Exclusive interview with Italian artist Lucia di Luciano, on the occasion of her US Debut with Lovay Fine Arts @ Independent 20th Century Fair, New York

1. You began your artistic journey in the 1950s, at a time when being a woman in the art world came with many challenges. Looking back, what do you remember most vividly about those early struggles and breakthroughs?

Women must be able to express themselves with the same opportunities as men.

This simple observation seems trivial today, but you have to remember that in the 1950s, this was not a given.

From the very beginning, my story has always been a struggle to gain recognition as an artist. Starting with my family, I was born in Sicily and had to fight relentlessly to be able to move to Rome and attend the Academy. My family was very wealthy, but even so, in the early 1950s, it was scandalous to even think that a girl from high society could pursue a career as a painter, a role that was then exclusively male.

I want to remind you that back then, especially in the 1950s, but also in the 1960s, entering the world of artists was no walk in the park for a woman. It was a world of men, male professors, male artists, male gallery owners. Just think, in my class at the Accademia del Nudo, then at Villa Medici, I was the only woman (apart from the prostitutes who worked as models, laughs). Even there, you had to be accepted by a world of future artists who were always men.

But the female artists of that time were neither dolls nor idiots, and in the 1960s, particularly in Rome, the situation changed dramatically. In my opinion, the constant presence of female painters was the real novelty of the scene in those years. I fondly remember many of my friends from that time: Bice Lazzari, Lia Drei, Maria Lai, Nedda Guidi, Rosanna Lancia, Carla Accardi; women with strong characters; today I feel alone.

2. Arte Programmata in the 1960s was groundbreaking. What drew you to geometric abstraction and programmed systems at that time? You and your late husband, Giovanni Pizzo were pivotal to this movement. How did your artistic partnership influence your own practice?

For me, but also for some of our other painter friends, Piet Mondrian’s works, exhibited for the first time in Rome, were a shock. They left me extraordinarily curious; I had never seen anything like them before. My husband and I immediately thought that everything we had painted before was worthless and that Mondrian’s works were asking us to go beyond simply abstract painting; it was the prelude to our future work. I had always looked at, let’s say, stolen what was being done at the time, because I was young… due to my age, I couldn’t have had any great ideas, but I always went looking for them among painters who were worth their salt.

I have never been a great theorist, but I had valuable help in this field from my husband, a great reader and scholar of Gestalt literature, Piaget, and perception theorists such as Itten and Munsell.

Mathematics was very important. I constantly used mathematical permutations at least until 2000, then, with greater freedom, I moved on to less restrictive signs, but the idea of a geometric form has always been fundamental in my work.

3. Do you feel today’s generation of artists has a comparable movement that parallels the spirit of Arte Programmata?

Today, I find it difficult to give advice on how to pursue one’s art. In my day, artists felt the need to meet and discuss things together. I think back to my participation in Gruppo 63 or Operativo R, as well as Spaziodocumento. In our youth, exchanging opinions and searching for a single field of operation was felt to be an obligation, and this also led to personal evolution. Now I see that young people have lost this ability to come together, so I would suggest that they at least choose the best schools and the best teachers for their training.

