The Land of The Living, newly opened at the Dorfman Theatre, centres on displaced children during the Second World War, and the desperate quest to locate them and return them to their families. This is not the nostalgic world of The Railway Children or Narnia that we are accustomed to, but rather a far darker story of children taken from their parents to be measured against Nazi standards, in order to determine if they might form part of the ‘Aryan race’.

The set, designed by Miriam Buether, is strikingly beautiful. A long catwalk-style thrust stage dominates the space, with a door, bookcase, and piano at one end, and a kitchen and further doorway at the other. This simple yet clever design elevates the entire performance. By placing much of the action on the central catwalk, the production avoids the need for elaborate backdrop changes, allowing the story to flow more seamlessly. It transports the audience with ease and keeps the focus firmly on the performers.

The acting, overall, is of the high standards one expects from the National Theatre. The cast give it their all, and there is a sense of commitment and energy throughout. Many of the performers deliver lines in multiple languages. While I cannot vouch for the absolute accuracy, the delivery sounded convincing from a British perspective and lent the piece a layer of authenticity.

Young Thomas, played by Artie Wilkinson-Hunt, deserves particular mention. Primarily performing in languages other than his own, he never falters and brings a fresh, compelling quality to the production. He is a clear asset to the company.

That said, audiences should be aware of several intense moments. There is frequent shouting, the crashing of plates, a chair smashed on stage, and even the firing of a blank gunshot. While these moments are intended to capture the volatility of a traumatised child lashing out, the repetition dulled their impact for me. A particularly effective moment comes when Young Thomas runs behind the audience, shouting and smashing objects in the corridors, but beyond this it became a little too much, losing some of the intended power.

