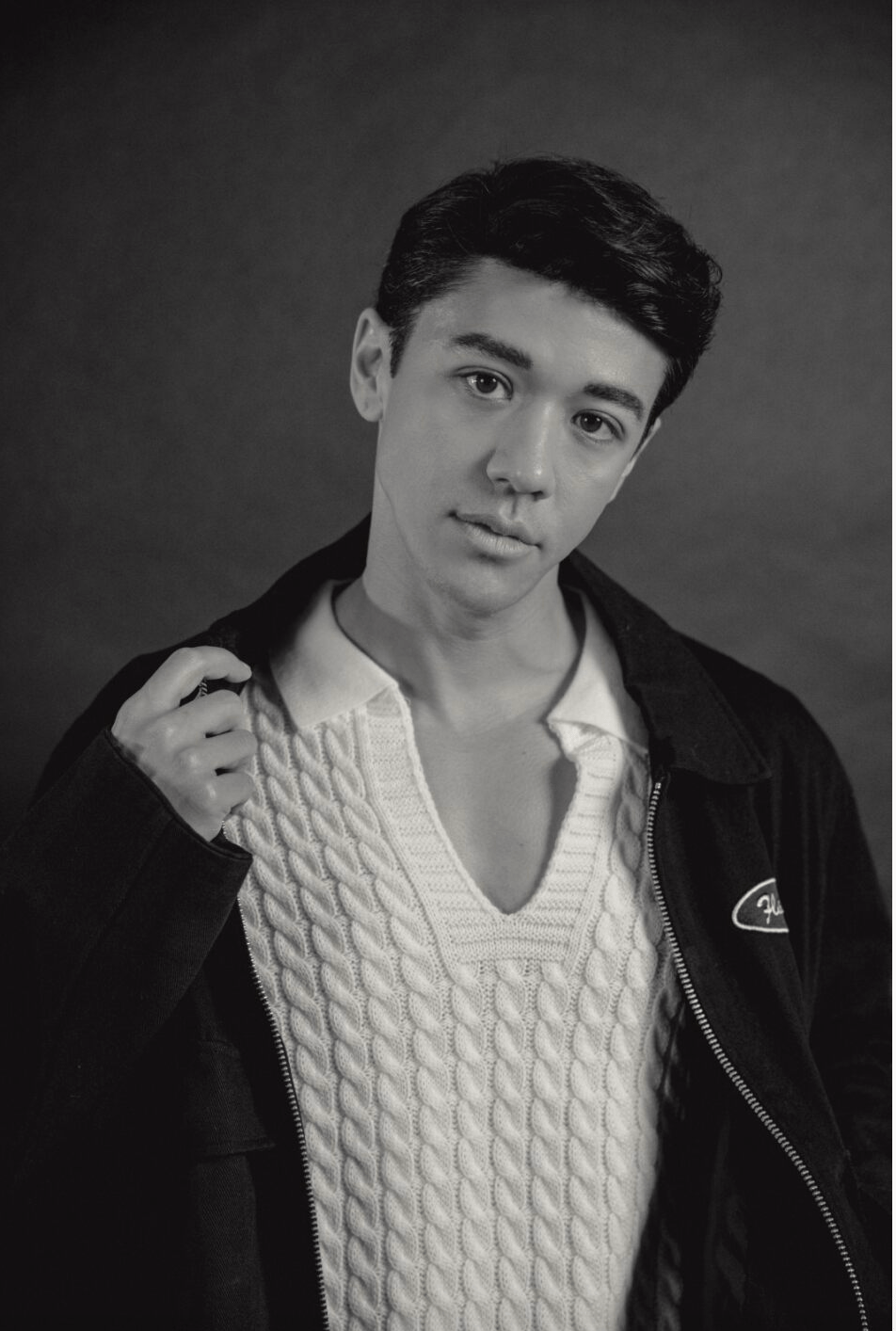

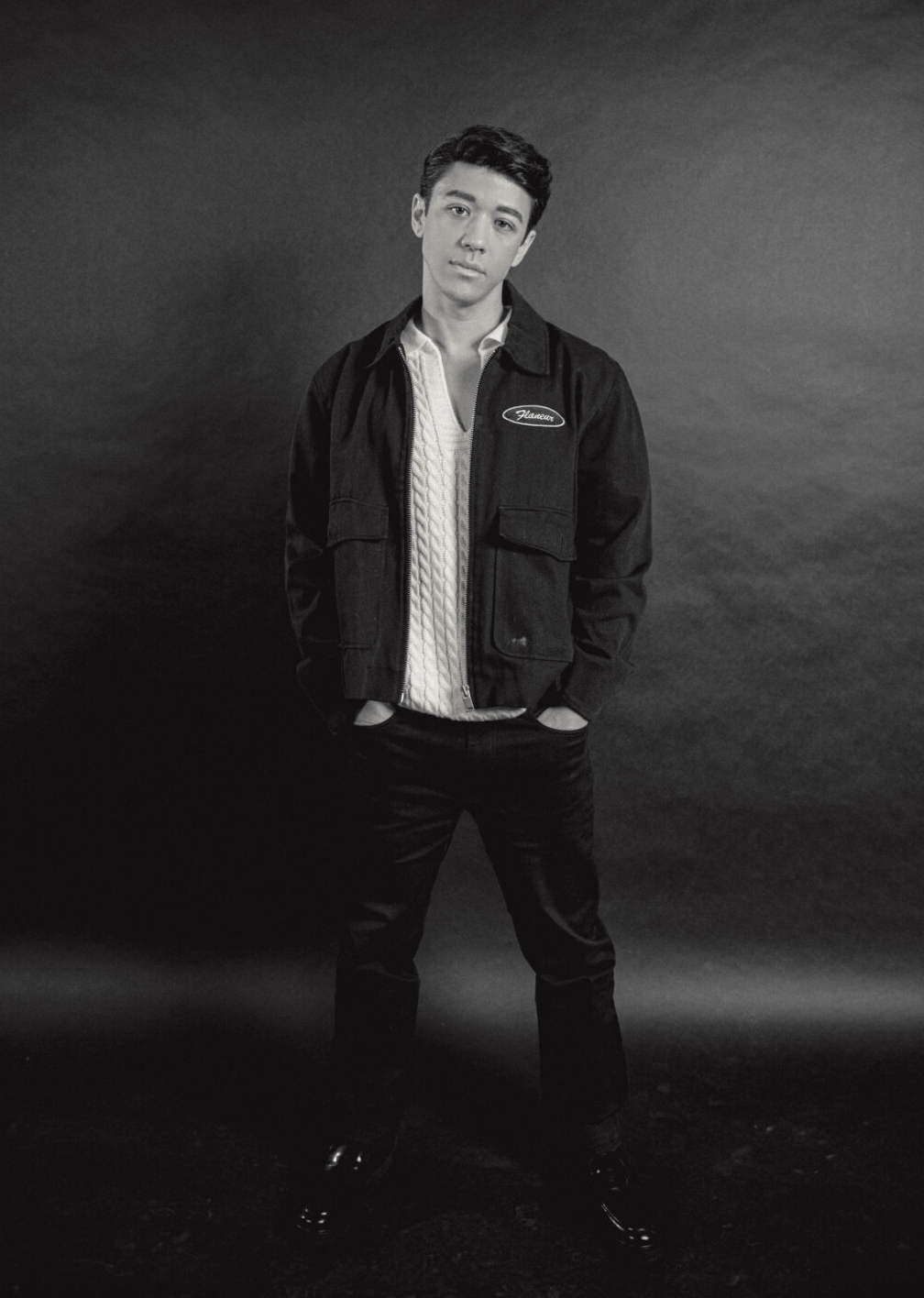

After working with the likes of BLACKPINK, Dove Cameron, and many others, choreographer Kyle Hanagami is undergoing an artistic evolution after bringing Mean Girls from stage to screen.

Born and raised in Los Angeles, choreographer Kyle Hanagami has collaborated with a roster of pop sensations including Justin Bieber, Ariana Grande, Jennifer Lopez, and Dove Cameron. Notably, Hanagami’s collaboration with BLACKPINK stands out, contributing to the creation of iconic dance routines that have mesmerized global audiences. With Mean Girls, Hanagami leaps into a new stage in his career: putting together a musical on screen.

1883 Magazine chats with Hanagami about his choreography work, the process of bringing Mean Girls from stage to screen, and more.

In what ways have you strategically navigated your journey from sharing dance videos on YouTube to becoming a highly sought-after choreographer, effectively bridging the gap between traditional entertainment and the digital landscape?

I think it’s been a process of slowly stepping into different sections of entertainment and making sure that for each one that I do, I put everything behind it and all of my effort and intention into each one and just do each job well as it comes.

How does your academic background, which is not in performing arts but in economics and psychology, contribute to the unique and innovative approach you bring to your choreography, which again challenges traditional perceptions of dance and movement?

I would say that I approach choreography from a very human perspective, and it is always one of my goals to make dance exciting for someone who doesn’t understand dance. I always come from a human perspective, and when it’s choreographing for a major artist, it’s how can I make it so that everybody feels like they can join in? Then, when it comes to movies, it’s how can I make this character feel relatable through movement?

You just mentioned that you like to bring in the human element when you’re choreographing. So, mostly, choreographers take it as just a ‘moment’ thing. The moment a director says cut, it ends over there. How did you come about adding the human element to dancing, and how do you think it helps you as a choreographer?