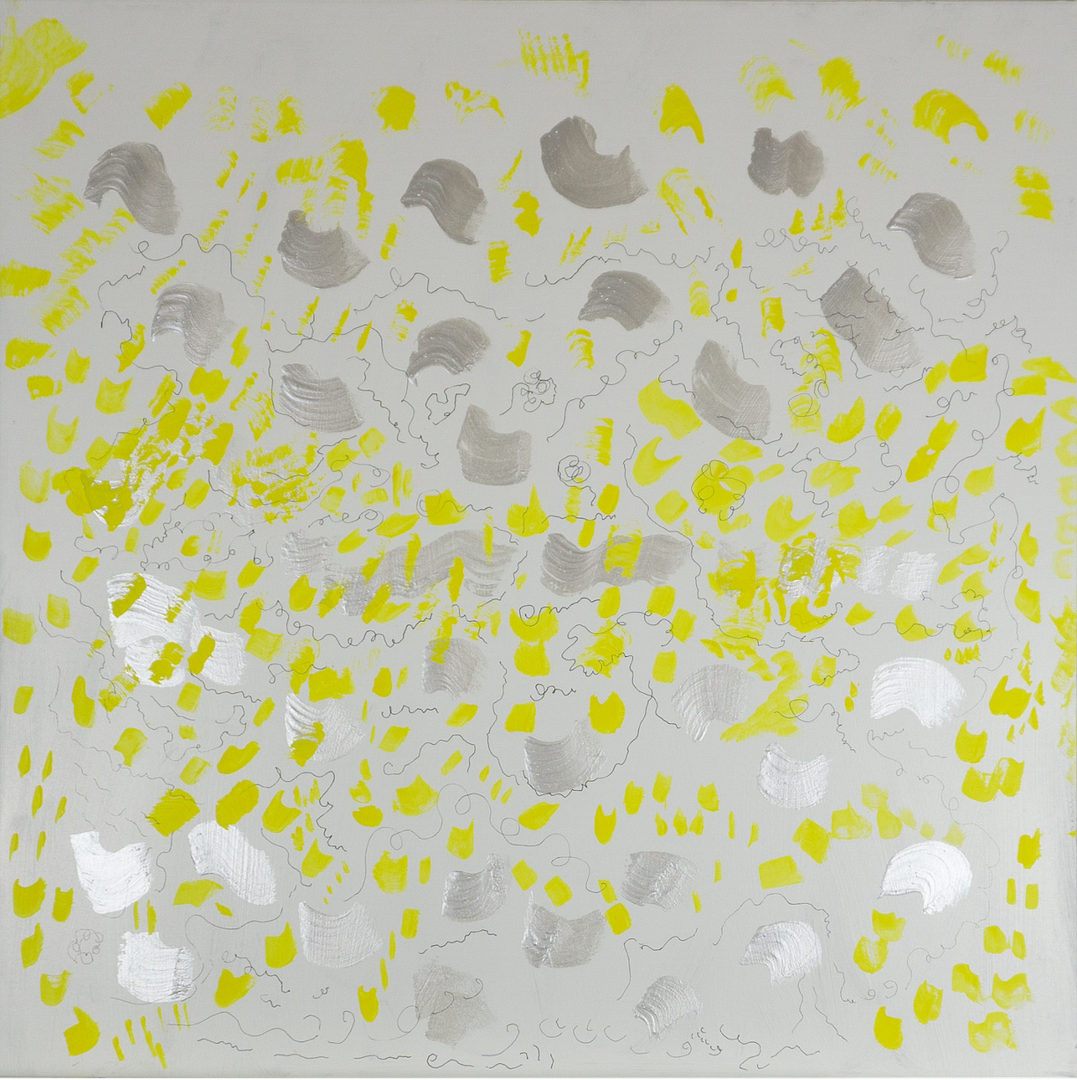

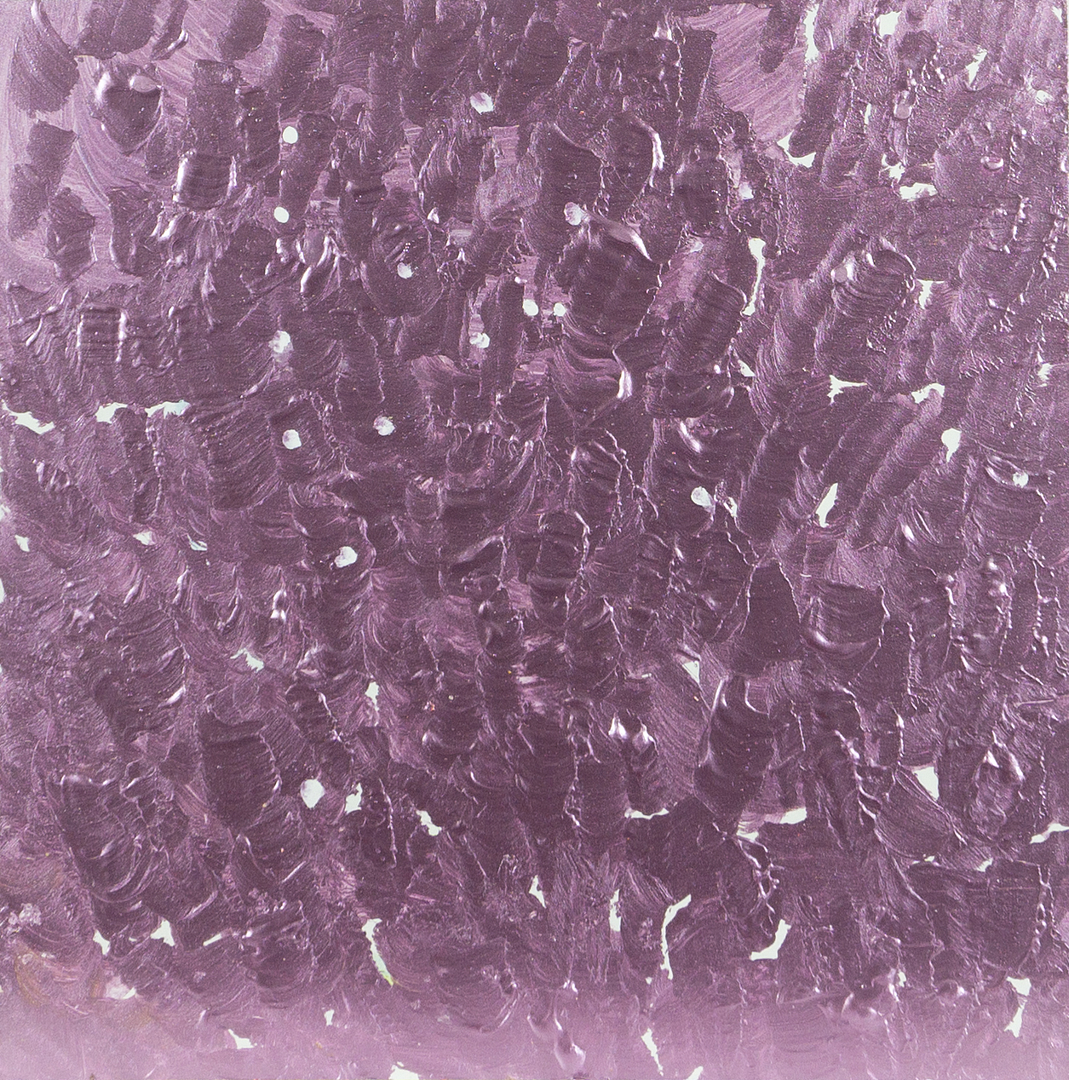

4. Over the decades, your work transitioned from strict black-and-white geometric forms to vibrant, experimental abstraction. What sparked this transformation toward color, gesture, and emotional expression?

My work has been a continuous transformation. I am a woman who moves forward, I want to move forward, my life is made up of painting, I love only painting. But my painting must change so as not to remain in the fog of routine. I wake up in the morning, as I have done for seventy years now, and think: how can I express myself better today than yesterday?

5. You’ve said, “My work has been a continuous transformation. Today, at 93, I get up in the morning and think about how I can express myself better than yesterday.” What fuels this sense of reinvention for you?

Well, I don’t know the secret of my energy, we’ll have to ask someone else. All I know is that I get up in the morning and start saying, “I’m leaving.” Then I go to the room where the painting is, I approach the table, I take the pens, the brushes, and at a certain point, while I’m using the pencil, the painting I want to do comes to mind. That’s what I have. I only have the painting in my brain!

6. In your recent works, you merge influences from Op Art, color field, expressionism, outsider art, and even non-Western traditions. How do you navigate between all these artistic languages while keeping your voice distinct?

Art is ideas that come into your brain and are things you need. Even before you start, you need something that gives you tenderness, joy, all good things. I can’t be without anything, I have to build, I have to paint, and if I paint, everything is fine. If someone takes painting away from me, I am sad.

7. You’ve spoken about the difficulty of being recognized as a woman artist. Do you feel the landscape has truly changed for younger female artists today?

I think so, on the one hand it’s easier, on the other there are too many artists or pseudo-artists, before there were only a few of us, with more original and authentic approaches to their art.

8. You mentioned that women of your generation in art were “women with strong characters.” How important was character in surviving in such a male-dominated environment?

Times have changed. In the 1950s, for a woman, let alone a woman from southern Italy, the idea of becoming a painter was unthinkable for society and for your family. At best, it could be a hobby. I was lucky, or rather, I was smart to marry an artist, which opened doors that would otherwise have remained closed.

Today, all that has disappeared, finally! The problems women face today in our artistic world are only a fraction of what they used to be. It seems to me that the problem is more about job opportunities for all young artists, not just young female artists.

