It’s fair to say that the ENO’s new production of Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny isn’t your typical opera. For starters, it features a banging earworm of a song that has been covered by David Bowie, The Doors and Nina Simone. It talks about late-stage capitalism as if it was written today and not a century ago in Weimar-era Germany. And it may make you think twice about going (further) into debt.

We meet three fugitives on the run and in trouble. They find themselves stuck in the middle of a desert with limited options: leave everything behind and head into the open sand or wait for the cops to turn up. They settle on a third option and set up Mahagonny, a city that makes Las Vegas look like the Vatican. Everything and everyone is for sale and vices of all kinds – not least sex, booze and gambling – are catered for at every hour of the day and night.

Its pleasures are free for all to enjoy. That’s free as in speech, though, not as in beer and those who can’t pay their way face the city’s own flavour of justice. Into this den of delicious iniquity walk four hardened lumberjacks, their pockets filled with seven years’ salary. Only one walks out.

Created by composer Kurt Weill and playwright Bertolt Brecht, Rise and Fall inhabits the conventions of the opera house as well as the mood of the streets outside. Defying the origins of this classical art form, the pair never intended to write something to entertain the elites between meals but aimed for a work that the masses could relate to and revel in. Brecht wrote with deep antibourgeois feeling about the economic equalities in the 1920s; as rich industrialists ate well in their mansions, many outside went hungry in a ruined country reeling from defeat in the First World War. He wanted to shine a spotlight on his here and his now but instead created a masterpiece which speaks across time and space.

Weill, for his part, drew not from high society poster boys like Mozart and Verdi but instead infused the music with contemporary urban rhythms. “Alabama Song” (also known as “Whisky Bar”) is a classic of the twentieth century and sits amiably within a score that swipes left on tradition: jazz rubs shoulders with cabaret, ragtime elbows past hymn-like chorales, and the orchestra under André de Ridder plays along with supreme confidence. When it was first released, it raised a middle finger to the same wealthy patrons who saw opera houses as their sanctums. These days, classical purists will clutch their pearls. Everyone else may tap a foot.