Choreographers, in general, usually only do one thing. Some choreographers specialize only in choreographing for artists for music videos, and then some choreographers only do film. So, each medium has a very different approach. I would say the common goal is choreographing for TV, film, commercials, music videos, and artists like all of that. The common goal for me is to make people look good.

When you choreograph for an artist, and the artist may have different levels of dance experience, certain things will look good on one person and not on the other. I will think it is great choreography, but then I step into the room and watch the artist attempt it and immediately have to think, “OK, this won’t look good, which means that they won’t feel comfortable, which means they’ll have a level of self-consciousness when they’re performing it.” I want them to feel good. The human element when it comes to choreographing for a character in the film is that you want it to feel cohesive with who the character is. I love that choreography within the film, it’s kind of like you’re baking a cake. You want the movement to feel so cohesive that the flavour isn’t just the frosting on top of the cake. You want it to be the cake itself. You want the cake to be flavoured.

I love the analogy, and as someone who’s been dancing since I was six, it makes sense. While working on the musical and adaptation of Mean Girls, how did you strike a balance between preserving the essence of the beloved story and infusing Tina Fey’s script with fresh and innovative ideas?

Well, the only one-to-one comparison in the entire movie is the Christmas dance, because that is the only dance that was in the original. I think the Christmas dance was a perfect example of the brilliance of Tina Fey’s writing, where it feels genuine. But then there is this off-the-cuff comedy moment that just undercuts everything. It was taking that concept of the tone of her comedy and applying it to everything, making sure that each character’s song felt unique to that character. It was almost like developing each one as their artist.

You just talked about how you try to choreograph each person’s performance based on who they are as a person. Can you give a little insight into what that looked like for each of the characters in the musical?

Let’s consider “Sexy,” which is Avantika’s go-to. It begins with her documenting her preparations for the Halloween dance and then staying in character. There wasn’t a predefined plan for this. It involved figuring out a lot of it as we went along. And it wouldn’t have made sense or stayed true to Karen’s character for her to be executing all these cool TikTok transitions, as I doubt Karen would have the savvy to pull them off. So, we had to ensure that Gretchen was the one behind the camera, guiding her through everything. Then, it was about adding comedic moments for Karen that aligned perfectly with her persona. When she obliviously interrupts Regina’s anger, stepping right in front of her to resume singing because she’s been lost in her world throughout the scene.

And then for Janice’s performance of “I’d Rather Be Me,” we aimed for a more handheld feel. Even the camerawork had a raw quality to it, whereas in Sexy, much of the movement was deliberately directed to make Karen appear as if she was being dragged along. Karen isn’t the type to assert her autonomy and make decisions; she simply drifts until someone takes charge. On the flip side, with “I’d Rather Be Me,” Janice is leading the charge. She’s actively exploring, darting from room to room, and she exudes a sense of control over the number. So, these are two examples that showcase starkly different characters and how their traits influence their movements and performances.

So, is it safe to say that specifically within these two characters, the movement vocabulary was very crucial to who they are as people portrayed in the film?

Oh, absolutely.

How does your commitment to inclusivity manifest in your choice of dancers for Mean Girls? And in what ways does this challenge prevailing stereotypes about the “perfect dancer”?

I mean, I think inclusivity is so important. I think with the cast of Mean Girls, what we were looking for was two things. One was the best of the best. The second was a realistic portrayal of what high school students look like. I think that the dancers we chose for the job luckily checked both boxes. They were the best of the best, and they happened to also look like high school students. And so it turned out to be the best cast.

I love that you said that high school students look like high school kids because that’s not usually the case in movies that we see out there. It was lovely seeing the actual representation of who someone was portraying. Coming back to Tina Fey and building on her remarks about your talent for incorporating humour and storytelling, can you provide specific examples from the film where you showcased that skill in dance numbers, specifically the Christmas one?

Let’s dissect the Christmas dance. So, for the Christmas dance within the movement itself, we had to make sure that it looked like there was a cause to it. It’s supposed to be old choreography, so it had to look like a 14-year-old girl choreographed it. The girls tried to look sexy, but it couldn’t be raunchy. It had to look like it was influenced by what this generation grew up watching. It was taking all of that information and still having to make a catchy dance and then making sure that each of the characters looked like you wanted all of the characters to look good, but you didn’t want them to look phenomenal. You don’t want them to look like professionals because they’re not professionals. You want them to look like who they are. There were times when I would have to be on set and tell Renee or Avantika, “Hey, that was good, can you do it worse?” which is a note that I give very rarely because they were nailing it on set. And I feel like some of the charm and comedy behind it is that they’re not perfect.

