“Listening to the voices of others, responding to actions in the external world, and positioning myself as a mirror that faithfully reflects reality—or as a container that absorbs multiple voices.”

This is how artist Shuqin Huang describes her artistic methodology. She refers to this approach as “reflection.”

For Huang, art does not emerge from pure imagination, but from sustained attentiveness to reality and an active response to it. Can feedback generate alternative perspectives? Can it create subtle yet tangible ripples within a world people have grown accustomed to? These questions form the foundation of her ongoing artistic practice.

Questioning the ‘Normal’

Huang remains deeply skeptical of what society tends to accept as “rules,” “habits,” or “unwritten norms.” What appears stable and reasonable on the surface is, in her view, precisely what deserves closer scrutiny.

She once compared everyday life to a machine operating along a predetermined trace, her interest lies in locating the smallest cracks within that system—those moments of “abnormality” hidden inside what is widely perceived as normal.

“If we don’t treat something seriously as a question,” she explains, “it easily gets covered up by phrases like ‘everyone lives this way’ or ‘just endure it and move on.’ But once something is consciously acknowledged and articulated—much like Freud’s idea of bringing the unconscious into awareness—the symptom itself can begin to loosen.”

Huang’s practice begins with these overlooked moments in daily life. Through artistic intervention, she enlarges, records, and responds to them.

Presence, Performance, and Weaving

To practice reflection, Huang insists that the artist must be physically present—embedded within the situation and in direct relation to others. In her work, performance becomes a crucial medium for establishing this connection.

Through performance, she overlays fictional narrative space with the real space occupied by the audience. Viewers are no longer passive observers; they are drawn into the unfolding narrative, filling its gaps with their own experiences. As bodies move through space, individual trajectories intersect, collide, and intertwine, gradually forming a network of relations.

Huang describes this process as “weaving”—a mode of collective formation generated through presence, movement, and perception. For her, it is a way of placing personal experience into a shared public context.

Feminist Experience and Invisible Cracks

Among all the cracks embedded in everyday life, female experience is a central concern in Huang’s work. As a woman, she has become acutely aware of the subtle fractures that demand attention yet are routinely ignored—sometimes even by women themselves, who unconsciously choose silence and endurance.

Her reflection on female identity stems from her own lived experiences, family dynamics, and intimate relationships. Since 2018, her artistic practice has consistently focused on the “invisible violence” women face within social power structures. These conditions are often too subtle to articulate clearly, yet they exert a profound influence over women’s lives.

As feminist scholar Chizuko Ueno writes in Misogyny, misogyny is not hatred toward a specific woman, but a structural bias directed at all women. Huang amplifies these often unspoken biases to an uncomfortable degree, forcing viewers to confront their presence.

In her performance work Fantasy Land, she stages the narrative within a private bedroom—a space associated with intimacy and vulnerability. Through improvised performance and fictional scenarios, the work exposes power imbalances within heterosexual relationships and the emotional tensions that arise from them.

The Witch: Fear, Deviation, and Power

In recent years, the figure of the witch has become a key conceptual thread in Huang’s work. She is drawn to the word’s ambiguity and tension: witches are women who provoke fear—especially among men—women perceived as dangerous, uncontrollable, and resistant to social discipline.

Historically, during the height of European witch hunts, women who lived alone, midwives who assisted with childbirth or abortion, and women who practiced herbal healing were frequently labeled as witches. Their so-called crimes were not acts of evil, but rather their refusal—or inability—to conform to patriarchal expectations of dependency and wifehood.

In her work The High Priestess, Huang draws inspiration from tarot symbolism and Western astrology to explore the duality of female identity: the wise and pure priestess on one side, and Lilith—the embodiment of desire and ambition—on the other. In Greek mythology, Medusa was once a priestess in Athena’s temple before being cast out and demonized after experiencing sexual violence.

“Good and evil are not opposites,” Huang reflects. “The so-called evil Medusa represents an inner power that every woman has yet to fully uncover.”

