Indie rock isn’t a new genre by any means – but in the late aughts and early 2010s indie rock was developing a new sound. The music was fun and a little bit poppy; it still had some of the grit and grunge of the rock that preceded it, but this was something new. This was an era of music that would come to redefine the genre. Think songs like Tongue Tied by Grouplove, Take a Walk by Passion Pit, My Type by Saint Motel. If you’re going to make a list of genre-defining tracks you have to also include Young the Giant. Apartment, Cough Syrup, My Body – any of these songs should be considered when compiling a list of the best, early days of indie rock.

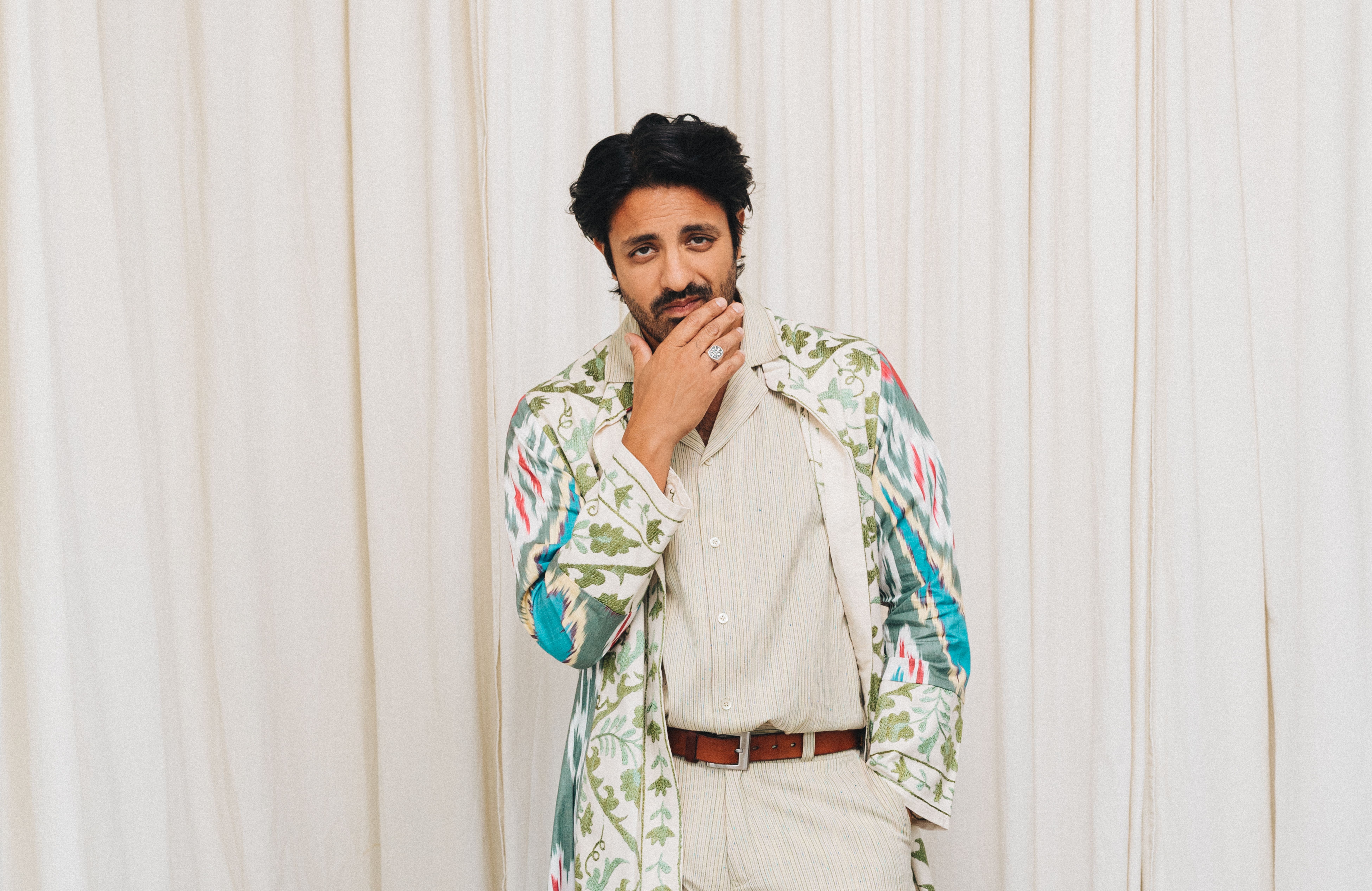

Of course, time passes. And with it so too passes the trends of music. Indie rock’s sound has grown and changed and yet again, Young the Giant is helping to define this era. On their new record, American Bollywood, the band tells lead singer Sameer Gadhia’s family’s immigration story and then traces Sameer’s personal struggle to define his own cultural identity as a South Asian American in Southern California.