9. Your works were featured at the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022, a huge recognition. How did that moment feel after decades of quiet dedication?

It was a great satisfaction to see over seventy years of work being recognized at the Venice Biennale. The paintings were superbly displayed and attracted as much attention as the important exhibitions of the 1960s.

10. After nearly 30 years of not showing your contemporary work, you returned with major exhibitions. What was it like stepping back into the public eye at this stage of your career?

For 40 years, we voluntarily isolated ourselves in a remote location in the countryside, our villa in Formello (near Rome), to work on our painting every day. No exhibitions, no trips, just painting, morning and evening. Your life always changes. After all these years, you acquire such a personal vision of yourself that your painting becomes you; resuming exhibitions, even important ones, is not the fulfillment of life. Yes, of course, it’s nice, I don’t dispute that, but I am my paintings, and I am my favorite exhibition.

11. At 93, many might slow down, but you seem to be in a period of deep creative energy. What keeps you in love with the act of making?

If I don’t have painting, I am sad. It’s useless to tell me, “What are you doing? Get some rest, at your age.” No, if I stop, I am sad. If I take away painting, it means I am boarding on a frightening journey into darkness, and I cannot think only of the color black. I live for all colors.

12. If you could give advice to your younger self, the young artist in Rome in the 1950s, what would you tell her?

To make the same choices again, always with the same energy and passion of a Sicilian woman.

13. How has the collaboration with Lovay Fine Arts supported your international presence in both the USA and EEA? What are the highlights of your collaboration?

Ah, Lovay Gallery for me is all about Balthazar Lovay: a lovely person, a young man so in love with my painting! He immediately understood my latest works and knew how to appreciate them. When I visited his gallery in Geneva, I immediately noticed his elegance in arranging them. I like his sensitivity.

14. And finally, what do you hope viewers feel when they stand in front of your latest works at Independent 20th Century in New York?

I wish to transmit my love for colors, and I hope that, like in my case, they are ‘filled’ with colors every moment of the day. I’m crazy about colors!

Don’t miss Lucia di Luciano’s works currently on view at the Lovay Fine Arts booth @ Independent 20th Century Fair in New York, running from 4-7 September 2025.