‘I am always looking for things to put on my flat perspective surfaces.’ Patrick Hughes’ 60 Years of Art is witty and ironic at times but is ultimately a sincere and poignant reflection on art as it stands now.

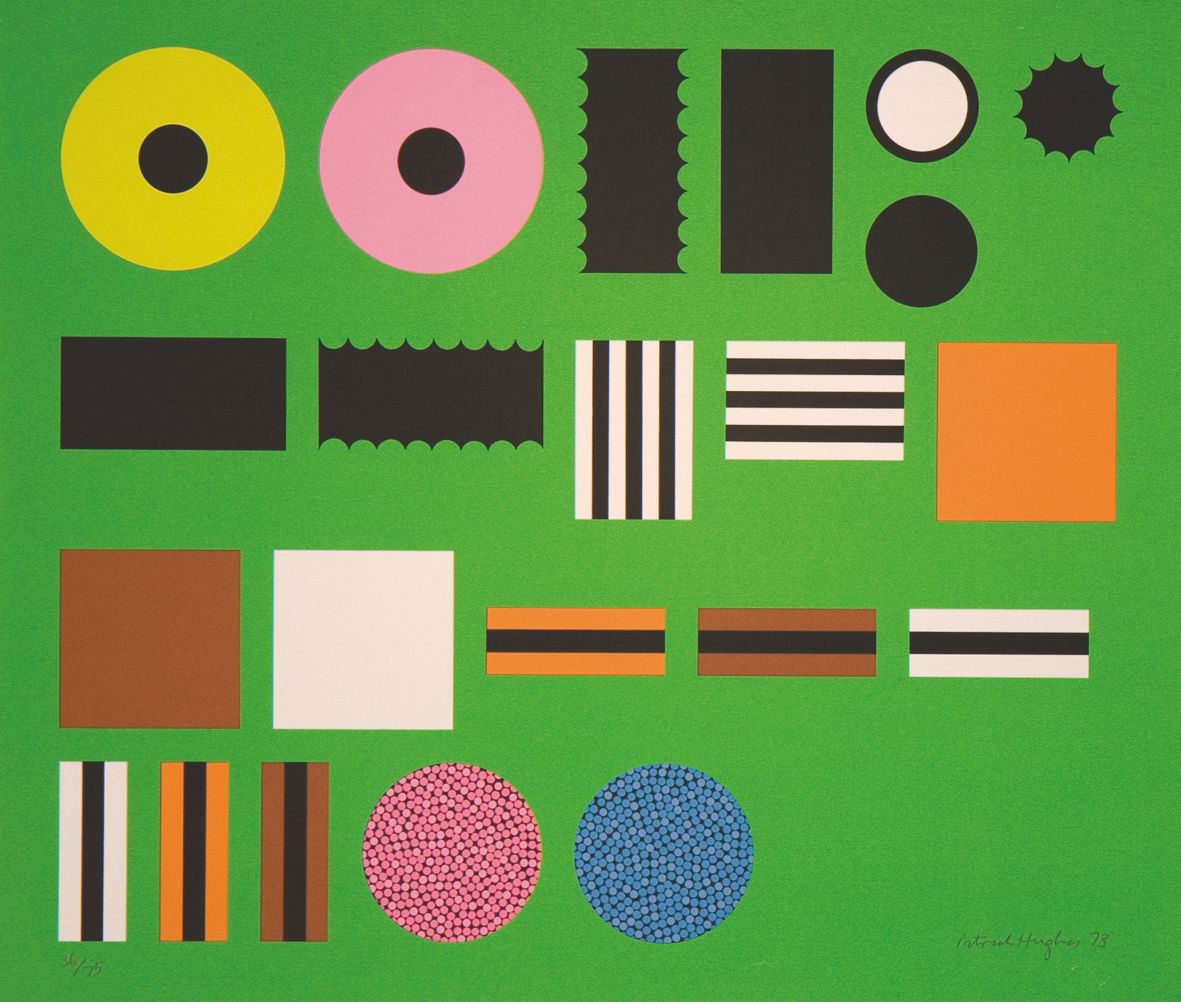

It is easy to underestimate the significance of the passing of 60 years; while we might like to think that this is a fathomable timeframe, for most of us it is impossible to comprehend this amount of change. Patrick Hughes’ solo show, 60 Years of Art, showing at Bel-Air Fine Art London from 13th November to 15th December 2019 presents us with a testament to the latter half of the 20th century, ongoing into the 21st. From the conceptual surrealism and pop-art of his early years to his more recent reverspectives, which shatter our unquestioning reliance on day-to-day depth perception, Hughes’ chronology takes us on a journey not only through the life of one of the most influential British artists but also through the mutating nature of a modernising society.