Witch Bathroom: Alienation in a Private Space

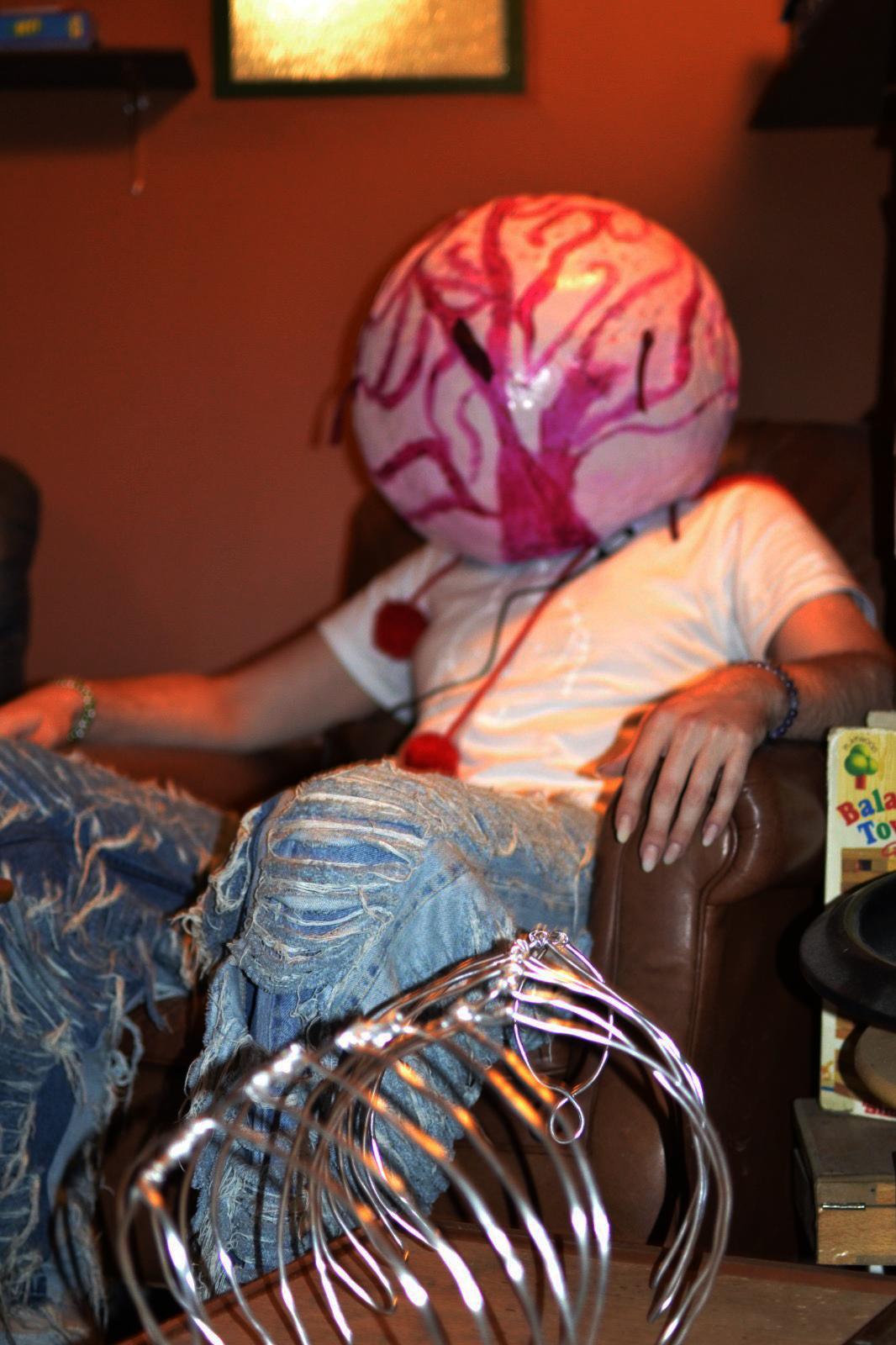

In 2024, Huang presented her first dual exhibition in Beijing, introducing the Witch Bathroom series. The exhibition space was deliberately dimmed, with black wooden floors over which oversized, yarn-covered domestic objects sprawled in a state of subtle distortion and entanglement.

She chose the bathroom as the conceptual foundation of the work because of its intimate nature. “The bathroom is a completely safe space,” she explains. “It’s where people can be honest with themselves and release emotions that aren’t accepted in public.”

Huang recalls reading an interview with a mother of three who said the only time she could be alone during the day was when she locked herself in the bathroom. “I believe women have a particularly deep relationship with this space,” Huang adds.

Within this constructed bathroom, everyday objects—bathtubs, sinks, soap, combs—are recreated at a 1:1 scale using yarn. The familiarity becomes strange. The soft material introduces a sense of discomfort and alienation, prompting viewers to feel the tension embedded within domestic and private spaces.

Reflection as Action

Through performance, presence, and reflection, Huang Shuqin continually situates personal experience within a broader social framework. Rather than offering solutions, she presents cracks—allowing them to be seen, felt, and discussed.

In her work, to respond is already to act. And it is precisely through these small yet sustained acts of response that the possibility of change begins to emerge.

By James Mitchell

Top image credit – Untitled, 2020. Live installation, Shanghai, China.