The record is separated into four distinct acts – I. Origins, II. Exile, III. Battle, IV. Denouement – each one incorporating Indian instrumentation into their more traditional indie rock sound. This album marks a change in Young the Giant’s catalog, and the genre as a whole. Indie rock isn’t quite as white washed anymore – it’s embracing new people and sounds. And Young the Giant is here to help champion this new wave.

In conversation with 1883 Magazine, Sameer Gadhia discusses what it’s like incorporating Indian instruments into the music he and the band creates, what “mystical punk” is, and what it feels like to share his family’s story with the world.

Before we get started, my mom has requested that I tell you she’s a really big fan.

[Laughs] That’s amazing.

That’s one of our favourite memories actually, I brought her to a Young the Giant concert a few years ago and she was blown away. You’re a really big deal in my house. I‘m thrilled to be talking to you today. I listened to the new record. I think it’s phenomenal. And I’m really excited to talk about it with you. My first question has to do with the way this record was released. It was released in parts. I read that one of your inspirations while working on the album was the Amar Chitra Katha comic books. Releasing the record in this way reminded me of the serialized format of comic book releases. Was that intentionally done?

Yeah. That was a big part of it. We wanted to bring that sense of anticipation and waiting. It was also the best pathway for me to get into the narrative. That was really cool and exciting and made it feel like it was my own in some way. And also allowed me to appreciate each part of it. So that most definitely weighed into it. It’s also been four years since we’ve released anything and we wanted this record to really be massively wide in scope. It’s a 16 song record. We could have put a lot more songs on it but we settled at 16 and we wanted people to be able to live with each set of four as opposed to just kind of trying to binge through it all.

It definitely forces you to listen really closely to what’s been released. If you only have a short little tidbit, you’re on the edge of your seat like, “Oh, I gotta keep listening.” It forces you to pay really close attention and not get overwhelmed by the rest of the tracks. Sonically the album on the whole incorporates a lot of Indian instruments into the pieces, sitar and tablas among others. Had you used those instruments before writing and recording this album?

Not as much within Young the Giant. The tambura is something that the band’s used since the third record. I’ve used that machine as a songwriter since I was a teenager because it was just in the house. I would take the tambura with me to gigs sometimes and start jamming to it because it’s really beautiful and pleasant sounding. And it just has been a part of that. The rest of the instruments that are obviously integral to my history of musical understanding. My dad was a tabla player. I have my grandma’s harmonium and I would play on that. And so there are these elements, but I’m not classically trained in any of them.

One of the big ethoses for this record was this almost punk approach to the music and the use of Indian instruments and instrumentation. I wanted to bring intuition and the gut of what I would instinctively try to do with these instruments as someone who’s more steeped in Western music – what would I do with Eastern instruments? And that was kind of the point, you know. American Bollywood in general is telling the story of someone caught in between two places and so it was intentional that that was the case with the instrumentation. Same with the dhol drum, which is a Punjabi drum that I had been obsessed with using for a very long time because it utilizes a triplet feel that we use a lot in modern music these days, you know, like trap music and in pretty much every rap song the cadence is a triplet over four beats. So, that’s something that I wanted to incorporate.

The first act is very conscious and then the second, third and fourth acts reflect the influence of South Asian instrumentation, and songwriting, and the lyrical matter becomes a little bit more subtle. I think I was trying to show how deeply rooted the influences are in places that we might not even expect. People might hear a song like The Walk Home, and think that they don’t really hear any Indian parts in it. But there are still many in terms of the way that the vocal shifts and changes and in the notes that I’m singing, etc.

What was it like incorporating those instruments into your repertoire? As you’ve mentioned you’ve been very steeped in a traditional Western indie rock sound. What was it like adding this new flair to everything?