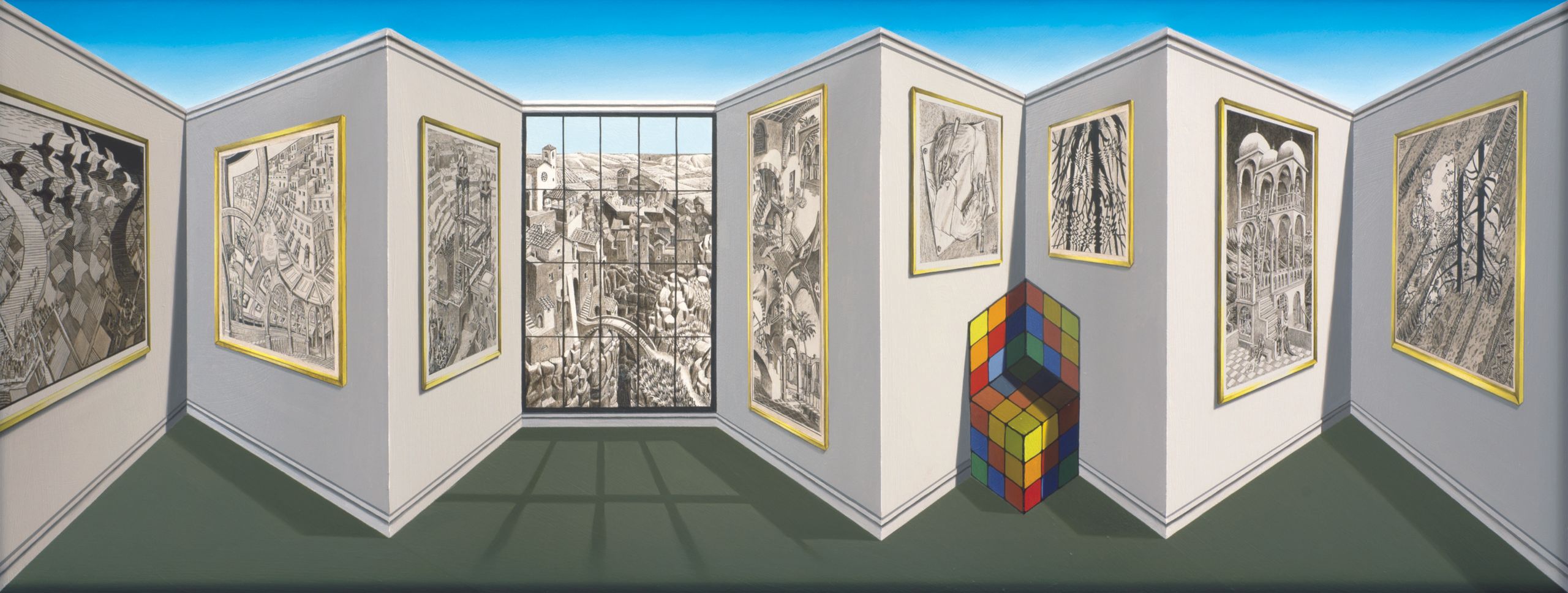

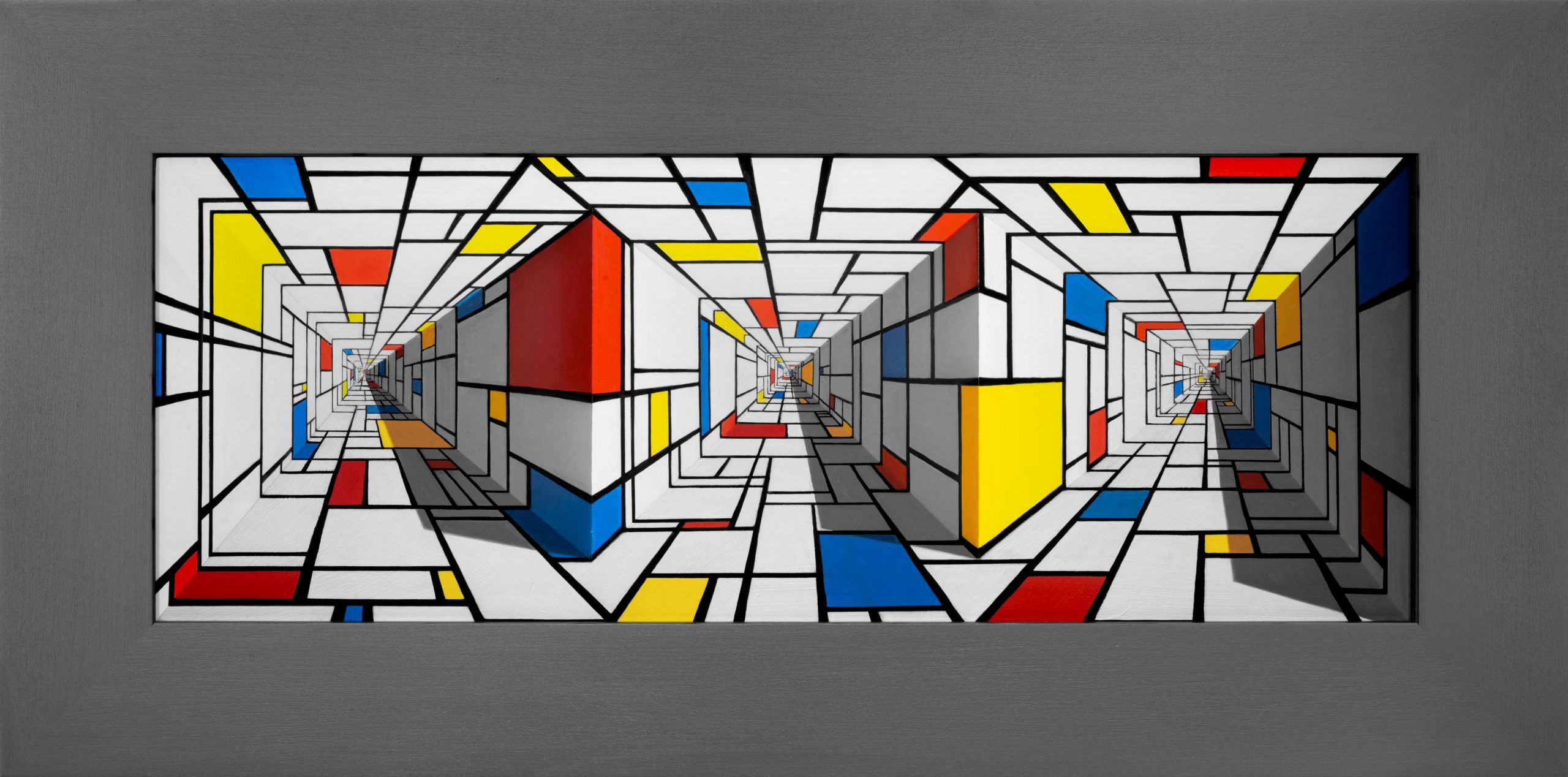

Referencing the prevailing art and literature of the last 100 years, Hughes’ work describes a world where the value of art is changing. Works of other 20th century artists hang on the walls within his paintings, and shift in dizzying reverse perspective – questioning our visual and bodily perception, redefining our understanding of artistic value, and reinforcing the importance of first-hand experiences of art. Hughes’ remarkably profound and unpretentious collection speaks to us through the humour which occurs when our presumptions surrounding material reality are tested, and his references within references, paintings within paintings, look to the changing functions and applications of art, ultimately declaring that ‘an artist, even when abused or modernised, still triumphs.’

