The London chapter was produced by Julia Lei Zhao and curated by Yurui Shi, with Yi Lai serving as executive curator. The exhibition was presented from 15 to 20 December 2025 at The Gallery, 26 Lillie Road. It brought together works by 20 artists from diverse cultural and geographic contexts, marking the gallery’s final show of the year before Christmas. Through a range of practices including installation, moving image, painting, and mixed media, the exhibition examined conditions of presence and disappearance, situating questions of identity, memory, and belonging within contemporary contexts of migration and global mobility.

Losing Ghosts takes the figure of the “ghost” as its curatorial thread, bringing together questions of absence, migration, and the instability of identity. As a metaphor, the ghost is flexible—perhaps too flexible, almost too well suited to contemporary discussions of mobility, memory, and the self. Yet it is precisely this adaptability that introduces a more difficult question as the exhibition unfolds: when the ghost becomes a language that can be readily invoked, does it still generate real tension within the exhibition space?

This question is approached in different ways across the works. Jiacheng Luo and Junyi Qi’s installation Where ( ) Liesdoes not attempt to visualize “home” as an image. Instead, it constructs a situation in which language and the body become tightly entangled. Definitions of “home,” collected from others, are imprinted onto strips of tape and wound repeatedly around a hybrid form composed of soft pillows and rigid plaster. The tape protects and constrains at the same time; language gestures toward belonging while simultaneously forming an invisible cage. The work offers no resolution. Rather, it exposes the search for belonging as a repetitive and necessary ritual—one that is ultimately unfinishable. Here, the ghost feels less like a symbol than a condition: something continuously wrapped, yet never fully placed.

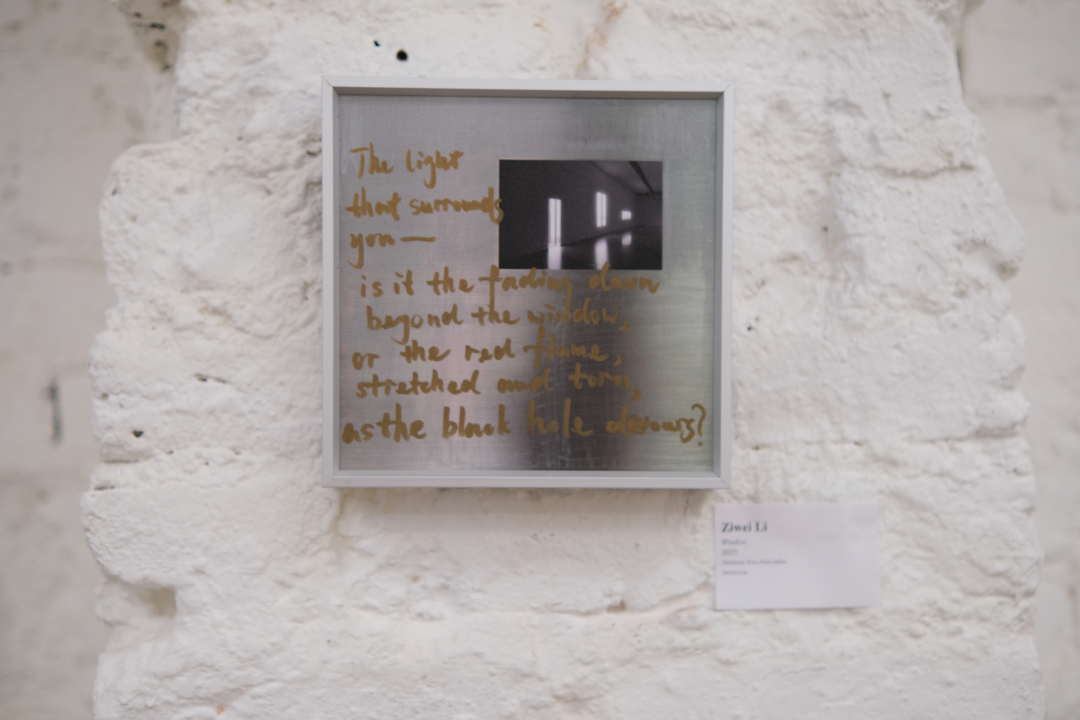

Ziwei Li’s Window approaches the question of belonging from a colder, more paradoxical angle. Built from aluminum, print, and paint marker at a small scale, the work does not offer a view outward so much as it stages a threshold—an image of decision rather than destination. Li’s thinking hinges on an unsettling chromatic coincidence: the red glow of dawn outside a window and the intense red light emitted before a black hole consumes matter. The colours match, but their meanings do not. In this tension—between identical appearances and opposing implications—“home” becomes less a place to return to than a hesitation suspended in light. The work refuses resolution, leaving the viewer with the uneasy sense that the moment of looking is already a moment of choosing.

