women, transpeople, or queer people — it seems they never have those voices in the room when those conversations are being had. That needs to stop. I don’t know how you have conversations about people’s lived experiences and not invite them to speak.

Maybe it’s a patriarchy problem?

Yeah, but you want Black men to be open to having those conversations and not come across as all-knowing and no one else can have an opinion. That is mad because there could be a place about how these men are prosecuted on podcasts and they would come in and say “this is not fair!” like they weren’t just doing that to other groups. You should be big and brave enough to have the people you are talking about on those episodes. I try not to pay them too much mind.

What I love about your book is how each conversation starts with you bringing up a fond memory – whether it’s where you were living or something you recall being said. I loved the conversation you had with Ashley Madekwe when you two talked about living together. Was it important to always include the past in this book?

I like giving context and nuance to everything I say. I wanted people to understand that everything I talk about is based on my life and my experiences. I’m not influenced by the internet; we influence the internet.

Yes! We are the trendsetters. And you articulate that – you cannot have culture without Black people and Black women. What do you want to be realised about the cultural space in terms of blackness?

I think we just need to cultivate spaces for ourselves that fit us. There are so many spaces that just don’t fit us. I’m not saying people who set up these spaces had bad intentions but they are not fit for purpose. I liken it to back in the day when people smoked on the bus and in the club — everything needs to be re-evaluated. We are in these silos and spaces, thinking everything is normal and nothing is normal. We try to ignore it but we can’t. We had time during lockdown to rethink and have been awakened [to] look at what’s not working. Some people were able to go back and be happy with what they were doing before. Others are awake and [they are] not going back to sleep. These things don’t have to last forever or you don’t have to aim for world domination, but if it’s there and helping others then that’s a success.

I mean, you built a collective for people of colour in advertising. Did you feel like that? Like, even if it doesn’t last forever, it was there?

POCC (People of Culture Collective) will be six this year. I say that because I like to remind myself that this is real. People will ask, “Oh, this was in 2020?” but myself and my co-founder [Nana Bempah], we were having these conversations years before. She was the only black producer that I met in all these agencies. We thought we would start this group and probably get 10-20 people. It grows based on what is needed by the community. We started with a small UK group of 200 people, then the American group, women’s groups and LGBTQIA groups. We started facilitating to what people need — producers being paid in parity to directors, making sure meetings aren’t during school drop-offs. With POCC, as I step away, I mainly just want the door to stay open. You saying you wish you had the book three years ago is so great.

I did! Because it was only last year I worked regularly time with a Black editor and your book just really highlighted that community with Black Brits and you mention the culture of South London a lot. What do you love the most?

I like to think one of the kindest people you will meet is from South London. Don’t get on our bad side, but Jamaicans are very welcoming. And being from the South and a Virgo —

You did that on purpose [both laugh].

I’m not, man! I just love it. I just love being from South London. That’s home. I can go through stuff but I’m from the South, so I’ve seen worse.

What else can we look forward to? Are you and Kelechi getting a sketch show?

I want that – Kelechi is amazing and important to me. We enable each other. I’ll say, “I want to do this,” and she’ll just enable me. I’m excited to dive into filmmaking. I watched a beautiful queer film but I realised that the white queer experience was very different from the queer experience that I and other Black people have. We don’t get to see the in-betweens, usually it is coming out and the angst around that, which isn’t always the case. I was making jokes with my mum, as you read, about being gay because I’ve been out for a time. We don’t see that side of the experience in the media a lot. We will go to any Black queer rave, we’ll play the most homophobic songs and take the piss [laughs].

No, that’s so true!

The songs are calling for our ending and we’ll just take misery and turn it into joy. I’m excited to make something portraying that.

I am so excited for your first film! I’ll start the crowdfunding. Cultural highlights – movies, TV, music – go!

If you haven’t seen Past Lives, you should go see it. I want it to get an Oscar, which comes with its issues and why is that standard but I need it to get an Oscar.

I’m so excited to be a country girl for Beyonce. I’m a whole Mariah baby, but I love Beyonce and seeing how hard she worked in Renaissance. She thinks like me — I think one day we’ll be friends. I’m also more excited for Thee Sacred Souls, their music brings me such joy. I would also recommend Blue Eye Samurai on Netflix is wonderful to watch.

I was going to ask about art exhibits but I have no clue what’s on this year. Terrible for a culture writer, I think.

I don’t either. I’ve been writing my book, but I haven’t had time to check!

Black Women Always: Conversations on Life, Culture and Creativity is out now.

Interview Michaela Makusha

Photography Chieska Fortune Smith