In 1983, Simon Parkes bought Brixton Academy for just £1. He was 23, full of ideas, and totally unqualified. But what he lacked in credentials, he made up for with instinct, nerve, and a knack for getting people to say yes. Over the next two decades, the Academy became one of the most iconic venues in the UK – hosting The Clash, The Smiths, N.W.A, Nirvana, and more.

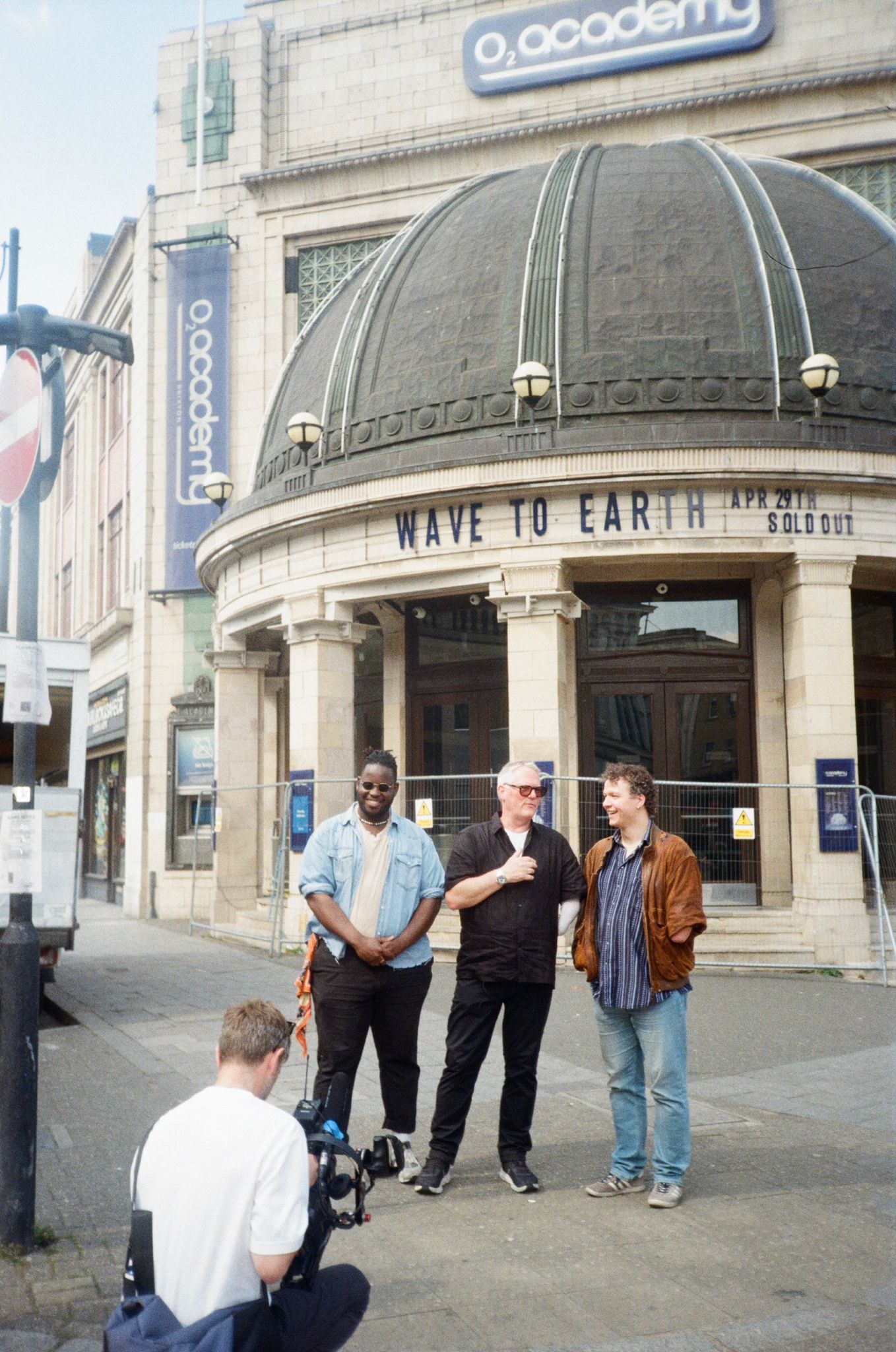

It stood at the crossroads of music, politics, and community during some of the most turbulent years in recent British history. Parkes told that story in his memoir Live at the Academy, and now it’s the basis of a new play, Brixton Calling, by writer Alex Urwin, with Max Runham starring as Simon, and Tendai Humphrey Sitima as Johnny Lawes, his best friend and business partner. In this interview, Parkes reflects on his life, the legacy of the venue, and why bringing it to the stage – with all its chaos, energy, and defiance – feels like the perfect encore.