What sort of role do you think humour plays in art? Your ‘reverspectives’ encourage a playfulness in your audience; could it be that humour is a way of easing a viewer into something more serious which you may be hoping to discuss?

The art of René Magritte and M.C. Escher (both born in the Low Countries in 1898) is humorous and witty. Magritte and Escher have excited and inspired me throughout my career. The surrealists were devoted to profound jokes. André Breton edited the first anthology of black humour. The alternative to humour in art is tragedy, which has been described as the raw material for humour. When you can understand the logic of the psychological and badly perceived errors of tragedy you can see it in a philosophical and comic way. In my reverspectives, I am discussing the presumptions and assumptions we make in experimenting our way in perception: guesswork is the basis of seeing. At the same time, I am putting forward a philosophy of flux and paradox that is more than narrow ‘realism’.

Even for a generation that is frequently subjected to perspective trickery and impossible geometry, viewing your paintings in the flesh is vital. Do you think it’s important that all art is viewed in person?

It is by far best to see my work in person because then you will experience the divergence between what your body tells you – proprioception – and what your eyes tell you. Your vision will notice that you seem to be moving to the left in one of my rooms or in front of my Venetian buildings, while your feet and knees tell you that you are going to the right. On film (which is so superior to still photography), the illusion is also exhibited, but without that personal feeling. It is often said that you should be in the presence of an artwork to fully get it – although I knew most of Magritte and Escher from books before I ever saw an actual painting or print by them – but that is particularly true of my work, and is a reason why it should be more visible in public museums and places.

Your reverspectives provide a physical experience for the viewer rather than the description of a concept. Do you think that this is an important characteristic of art – to show the viewer, without their need for any prior knowledge or explanation?

