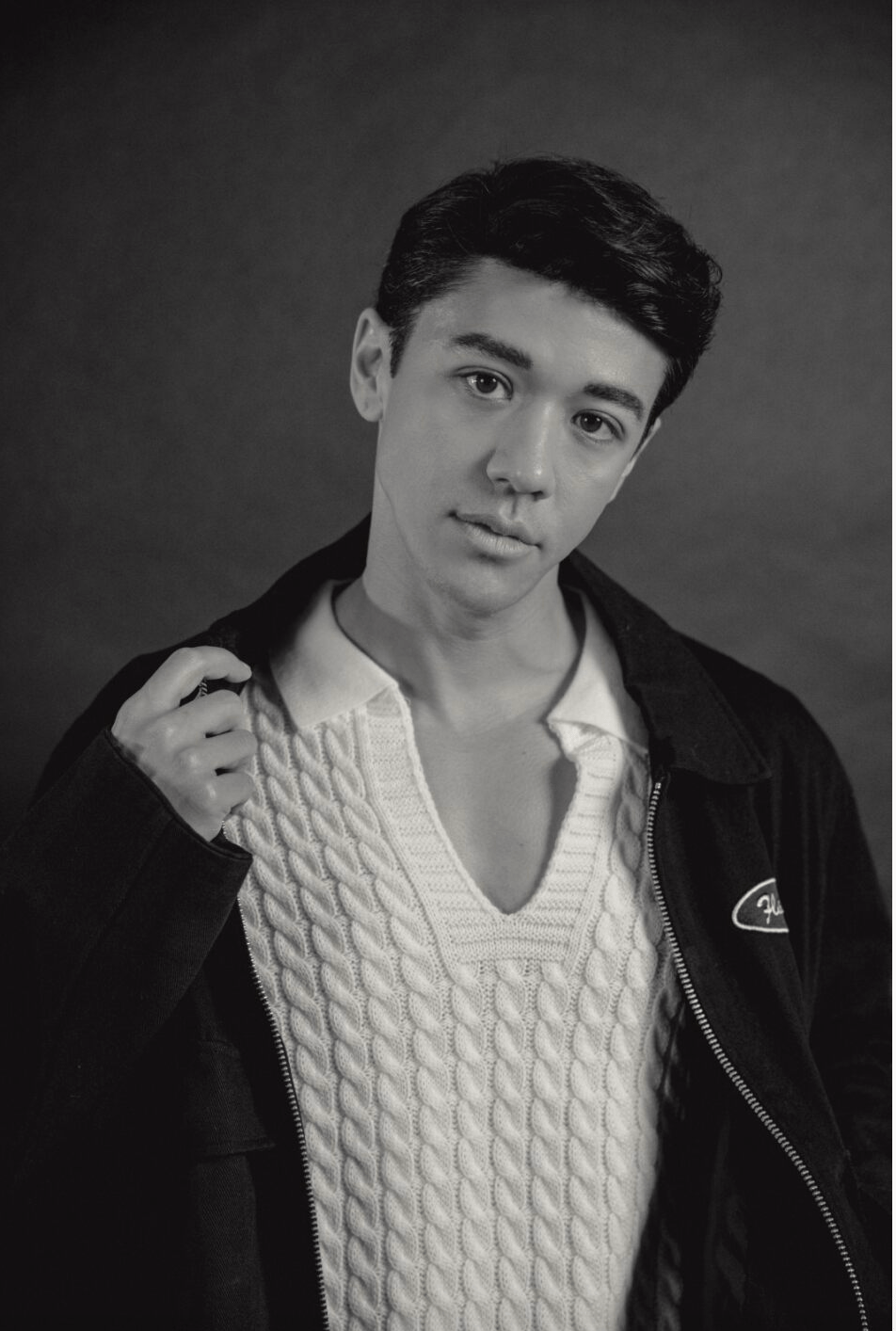

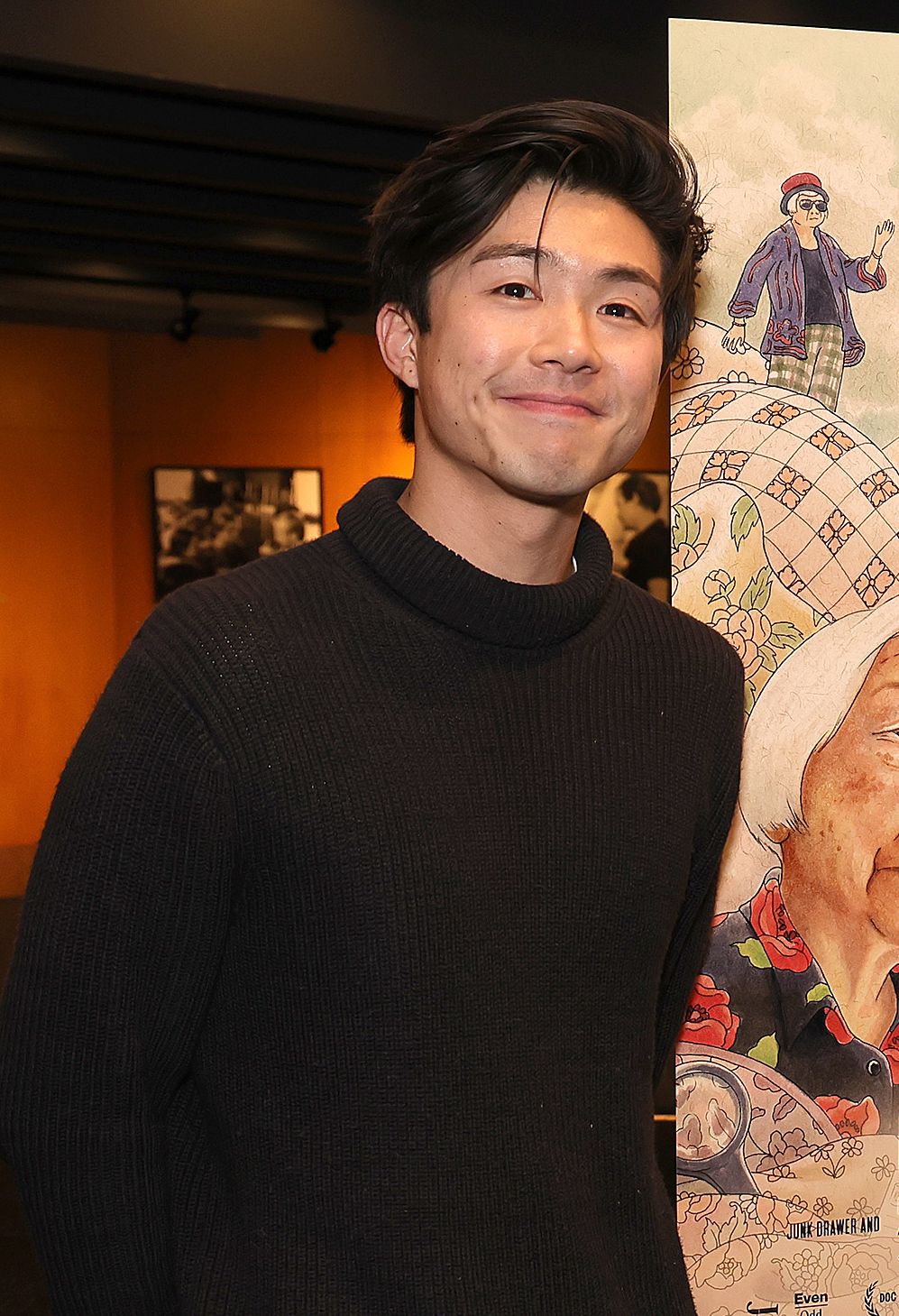

Sean Wang

Sean Wang’s Oscar-nominated short film Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó introduced swathes of strangers to two of the closest people in his life: his grandmothers. The pair live together in the Bay Area, and have garnered a following of devoted – for lack of a better word – randos.