So you were 23, and you bought the Academy for a pound. That’s amazing. Tell me about it.

Technically I paid a pound – just to make the contract binding. What I really offered was a 10-year exclusive beer deal.

I’d just finished studying accountancy and law at South Bank Poly – hated it, but it gave me a solid grounding in basic law and finance, which served me well later. I knew I wanted to work in music, and I saw the Academy was on the market. It was owned by Watney Coombe Reid, a brewery, and they wanted £120,000 – which I didn’t have.

But I called them anyway. This was just after the Brixton riots, and the area was rough – no one wanted the place. I pitched a simple plan: concerts, beer – theirs, good times. They thought I was taking the piss. But they saw I was serious, and agreed – with the caveat that £10 came off the £120k for every barrel I sold. In the end, I shifted £7–8 million worth of beer. They were delighted. Later they even lent me £1 million to refurbish the venue. No bank would have touched me – not at 23, not in Brixton.

I imagine that kind of instinct – being able to read people and move fast – must’ve served you well during your time running the Academy.

Definitely. One of the best examples is the Nirvana situation.

I was planning a new festival with my mate Dave McLean – it later became the V Festival. We had Nirvana headlining, with Green Day, Smashing Pumpkins, Beastie Boys… huge lineup. At the same time, we had four sold-out Nirvana shows at the Academy.

Then Kurt Cobain killed himself – and because it was suicide, it wasn’t insured. I’d already spent the money. I was fucked.

My head of security – total memorabilia nut – asked if the tickets might be worth something. I dismissed it. But later, Radio 1 rang. Joe Wiley asked about the mood in Brixton, and I just blagged it. I said people were calling to buy tickets as memorabilia. That line got picked up everywhere. Suddenly, we had a market. We put ads in NME and Loot – ‘Wanted: Nirvana tickets – £50.’ 85% of people never asked for refunds. The rest, I resold.

It saved me. But the agent panicked and flipped the rest of the lineup to Reading. So if you look at Reading ’96 – that was my festival. I was fucking livid. It was a turning point. I didn’t want to work with people like that anymore.

What kind of state was the place in when you first walked in?

It was a mess – damp, dark, full of junk. Rank had been using it to store spare cinema seats. But the structure had real charm: a huge stage, grand proscenium arch, part of a rare group of ‘atmospheric’ theatre cinemas built in the late ’20s.

The clincher for me was the sloping floor – wherever you stood, you could see the stage. And no seats. I was into mosh pits, movement, madness – not sitting down. I knew straight away it could be the perfect live venue. Even if no one else did.

What kind of reaction did you get, being 23 and taking on something this massive?

Mostly: ‘Are you mad?’ Brixton had a rough reputation. People thought it was dangerous – that no one would come. When I called agents, they laughed. One said I’d never get a rock band to play there. That first year, I put on 19 gigs – all reggae. No one else would book them.

The turning point was five nights of The Clash for Arthur Scargill’s Christmas fundraiser – raising money for miners’ kids. I’d played rugby with colliery teams in South Yorkshire, so I felt for those communities. When they opened with London Calling, the place exploded. That’s when I knew the venue had power.

After that, we became a hub for artists with something to say – The Smiths’ final gig, Artists Against Apartheid, Public Enemy, N.W.A, Paul Weller. The ’80s were full of tension, and Brixton was right in it. We weren’t trying to be political – we were just there.

That’s what excites me about the play. It captures that moment where music and politics collided, and everything felt like it was shifting.

Have you seen much of the show coming together yet?

Yeah, I’m heading into London in about 10 days to sit in on some rehearsals, and I’ll be back in early July for the workshop stage. But I’ve already seen some clips. The two guys – Max Runham, who’s playing me, and Tendai Humphrey Sitima, who’s playing Johnny – are amazing. I thought they were best mates when I met them. Turns out they’d just met.

Max has only got one arm, like me – and when I saw that, I was gobsmacked. I’d always imagined that if someone ever made a film, they’d just cast anyone and CGI the arm. But here’s Max, practically identical, and he plays guitar – something I’ve always wanted to do. He’s a phenomenal musician and actor. Honestly, I’m rooting for them more than for me. They’re proper characters. If this launches them into something big, brilliant.

So, can you tell me about the other main character in the play?