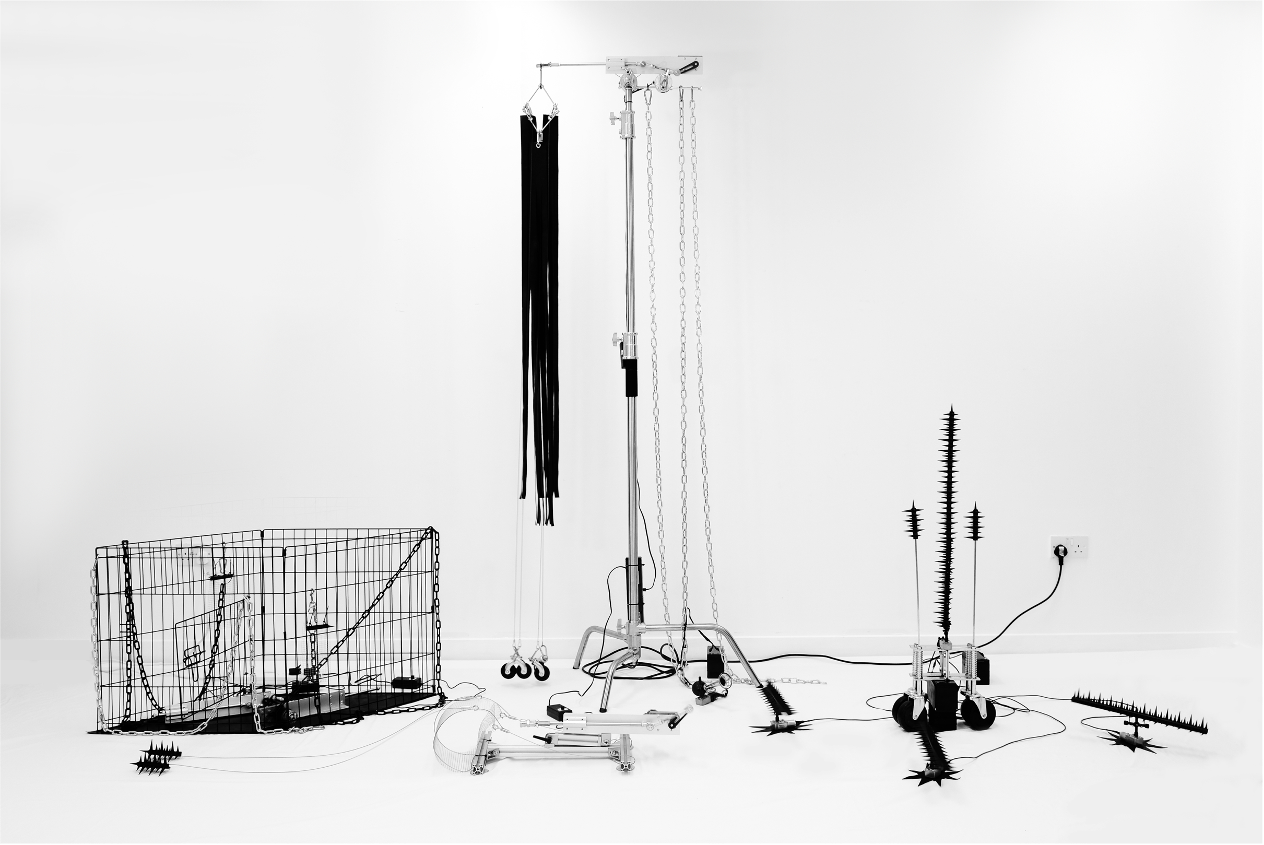

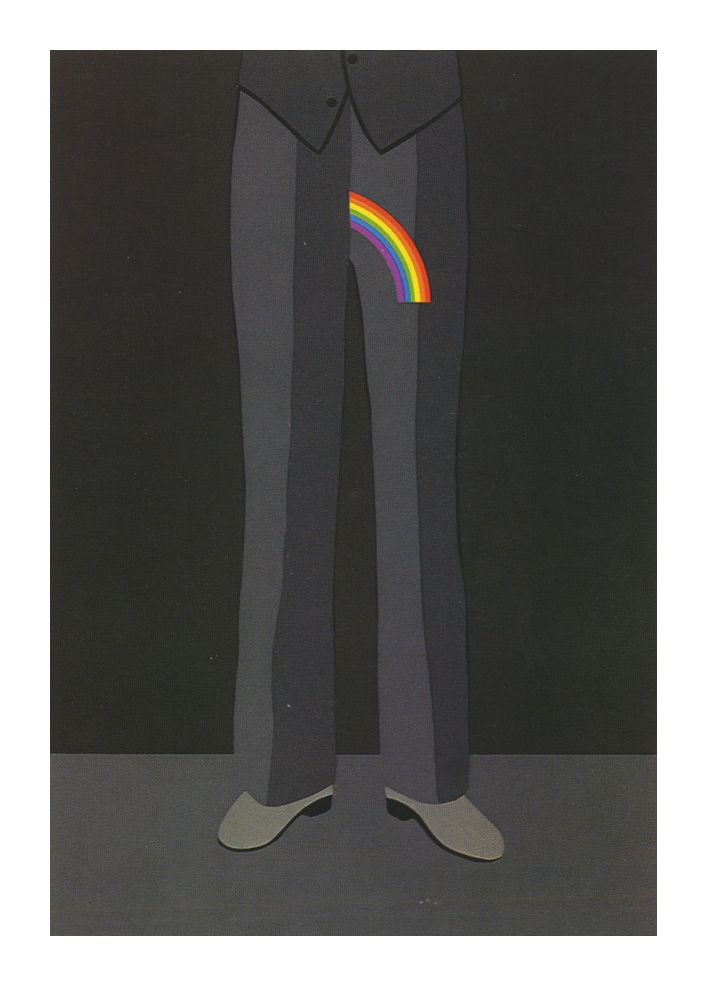

For my first four decades as an artist, I made pictures that were contradictions – solid spaces, or oxymoronic – grey rainbows, or paradoxical – vicious circles – and I was telling people about my philosophy of paradox and flux. But it is better to show than to tell, and more revealing to seduce the consumer into experiencing a completely contradictory illusion, which I now do in my reverspectives, without any explanation or foreknowledge. It used to be that ‘literary art’ was a no-no, that art should stand on its own two feet without any back-up from turgid prose or trite biographical stories about the creator. I like to think that my art is strong enough, well-enough designed, to wear its learning lightly and reveal itself without the aid of words.

As a writer and a visual artist, how do you find that these practices work together? Are there some things that you can only portray in words, or vice-versa? For example, regarding your earlier work, which utilises forced perspective, you discuss the idea of standing at the fictional point of infinity – the point at which the train tracks converge to a singular point on the horizon – and looking back. For me, this fascinating concept is difficult to convey visually.

I am an amateur writer, a theorist of other people’s creativity in my books about visual and verbal paradox and oxymoron. I am a student of rhetoric, wit, and imagination in the fields I am cultivating rather than the original creator I am in my art. The verbal arts are older established in understanding the techniques of literature than we are in the visual arts. To try to understand how better to create – without repeating what has already been done – I have codified and classified and anthologised the wit that interests me, and crucially, the visual techniques in areas of art that seem to me to be original and insightful. By making my train tracks come to the vanishing point physically I was taking perspective ‘literally’, an ancient rhetorical device.

Initially, you made your perspective works by eye. What kind of effect has computer geometry had on the way you work or conceive your work?

Photoshop came in about twenty years ago and it helped my art a lot. In the old days if I wanted to use buildings in a reverspective, they were necessarily simple and repetitive. But with Photoshop, I can also scan a Venetian palazzo and scan one of my perspectival trapezoids into Photoshop so that the computer accommodates the two together, and the resulting scan looks as if it had already been seen from that point of view. When I painted art on my reverspective gallery walls I tended to use Mondrian and Rothko, simple to do, with Photoshop I could use Vasarely and Lichtenstein and Wayne Thiebaud. And I can use Photoshop to try out ideas and make collage sketches and incorporate any imagery like graffiti and sculpture and furniture.

You frequently incorporate the work of others into your paintings. What is the driving force behind this? Your use of Mondrian and Rothko has a tongue-in-cheek nature to it; is there also a comment on appropriation hidden amongst these ideas?