For Wang, there’s no possessiveness to his relationship with his grandmothers. “It would be weird if they were allergic to the attention but they love it. I think they’re so thrilled that people get to see the movie, see them; and that was so much of why we made it, to try to show a version of them and a version of people like them that I think society and culture often doesn’t see, or overlooks,” he says over Zoom.

His goal was to show the full remit of their lives. “All the silliness, the joy, the slapstick, and the humour but also the very human sadness, loneliness, regret. The fact that they get to share that with the world, they’re so thrilled.”

They are, in Wang’s words, “proper celebrities.” At the Oscars luncheon, “They were on point, waving to people on the red carpet.”

There are many things to draw a viewer into the unique world of Nǎi Nai and Wài Pó. For one, how close they are, for being in-laws. But for Wang, this uniqueness wasn’t something that he realised he had. “Sometimes when you are making stuff that is personal or even autobiographical in a sense, literally turning a lens on your own family or your given circumstances, you don’t even realise that it is a unique situation until you’re kind of zooming out, and your friends saying ‘that’s so unique, that your grandmothers live together and get along.'”

As far as the actual making of the movie goes, “it wasn’t necessarily that I saw them and saw a unique perspective, it was more going back to the personal — I wanted to capture them and their relationship and what it meant to me, as opposed to me being like ‘oh look how unique this is,’ right? Ultimately, I think, having collaborators and producers who can be like, ‘Wait, they sleep in the same bed?’ It’s already a unique relationship but that’s such a unique detail. And I’m like, ‘Oh, really?'”

As we are drawn into the multitudes of their lives, we see glimpses into the inherent tensions of their specific stories. One pivotal moment is when Nǎi Nai describes how the newspaper keeps her alive. And yet, at the same time reveals they haven’t gone to the market in a year because what they read in the paper is so scary.

Casual viewers may not know why, because Wang didn’t want to be too “on the nose” about it, but the film was shot in the spring of 2021. “So it was twofold,” Wang says. “It was COVID, and with COVID came a spike of anti-Asian sentiment, Asian hate crimes that were targeted, especially, towards elderly people in our communities, people like my grandmothers, especially in the Bay Area, where I’m from.

“So it really felt like these violent things that were happening to people like them were happening right outside. That was a very strange, angry experience.”

This subtle juxtaposition of “the reality, the very grounded, day-to-day of what their lives were like, with the joy that I felt with them on a day-to-day basis” allows the film to feel like a true fly-on-the-wall experience.

It’s a balance Wang has been thinking about a lot recently. “At the end of the day, I’m their grandson, but with this movie I wanted to also get to know them on a more human level. I wanted to understand their history, their past, their story. I wanted to know who they were before they were my family. I wanted to know what their lives were like, the pains of their childhood.”

That understanding, however, goes two ways. “It was important for me to level with them in a human-to-human way of: one day you’re not going to be on this earth anymore. I’m going to grow older and I’m going to have children and I want them to know you guys in a very complex, three-dimensional way. If you don’t tell us the pains and the sadness that you also went through, that’s how you lose family history. That’s how you lose culture. And so I had to be vulnerable on that level with them too, and be open to hearing all of that.”

The camerawork moves in such a way that at times you feel yourself a child – a sort of regression therapy – with low angles looking up at Nǎi Nai and Wài Pó’s expressive faces looming larger than life. It was, perhaps, a happy accident. Wang smiles, almost surprised, when asked if it was a purposeful choice. He pauses. “I’ll say… yes. I’ll say yes,” he laughs.

In the present moment, his Oscar nomination has… sort of, not really, but kind of, shifted how he views his career. “It’s a big existential question,” he says. “I don’t know… Yes and no. I also just finished my first feature film Dìdi, which premiered at Sundance, and that experience has kind of overlapped with this Oscar experience.”