The other main character is Johnny Lawes – and the way we met says a lot. He was a Rastafarian who used to knock on the Academy’s back door saying, ‘Give us a job.’ I liked him. He had something about him. Eventually I said, ‘What can you do for me?’ He goes, ‘You tell me.’ So I said, ‘Get me UB40.’ He reckoned he knew the trumpet player. I told him if he pulled it off, he’d have a job. Then he goes, ‘They live in Birmingham,’ and I’m like, ‘Yeah, I know.’ ‘Well, I need a car.’ So I gave him mine. Didn’t know his surname. Gave him the keys, some petrol money, and off he went. Three days passed – no mobile phones – and I started thinking I was insane. But he came back with a signed contract. Got the job, and we became best mates.

He was also a bridge between me and the local community. I’d grown up in rural Lincolnshire, with no Black population at all, so I’d never been exposed to what he was up against. I wasn’t experiencing the racism – but I saw it, constantly, because I was with him. Cabs wouldn’t stop. We’d get turned away from restaurants even when there were empty tables. He stayed calm – I’d get furious. It was a real education.

And how did the play first come about?

Alex, the writer, got my number from the publisher of Live at the Brixton Academy and just kept emailing. I’m not a big theatre guy – I go, enjoy it, say I’ll go more often, then don’t. But I liked his tenacity. So I said, ‘I’ll be in Brixton – let’s meet.’ We hit it off. He’s a character, in the best way. I told him, ‘Go see what you can make happen.’ No contract, no faff. Just a handshake. Within weeks he’d booked Southwark Playhouse, brought in Bronagh – a highly acclaimed director – and Diana, an award-winning PR. Got Arts Council funding. I thought, ‘Bloody hell, this guy’s for real.’

Eventually we sorted the paperwork, but I’ve kept out of the way. This isn’t my world. They clearly know what they’re doing. They send me clips from rehearsals – the energy’s great, the vibe’s right. It’s got all the ingredients.

How does it feel, seeing your life played out on stage?

Weird. I’ve never courted publicity for myself – just for the Academy. This is different. It’s personal. I don’t love the sound of my own voice. But I trust the team. From what I’ve seen, it’s clever. Max and Tendai play multiple characters, narrate the story, and play the music. It’s got that scrappy theatrical energy that suits the story.

I think it’ll capture the spirit of the time – that buzz. The ’80s and ’90s were wild, politically and musically. If you weren’t there, it’s hard to describe, but they’re finding a way to show it. And yeah, I’m excited. Nervous too, because it’s personal. But mostly excited. It was a free-spirited era. I worry a bit about today – feels like everything’s more regulated now. I never stuck to the rules. I was a nightmare at school. But that freedom, that instinct – that’s what made it all possible.

Did you get to sign off on the script, or was it more hands-off once things were rolling?

Technically, yeah – there’s a clause in the contract that gives me the right to object to anything if I think it crosses a line or might upset someone. But honestly, we’re all on the same page. I’m dyslexic as hell, so reading plays isn’t really my thing, and I’m happy to leave the words to the professionals. Unless something really jars, I’m not getting involved. I think I’d ruin it if I tried.

It’s an exciting project – and that era of music, from reggae to rock to hip-hop to rave, was massive. It didn’t just change the sound of the country – it changed the culture. Especially in London. That whole shift was seismic, and it’s a big part of what the show’s capturing. So no, I haven’t tried to micromanage it. They know what they’re doing. I trust them.

You mentioned earlier the racism you witnessed through your friendship with Johnny. Do you think things have changed since then?

Yeah – massively. My wife’s half Jamaican, so I’m still tuned in. In London and other big cities, people don’t really blink anymore. But I’m not sure the whole country’s there yet. I’ve still got a radar for it.

Back in the ’80s, the media were a huge part of the problem. Brixton got called ‘Murder Mile,’ even though most of the trouble was in Stockwell or Clapham. One copper told me 100 lads were behind nearly all the crime, but the press painted it like the whole area was dangerous. The reality was different. After gigs, I’d see white kids off their heads outside The Fridge or Mass, while the Black community were up early, dressed sharp, heading to church. The media never showed that.

Johnny helped me break in locally. There was suspicion – fair enough – but he vouched for me. These were solid, resilient people. But the racism was real. Once, cops dragged me from a car with Johnny. Comedy moment when they couldn’t cuff me – just the one arm – but still called me an ‘N-lover.’ It’s not like that now. Not perfect. But better.

It must be incredible for Max to get to play you – and for audiences to see that kind of representation.

Yeah – he’s such a nice guy. Full of energy, really lovely. I think he was a bit nervous to meet me at first, but honestly, I was in awe of him. I’ve always loved music – I used to play trumpet, the only thing I could manage – and my gran once left me a piano, not really thinking through the one-arm situation.