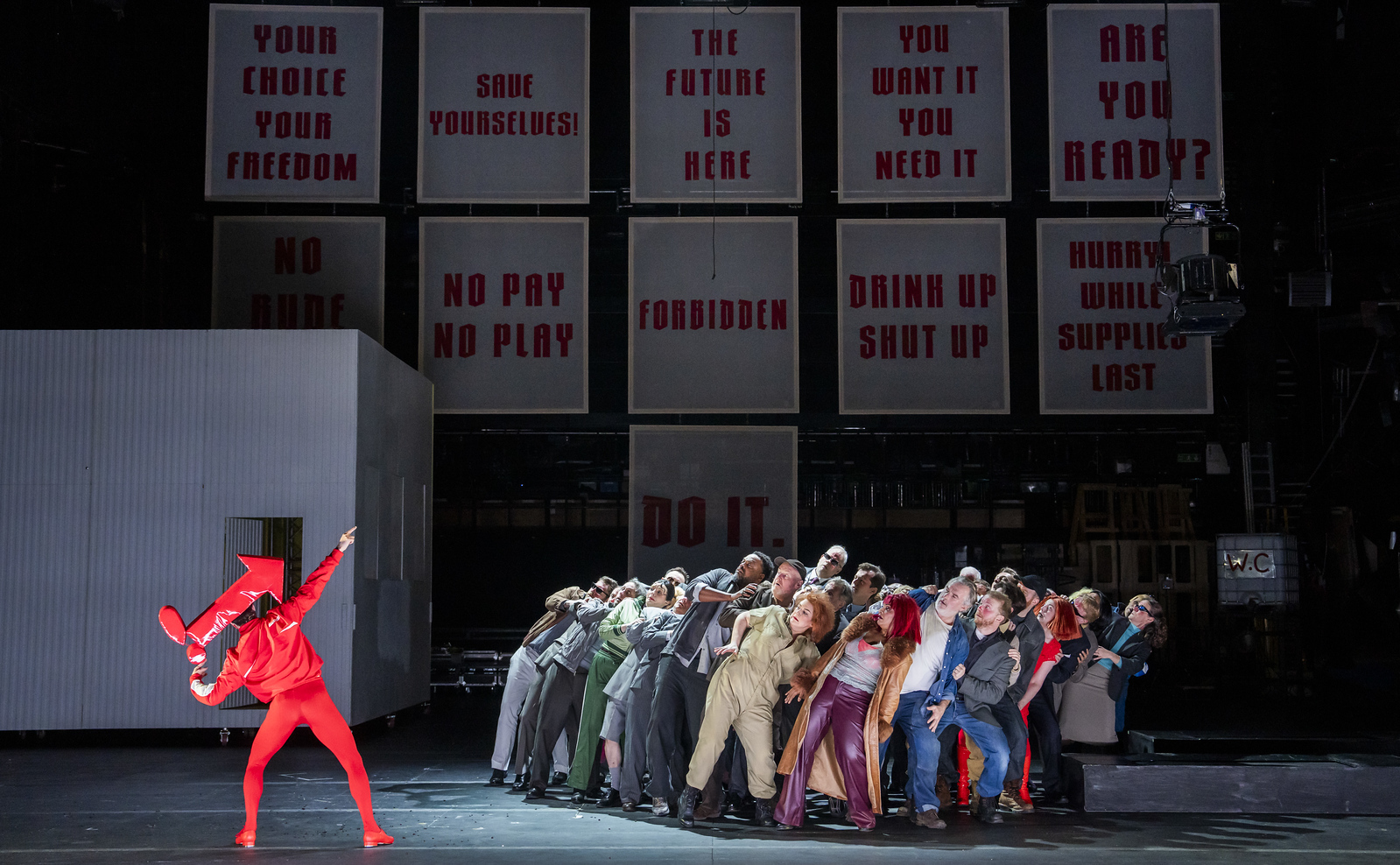

Director Jamie Manton leans into the contemporary parallels with all the enthusiasm of a seven-year-old on a sugar high. He vigorously illustrates life in a city where the citizens bounce between the buffet, the bar, the boxing ring and the bedroom. Mahagonny itself is rendered by designer Milla Clarke as a neon-splashed playground of debauchery and self-destruction. Her costumes scream late-night circus while DM Wood’s sepulchral lighting immerses us in a hazy vaudeville atmosphere. Lizzie Gee’s choreography suggests a society one bar fight short of complete collapse.

The cast approach the material with admirable commitment to moral ambiguity. Danielle de Niese’s cunning Jenny is less fallen woman, more market analyst of desire, calculating supply and demand with a high B-flat. Rosie Aldridge is magnificent as Widow Begbick, running the city like a start-up founder who has skim-read Adam Smith on their phone while binge-watching Succession. As the ill-fated Jimmy, Simon O’Neill brings a bright, almost heroic tenor to a man who commits Mahagonny’s worst crime: running out of money.

Jeremy Sams’s English translation is a little clunky at times but ensures that Brecht’s barbs land with contemporary clarity. When the citizens sing of eating, drinking, fighting and fucking as if these were constitutional rights, it feels uncomfortably familiar. The lumberjacks’ tragedies are rolled out with nary a note of sentimentality and harsh verbal brutality is only ever an aria away.

This work is rarely given a runout these days. In some ways, that is understandable. With its excoriation of capitalistic excesses and the depiction of leaders happy to look the other way for a sufficiently large bribe, we can’t see this appearing at – taking one random example – the Trump Kennedy Centre (at least not without some judicious redactions).

That’s a shame as there is real genius in both the original work and this ENO staging. Manton refuses to treat Rise And Fall as a museum piece about Weimar decadence. Instead, he digs deep to make it feel like tomorrow’s headlines. In the end, it is less an opera than an economic forecast set to syncopation. It argues that, wherever pleasure becomes policy and Mammon is the mayor, collapse is not a tragedy. It is a business model. This is an important and relevant production that reaches beyond the Twenties into our modern hearts of darkness.

Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny continues at London Coliseum until 20 February.

Tickets and more information from http://www.eno.org

Words Franco Milazzo

Photography Tristram Kenton