But even at the beginning of the routine, like knowing that Cady is being added to this number, the very formation is this diamond formation where you have Regina in the front and Karen and Gretchen flanking her. And then you have Cady, an added piece in the back, totally hidden. You wouldn’t even know that she was there. It’s finding those moments where it’s so hard to pick them out because they’re so soaked into the choreography, song, and the number itself. Even in the scene that happens right beforehand, you have Regina slamming Karen, or you have Regina being mean to Karen and Gretchen right before the dance. Character-wise, you’re watching this unravelling, so building those character beats in was also really important because it leads to Regina’s literal downfall.

What were the considerations and creative decisions behind incorporating elements from BLACKPINK’s routine into the Christmas dancing of Mean Girls? And how did this choice resonate with the younger generation that grew up watching the K Pop group?

Because we were updating the movie for this new generation, I tried to keep in mind what their references would be now. 20 years ago, when that original came out, the references were Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, N’SYNC and Backstreet Boys. Now it’s a completely different landscape in music. So, BLACKPINK is one of the most viewed music artists in the world, so I felt like they influenced this younger generation.

How did your experience with Mean Girls differ from your previous work in films such as Red, White, and Royal Blue and Over the Moon?

Just like no two humans are alike, no two projects are alike. They’re all extremely different. Mean Girls is just different. I don’t know how to explain it. Every cast member is unique, charming, and funny in their way, and you want to bring that out of them. It’s figuring out how to do that time and time again, whether it’s an animated character like Over the Moon or it’s for high school students like Mean Girls.

You mentioned choreographers being able to mould themselves based on situations that come to them. So I feel that that is a great way to stay relevant in the industry after having been there for very, very long. Other than that, what do you think are some key ways in which a choreographer specifically can stay relevant after being in the industry for very, very long?

I don’t know. I’ll tell you when I get there.

You are quite there, so maybe if you can give the top two, that would work.

Ways to stay relevant. I would say the first and most important thing is don’t fall out of love with what you do. That’s the best piece of advice that I’ll ever give. And then I would say, never stop learning. I think it’s very similar to my career path, where I enter different spaces to make sure that I’m still a student as much as I know. So, as I move into film, and then as I move into directing and move into even more, we need….

Areas of interest?

Thank you for the verbiage. As I move into these areas of interest, I want to take lessons, information, and tools from each medium and put them in my tool belt. Now, I have this plethora of knowledge that I can pull from for each project, and that’s how I stay interesting and interested.

I think that is relevant not just to choreography or dance as a whole, but for every profession in general, and you put that in a very nice way. In terms of your involvement in Mean Girls, how did you manage to capture the essence of the Broadway show and translate it into a cinematic experience that resonates with both fans of theatre and newcomers to the story?

I think that the Broadway show was so joyous. One of my really good friends is Ashley Park, who played Gretchen on the show. I went over to her apartment when I was visiting New York, and I was like, “Tell me everything, like breakdown what it is that each of these characters is, like how are these characters different from the movie?” Because they were like little things and nuances. So, for me, it was really important to understand that from the character’s perspective. So when I was preparing for this film, Ashley Park was a huge part of my preparation.

And the Broadway show is so fun, bright, and effervescent that it was figuring out how to take that and update it for film because they’re so different. It’s really hard. It’s really hard to translate from one into the other because, on Broadway, the audience can look anywhere they want to. So, your goal as a choreographer on stage is to tell the audience, in a broad sense, that this is where you should be looking. Film, and with this film in particular, where the directors didn’t want to have big, wide shots of dance, they wanted it to feel very intimate that it was about how do you get the joy and the feeling that you get when you watch something on stage into a screen with limited real estate?

That was supposed to be my next question, and you answered that already. What new projects can we see coming from you specifically in 2024?

There are some things in the works. There is some branching out into different areas of interest, but I would say that I’m excited to step into directing because I was a second-unit director on this film, and it was a huge learning experience for me. Realizing that all of these tools that I had under my belt made me a very competent director already.

How does your philosophy of making dance interesting, for those who may not understand it, align with the role of making digital dance accessible to a global audience? And what implications does this have for the dance industry?

With my choreography, one of the goals is to make sure that the dance is entertaining for people. But also, I genuinely feel like if you do something great, people will see it and appreciate it. So, I never want to dumb things down for an audience. I want to make sure that it’s not interpreted as that. It’s because audiences these days, more so than ever, are smart; they see through inauthenticity. Hence, for me, the choreography and the performance in general need to feel cohesive.

I think everything needs to work together, and it is the same for digital mediums, films, and even music. Everything from the camera to the lighting, the costumes, and the set design needs to work together. So, I’m constantly in contact with every single department to make sure that it feels like each one of these ingredients is getting added to the cake on time as opposed to anything being added last minute.

Interview Ishika Paruthi

Photographer Aaron Idelson