Watching Max play guitar is mind-blowing. He tapes his small fingers up like plectrums and just goes for it. I’ve asked him for lessons – I’ve always wanted to learn. But yeah, it’s wild. He’s a phenomenal musician and a brilliant actor. And Tendai, who plays Johnny, is just as impressive. You warm to both of them straight away. The chemistry between them is proper – it feels like they’ve known each other for years. That connection reminds me a lot of me and Johnny – we were a real team. I really hope this launches both their careers. They deserve it.

So your story’s been a book, now it’s a play – do you see it going anywhere else?

Yeah – I was chatting with an old mate of mine, Dave McLean, one of my old business partners. He’s working on a film project at the moment, and about a third of it’s about me, so there’s that.

Sounds like this whole project has reawakened something for you.

Yeah, it really has. I’ve sort of retired now – or was trying to – but all this has stirred my enthusiasm back up. I do miss the industry. It was tough and stressful, but exciting too.

And the play… there’s just a real buzz about it. Everyone involved is brilliant, and apparently ticket sales are already ahead of expectations, even before a proper marketing push. The associate producer, Katy Lipson, has taken shows to the West End, so who knows what’s possible? My fingers are crossed for them. A great vibe, great cast, great team, and a lot of heart. I’m excited to see where it goes.

Has Max been trying to capture the way you speak at all? Is he doing an impression of you?

A little bit. I saw a clip the other day where he’s trying on a hint of a northern accent – but I don’t really have one. He’s a South London lad, so there’s a bit of a twinge in there, but it’s not quite my voice.

I’ll be with them a lot in the three weeks leading up to opening night – probably dropping in most days – so I imagine he’ll pick up some little tweaks then. He’s a clever guy. Both of them are. And he’s better looking than me, that’s for sure.

Now, or back in the day?

Definitely now! He’s a good-looking lad – and a really nice bloke. I’m excited about the whole thing. That era, the ’80s into the ’90s, was massive. Culturally, politically, musically – everything was shifting. One minute I was putting on fundraisers for political causes, the next I was having lunch with Thatcher to talk about what the government could do for Brixton. The Academy played a big role in the area’s regeneration – it brought people in, gave the local economy a lift.

But I do think it’s gone too far. It’s over-gentrified. The people who carried Brixton through its toughest times were priced out. The soul’s been diluted. Someone sent me a clip of Dr Dre and Snoop talking about their first UK gig – it was at the Academy. They loved it. It was alive back then – buzzing. Now it’s all coffee shops and flats you can’t afford.

This play captures that wild energy. It was free-spirited and bold – we worked with the council, with the police, even got N.W.A to take down their ‘F*** the Police’ posters after a call from the local commander. People were more open, more willing to act. I came from privilege – private school, all that – but Brixton opened my eyes. I saw injustice up close. This show’s got teeth and heart. I’m nervous, yeah, but mostly I can’t wait to see it land.

What do you think 23-year-old Simon would make of all this?

Judging by my kids – they’re in their early twenties – I reckon he’d love it. They’re more into the music of the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s than what’s out now. I think young audiences will really connect with the soundtrack, and with the story too. I wasn’t some genius – just full of energy and naïve enough to leap in. That probably saved me. I remember getting threatened by some serious gangsters in Riddles – I didn’t have a clue what the danger was. Looked the guy in the eye, crushed his hand in a handshake, and said, ‘Maybe we’ll do business one day,’ then walked off. I think my obliviousness unsettled him more than fear would’ve.

That kind of blind momentum got me through. If I’d stopped to consider the risks – the location, the crime rate, the reputation – I’d never have gone near it. But I saw a sloping floor and thought, this’d be a great place for gigs. So I went for it. I flew to LA with a home-printed brochure to pitch the Academy. Told agents it was closer to Buckingham Palace than Hammersmith or Wembley – which, on the Tube, is technically true! They didn’t know Brixton’s reputation, so I convinced the Red Hot Chili Peppers to play there. UK agents were livid – they’d told me I’d never get a rock band.

But I wasn’t following the rules – and the Americans loved that. They said I was the only venue operator who’d ever flown out to meet them. That’s how I got in with the big agencies – CAA, William Morris, the lot. If I’d done what I was supposed to, none of it would’ve happened.

You’ve talked a lot about gut instinct and doing what excites you. Do you think that impulsiveness has always been part of your makeup?

Definitely. My concentration’s awful – always has been. Give me a long contract, and I can’t get through it. I’ve got a decent legal brain, but I can’t hold focus on dense paperwork. I’m not someone who sits still easily.