“I’m in this period in my life now where I am getting asked that question, and when I think about the next 10 years, next five years… thinking that far is really terrifying for me.”

To get to an answer about his future, Wang comes back to the present. “I think what was so special about this movie and the feature film, both of them are so deeply personal and in some ways are autobiographical.

“The only thing I really hope for with what’s next is that I don’t want to only make movies like these, that are so directly linked — like a one-to-one — with my life. I don’t want to continue to do that for the rest of my career. I hope that whatever I do next, I can really sink my teeth into. Even if it’s like a movie set in space, it can feel just as personal as movies like these.”

The maxim ‘write what you know’ inherently poses a tension particularly for storytellers from ethnic minority backgrounds. There is a prevailing expectation, to a certain degree, to consistently tell stories from that personal point of view. Whether or not this was a preoccupation for Wang gives him pause. Literally.

This question is something that Wang thinks about a lot, too. “I think people are going to label your movies however they want to label them.”

With Wang’s feature film Dìdi, which is loosely based on his childhood, he was “very cognizant of not wanting to make an Asian American movie. I wanted to make a movie about an Asian American. To me, those two things are separate.”

“For me, what’s true is that anytime I’ve tried to make something directly explored what I think those ‘themes’ should explore, it never worked. It always falls flat. It never feels honest. It feels like I’m falling into what the canon of what those [kinds of] movies have already done. Because they’ve been defined.

“Anytime I ignored that and looked more inward and just asked myself, ‘How do I make this more personal?’ it checks those boxes anyway because I come from that community. I come from that background.”

At a recent screening of Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó, the person who introduced the film said they were proud that ‘it was so unapologetically Asian,’ Wang says. “And it is, but you know, it’s also unapologetically Asian because my grandmothers are Asian. And I’m Asian. So by making things that feel personal, and that come from that distinct point of view, it’s already there. It’s in the DNA of the movie. It’s in every choice that I make.”

Perhaps more importantly, it’s the idea of an expectation — any expectation at all — that Wang rebuffs. “Unless they come from you, they’re just noise. That’s the hard part about all of this, about the spotlight. I’m very grateful for the spotlight, but with that comes a little bit more noise. And I think the challenge is to shut out the noise.”

But what does that look like in practice? “Don’t follow the things that are shiny and attention-grabbing because of who’s attached or whatever. Really look inside yourself and ask yourself, what interests you. It doesn’t have to be autobiographical. And personal doesn’t mean autobiographical. I think of the emotions I’m interested in exploring and the container is a story that has that. It doesn’t have to be about the communities that [you come from]. Look at Ang Lee for example, who can tell stories that are so deep and human, and he’s able to find his way in.”

It comes back to the happy accident, or deliberate choice, of the camera angles. That childlike universality of looking up at an adult. It puts you back into that moment that almost anyone – if they’re fortunate of course – can relate to — looking up at a grandmother who loves you.

For Wang, that’s the “beating heart” of a story. “The most meaningful stories are the ones that you have the most intimate access to. That is the thing I’m forcing myself to be conscious of. Reminding myself of. Take the meetings, read the scripts, but ultimately ask yourself ‘Are you interested in this because you can find your way in? Is there a beating heart underneath it?’ When you go to sleep and you can’t stop thinking about it because it questions your worldview, or it’s challenging you about your perception of life and death, and these big questions that I think we think about as human beings.”

If the Edgar Allen Poe-like sensation of being consumed like this gives you an anxiety attack, you wouldn’t be alone. But for Wang, there’s a sound reason that drives this need: “Because making stuff takes years and years and years. And I think: if I’m going to do something I need to make sure that it’s challenging me just as much as I am excited about it. It’s keeping me going, it’s making me grow as a human at the same time as I’m making a movie.”

Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó is streaming now on Disney+.

Interview Gabriella Geisinger