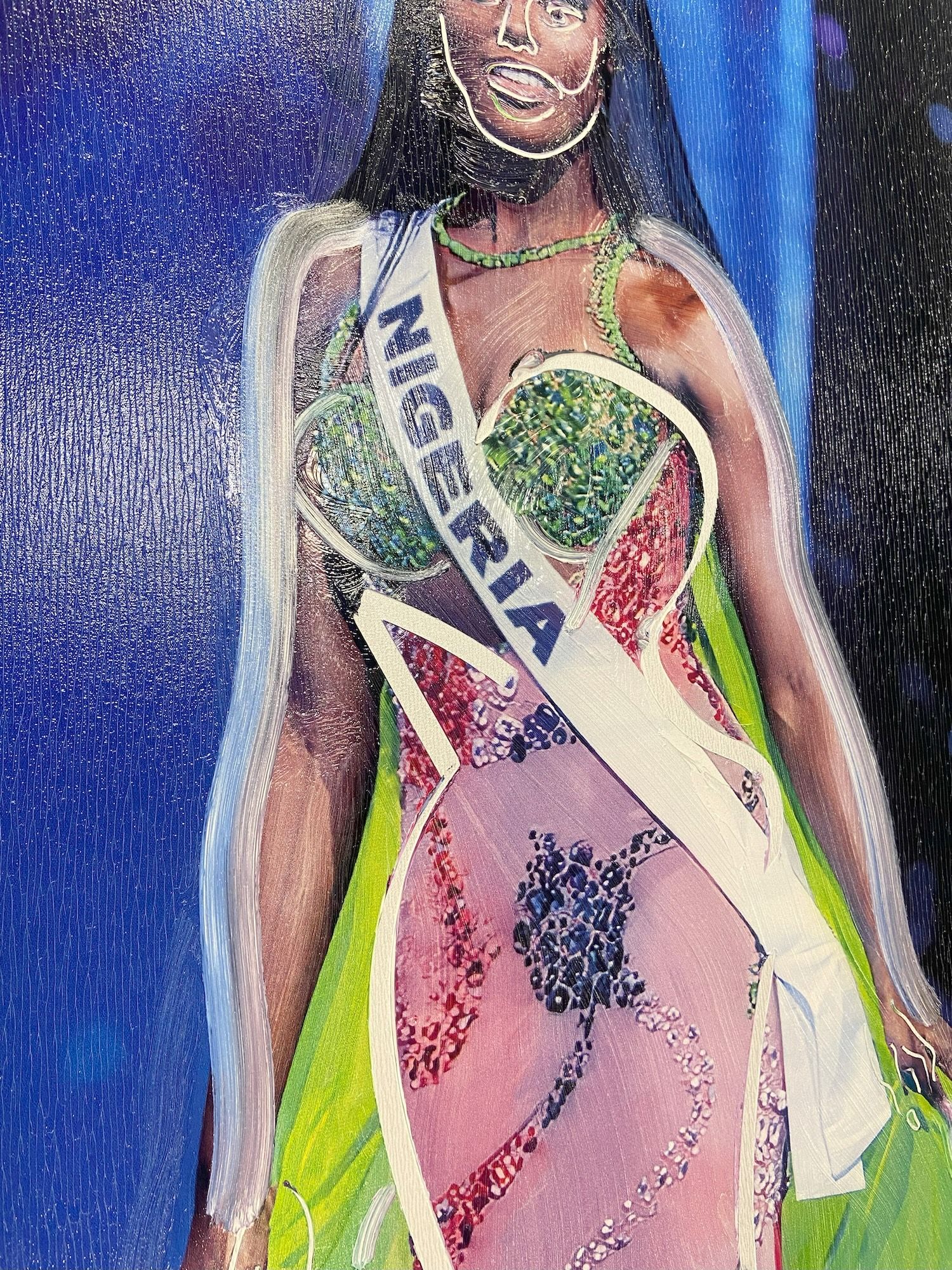

As a wall artist, a representer of spaces that end when they meet walls or buildings or windows and doors, I am always looking for things to put on my flat perspective surfaces. There is an irony in putting painters I do not admire – like Mondrian and Rothko – or ones I do – like Lichtenstein or Klee – into my pictures, homages or homilies. It is fun to put my own work on the walls too. The tongue is in the cheek. I am saying that a Magritte painted by me in a trapezoid, very small, is still a Magritte for a moment. Appropriation is the cant word for stealing or copying, by borrowing that art I think I am showing that an artist, even when abused or modernised, still triumphs.

Specifically, you talk of forcing revered Rothko paintings to obey an absurd perspective. Do you feel that art needs to be grounded in this way – to be made accessible?

I am an atheist of course; I am a rational being. I have been in the Rothko Chapel in Houston; I thought it was very feeble, it did not do anything for me. I would guess it does not do anything for anyone, although people can wish devoutly enough that it would or could. My work is accessible, it is made that way on purpose. I want people to have experiences that I can make for them. I would not just do it for myself, that would be selfish and self-centred and untruthful. Knowing what I know I want to share it with you and get you to smile in recognition.

Are there any artists that you have noticed who might be carrying on in the vein of what you have achieved?

I have about forty imitators – I castigate some of them on my website – disappointingly none of them have helped me develop reverspective art.

interview by Jason Roy

Patrick Hughes’ 60 Years of Art will be on exhibition at the Bel-Air Fine Art London, 105 New Bond St, Mayfair, London W1S 1DN, from 13th November – 15th December 2019.