You know, it somehow felt really natural. I think as a band, we’ve always tried to break tradition and I think that “Young the Giant sound,” for better or for worse, is that we don’t really have a sound. We love to explore and live on the edges of multiple places and I think in some ways, some people think of that as a weakness because some people think of music as a brand and that you should sound like a brand and that’s not who we are. We believe in evolution and change and the humanity of being able to be a multifaceted thing. So when we wanted to incorporate stuff like this, the real challenge was not accepting that that was what we wanted to use, but that we wanted to bring it in with respect and subtlety and not have it feel like it was fusion world music. That’s a really fine balance. So that was what we were mostly preoccupied with.

How did you navigate finding that balance? Because that sounds like it would be really hard.

I think we just kind of leaned on our taste and what we like and you know, taste is subjective. For example, I hate guitar solos.

Hot take!

I don’t like guitar solos for the most part, unless they’re really intentional… And I think whenever there is a guitar solo, within Young the Giant stuff, it’s intentional, but that comes from my own subjectivity of taste, and what I like to listen to. It could potentially be a hot take. But, for example, when we’re doing sitar when we’re doing drums, it’s like, nothing there is meant to distract you from the overall message and the overall feeling as long as it adds to the feeling, then that’s important. But if it’s trying to distract you and take you away and say, “Look how shiny and awesome I am,” then it’s doing a disservice. So it’s just like a continuous gut check of that.

Obviously, the record on the whole is about your family’s immigration story and how it has shaped and changed both you as a person and your family too. What do you think this album will mean to your family and other immigrants to America?

I think it’s exciting. It’s still early days, but my family is just so honored to have been a part of this. I’m so honored to tell their story. I think regardless of whether you’re a first generation, fifth generation, tenth generation immigrant from anywhere in the world, there’s always been a fascination for me of what our origin story is. What led us to this place? If you go back enough generations, you’ll find some really beautiful, interesting stories, and the landing place of our comfortability and our privilege comes from these really crazy stories. That’s what I wanted to pay homage to and I think people appreciate that. There’s a really cliche idea of, okay, immigration is about sacrifice and struggle. And that’s, most definitely an element of it, but it’s also about the strength of love, really, and how what we do for love is amazing as humans and I think that that is a very universal concept.

Even though this story is uniquely personal, and is true to you, it’s also something that can be understood and felt by everyone. My family is a family of immigrants also, but it’s been a different experience for me being a white person, especially in Canada. And yet there are still elements that are super relatable. I think that that’s a really important sentiment, especially in this time period, where people are able to put themselves in one another’s shoes.

I think the takeaways of this record follow the arc of The Mahabharata mythology and the immigrant story, but it’s also about us right now. The Mahabharata mythology is based on these five brothers who are heirs to the throne, and they’re exiled from their own kingdom over a rigged game of dice and banished to the forest for 12 years. Finally, one year they return and live in anonymity, and then there’s this battle to reclaim their right to the throne. They win the battle and that would be where the story ends in a lot of mythology – it’s the natural ending point. But there’s a whole subsequent act and in that act the brothers become disillusioned with power, and the infinite. If there’s humanity there’s goodness, but there will always be evil as well. And everyone manifests those things together. There’s no binary between good and evil. We love to tell those stories – in our world and especially in our politics – we love the idea of good versus evil. And I think it’s just so much more gray than that.

Yeah, there’s so much more nuance to it. I think people shy away from the concept of gray areas because it’s a lot more complicated. It’s harder to explain the gray when black and white is so much easier to distill. But it’s incorrect. Or not incorrect so much as it misses the dimensions of everything else.

Yeah, totally.

How long have you been wanting to record on the subject matter?

In some ways, I think it’s always been there and maybe this is just the most on my sleeve I’ve been about it. In Mirror Master, we were starting to talk about these concepts and even in the song Superposition – it’s about this unification of these two completely different ideas. That desire of trying to find a place that is all in the gray area has been my whole life – I’ve never really thought of anything as black or white. For me there’s always something in between, you know, and I think maybe it’s just always been there, but this time, it’s the biggest part of the album.

You’ve been quoted calling this record “mystical punk”. I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit more about the influences that inspired you to delve into this new sub genre?