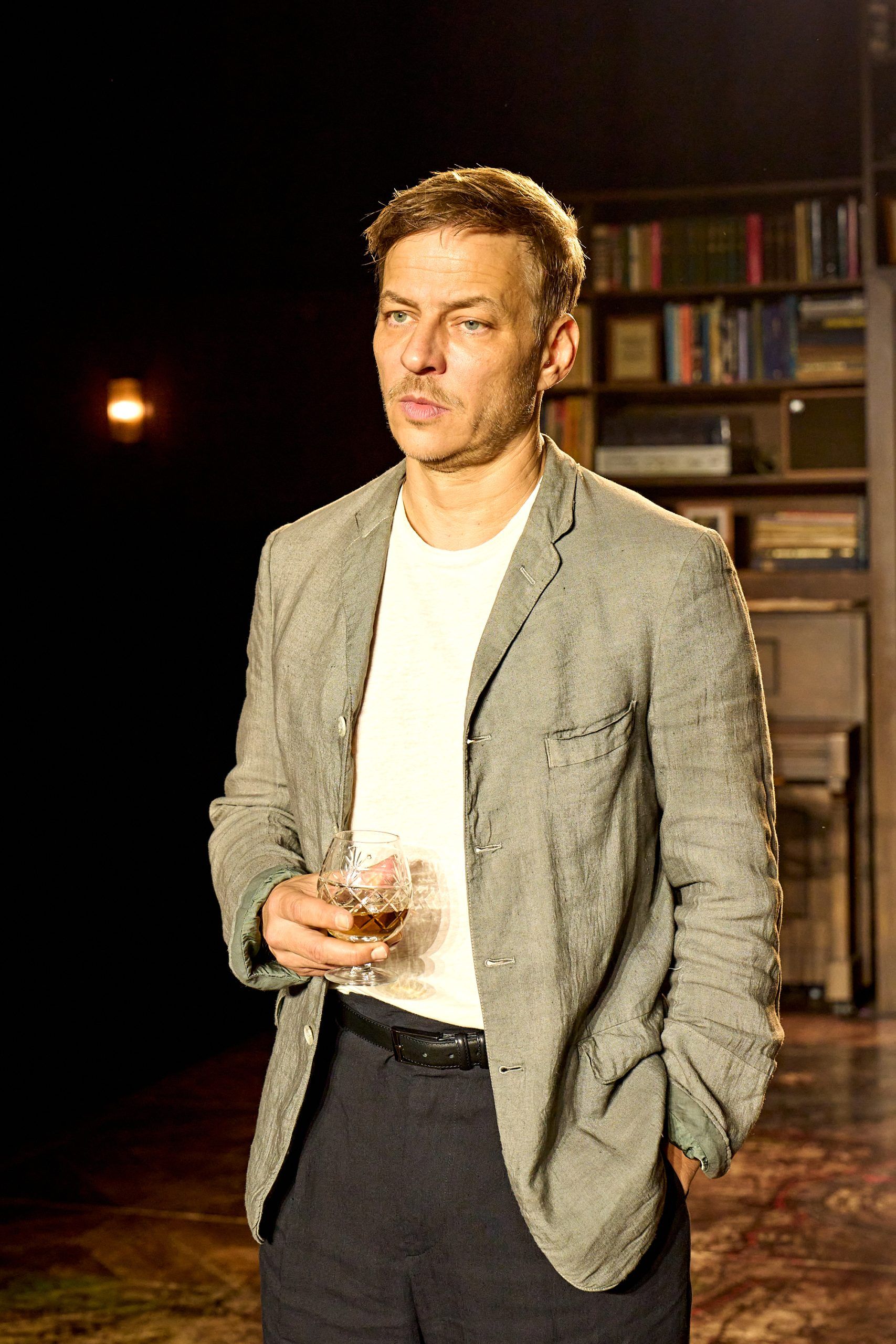

The narrative structure is unusual, and at times confusing. We begin with the adult Thomas (Tom Wlaschiha) meeting Ruth (Juliet Stevenson), before sliding into a semi-flashback in which Thomas observes events as Ruth narrates and participates. Many audience members remarked during the interval that they struggled to follow this device. Young Thomas is played by a child actor, but Ruth is performed in both timelines by Stevenson, which made it harder to distinguish past from present. At one point, Ruth remarks, “I was only 20,” which completely shifted my understanding of her role. Until then, I had assumed she was much older in the flashbacks, a commanding force amongst the younger ones, rather than their peer. Reading the programme notes, I learned the time gap between past and present was 45 years, something I wish had been clearer on stage. Casting a younger actress as ‘Young Ruth’ in the flashbacks, as was done with Thomas, might have solved this issue and added a new layer to the play.

There are also jarring moments where characters interact with the older Thomas within the flashback, patting him on the back, for example. This breaks the illusion of his ghost-like observation, reminiscent of A Christmas Carol. As a result, the production sometimes felt caught between styles without fully committing to one.

The decision to reveal both leads alive and well in the opening scene also reduces dramatic tension. In a wartime drama, jeopardy is everything, and knowing their survival from the outset undercuts the stakes. A memoir-style narration or interview format might have achieved the same reflective tone without diminishing suspense if flashback is important.

Some plot points are similarly underdeveloped. Ruth’s cough and bouts of cramp recur throughout, and other characters comment on her eating habits, but no explanation is ever offered. It resurfaces in her older self, but with no payoff – it feels like a missed thread or a forgotten plot.

The briefcase sequence is another confusing moment. A woman hands over the case in tears, insisting it be taken quickly before she changes her mind. The mystery builds, but when it is opened later to reveal a dress symbolising a little girl, puppeted briefly, it feels disconnected. All other children, except Young Thomas, are mimed rather than represented through objects, making this choice inconsistent and puzzling.

Given its subject matter, one would expect the play to be profoundly moving. Displaced children, wartime horrors, and the search for identity should make for a deeply emotional piece. Yet, despite strong performances and impressive staging, The Land of The Living somehow feels strangely detached from its own emotional core. It is only in the closing moments, with a hauntingly beautiful piano solo, that the play truly touches the heart.

The Land of The Living is playing at the Dorfman at The National Theatre until 1st November 2025.

Book your tickets at nationaltheatre.org.uk

Words by Valentine Gale-Sides

Photography by Manuel Harlan