By contrast, Nata Hamilton’s The House is the Body, the Body is my Home materializes the relationship between home and the body through a carefully assembled constellation of materials. Etched glass, charred pine, rusted steel brackets, horsehair, and satin ribbons form a wall-mounted structure in which surface, texture, and scent carry temporal weight. The semi-transparency of the glass creates a subtle tension between interior and exterior, while the scorched wood and braided elements suggest memory gathered and held, if only temporarily. The work reflects on belonging with considerable self-awareness, yet this clarity also introduces a risk that is difficult to ignore: as the ghost becomes firmly embedded within material and symbolic structures, the ambiguity that might otherwise unsettle the work begins to tighten.

Qingran Liu’s Tears Returned introduces a different register of disappearance—one that is staged less as image than as residue. Constructed from monofilament, wood, wax, and cotton, the work draws on the figure of Lin Daiyu burying fallen flowers in Dream of the Red Chamber, reframing decay as a ritual structure rather than an illustration of loss. Transparent knitted surfaces hover between clarity and imminent fracture; wax “tears” seal and cloud what they touch, as if preservation were inseparable from distortion. Candle traces and dim light lend the installation a faintly theatrical atmosphere, placing the viewer within an unfinished rite. In this work, the ghost does not arrive as a recognizable sign. It lingers as a condition—suspension, binding, and quiet aftermath—resisting the exhibition’s tendency to turn absence into a ready-made metaphor.

Taken together, these works generate a tension that does not belong to any single piece, but rather emerges from the exhibition’s structure as a whole. On one hand, Losing Ghosts brings together practices that engage migration, memory, and identity with genuine sensitivity. On the other, the ghost, as a curatorial language, sometimes begins to operate as a generalized framework, drawing disparate works too closely together at the level of meaning.

This unevenness becomes especially legible in the works that insist on their own material or narrative logic. In Shuyang Chen’s The Vile Wind, dream-based imagery holds memory in a state of atmospheric instability, where presence is sensed like weather rather than secured as statement. Zihan Mei’s video game Point-to-Point Adventure makes attention itself measurable, rewarding proximity yet allowing value to drain when the encounter is abandoned. Elsewhere, Luna Meng’s The Empty Cage holds absence as a lingering architecture, while Julia Lei Zhao’s video 27,001 OF ME extends the question of disappearance into the digital afterlife of the body, where visibility becomes indefinite and ethically uneasy.

Within an open-call context, this condition is familiar. When a theme is highly inclusive, artists often adjust the way their work is narrated in order to enter the exhibition’s conceptual space. This is neither a simple compromise nor an ethical failure. Still, it points to a broader reality: as practices are repeatedly aligned with a shared language, original motivations may drift, and eventually become obscured at the level of discourse.

From this perspective, Losing Ghosts does more than address loss and ambiguity of identity. It also, perhaps unintentionally, stages the mechanisms through which such forms of “losing” take place. The exhibition’s most compelling moments emerge where the ghost is allowed to remain unstable—where absence is held as a condition rather than converted too quickly into image or meaning.

Featured Artists:

Nataliya Belova, Ling (Yiling) Cao, Shuyang Chen, Lila Cobryn, Jude Cui, Nata Hamilton, Jingchen Han, Jing Hsu, Joseph Le Fevre, Ziwei Li, Layla Yuanxing Lin, Qingran Liu, Alex Loughrey, Jiacheng Luo & Junyi Qi, Zihan Mei, Luna Meng, Xinyi Xu, Yike Zhan, Julia Lei Zhao, Coraline Mengdie Zhou

Producer:

Julia Lei Zhao

Curator:

Yurui Shi

Executive Curator:

Yi Lai

Special Thanks:

Freya (Yiyi) Chen, Yangshun (Rachel) Chen, Latifah (Siyu zhang), Yi Huang, Jingxi Li, Mingyan Ji

Photo Credit:

Joy (Junting) Zhou, Freya (Yiyi) Chen