When I was at school, they just thought I was thick. Dyslexia wasn’t recognised then – you were just bad at English. They took me out of French because they said I struggled enough with my own language. But I was good at maths and art. I’ve always had that kind of brain – creative, numbers-focused, but not into the academic stuff.

And yeah, I’m impulsive. I don’t mean reckless – just instinctive. I’ve always followed my gut. If something doesn’t feel right, I walk away. When I’ve ignored that instinct, it’s cost me. And when I’ve followed it, even when it didn’t make sense on paper, it’s usually worked out. People talk themselves out of things. They overanalyse, get spooked by risk. But sometimes, you’ve just got to back yourself and go for it.

That’s how I ran the Academy. No grand business plan. Just belief, momentum, and a bit of madness. I lost everything at one point – house, money, the lot – but I got back on my feet. I don’t regret a thing. If I’d done it all by the book, maybe I’d be richer, but I wouldn’t have had half as much fun.

You’ve built an incredible legacy – and I can’t wait to see it come to life on stage.

Brixton Calling is at the Southwark Playhouse – Borough from 23rd July to 16th Aug. Tickets from southwarkplayhouse.co.uk

Words by Nick Barr

Colour Photography by Leo Fawkes

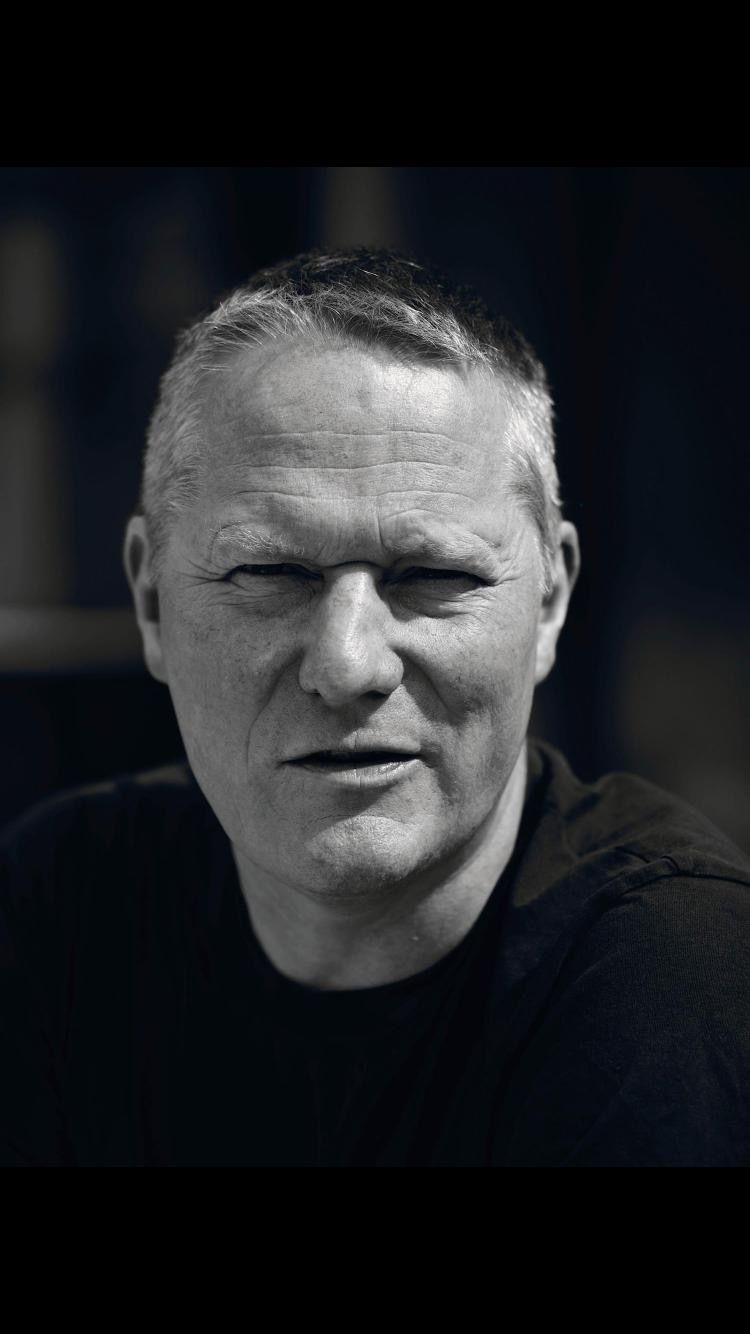

B&W Portrait by Andrew Coulbeck