Yeah, yeah. I mean, we kind of touched upon a bit of the punk aspects. I don’t think anyone would call Young the Giant a punk band. We love to curate, we love to create things with a higher architecture and that in some ways goes against the ethos of what punk is, but in terms of the way we approach our instruments and the way that we approach our songwriting – we go with what makes us feel something.

I think the thing that unites both this mysticism, and this punk approach, especially with the Indian instruments, is that we were coming at this like, “Okay, we don’t know how to play these instruments at all. But luckily we have them here. So let’s figure out what we can do that sounds good to us.” So that was the punk aspect. And I think the mysticism is about reclaiming that mystic narrative. There’s so much in modern, Western culture that showcases Eastern medicine stuff and spirituality. And I think all that’s beautiful. I think that’s all important, but I wanted repoint the arrow to show people that this is where it came from, to try to reclaim that. A lot of the lyrical matter is really mystical. It’s kind of like bringing everyday spirituality in – some of the songs are a lot more straight and narrow in terms of what we’re talking about. But that sense of mysticism mostly lives in the lyrical content.

Yeah, definitely. I noticed that. Another thing that I noticed lyrically is you’re talking about love and being a dad. This is your first album to come out since you had your son. In I Bite you’re talking about unconditional love and being a good example to your son and just fatherhood in general. That song even sounds like it starts off like it’s a lullaby. How do you think fatherhood and marriage has influenced the kind of music that you create now?

I think fatherhood is a big part of maybe the reason why I wanted to even tell this story. I was thinking, what do I pass on? Like, if I know my parents’ stories now and I know my grandparents’ stories, what is my story that I pass on to my children? And what do I want to say? What’s important for them to know?

My kids are multiracial children. And a part of that is obviously fusing two different cultures and some of that gets lost in translation. That was a big part of this. I think when you have kids in general, you have to really think about who you are and try to stop some of this generational trauma that you’ve carried and learn from those experiences. I think personal growth is something that’s very inspiring for music as well.

Another theme that I noticed as well throughout the record, is this idea that we’re all still the same people even though we’re different from one another. That most obviously comes out on Otherside and Same folk, but even in Wake Up you’re talking about the Indus River Valley, which is the cradle of civilization. I’m an archaeology minor so that was exciting for me to hear haha. It brings to mind for me that quote, “We’re all from Africa.” The experiences that you share on the album are uniquely yours, but they can be felt universally. Was it your intention when you were writing, or is this more of a happy byproduct?

I mean, I think it is an intention. I think we are united in what we don’t know. That’s a big part of my upbringing and in Hinduism in general, the idea of embracing chaos and this illusion of truth in the things that we believe in.

It’s a dangerous rhetoric because I think that saying that we’re all the same and that we should just get along has obviously been politicized. I don’t want to discount hundreds and thousands of years of cultural molding. We have become, in some so many ways, different. A lot of neurologists would say that our brains all work in massively different ways. And that is true. But I am still obviously excited by this concept of coming from the same place and coming from a place that we all have walked many thousands of years away from. But there was a place where we were all in the same moment. Like any multi generational story, you can talk about where any story begins. And if you were to go back, obviously, to the very beginning, it would be to one of those early groups of people.

Yeah, it’s important again, to bring back that nuance. We are all the same, but our experiences are not. I think that comes across in the record as well, especially with the influence of the ancient Indian instruments. It’s nuanced, not so heavy handed. It’s just a little sprinkling in. I loved it. And I think, as someone who listens to tons of Western indie rock music, it’s really refreshing and exciting to listen to something that’s a little bit different, too.

Thank you.

In doing my research for this interview, I came across another interview you’d done with Billboard in May of 2021. You were discussing the American dream and assimilation and how you’re excited to see the tides of indie music changing. I think that this record really represents that change. How does it feel to see it all come together cohesively and to be able to share it with the world now?

It feels exciting. It feels overwhelming. You know, this is just the beginning of it. I think, in general, like we all talked about, people want to have things be black and white. And when you try to show people nuance, it just takes a little bit longer. This is something that will be a marathon, we’ll just kind of see where things go. I’m interested in how this affects the landscape of the genre, and I’m very hopeful for it. So far, it’s been really really cool to see among our fans. We’ve had a handful of shows so far and we can see that people are really resonating with this. I think it’s one of the beginnings of a new era for this genre and I’m very excited for it.

Interview Kendall Saretsky

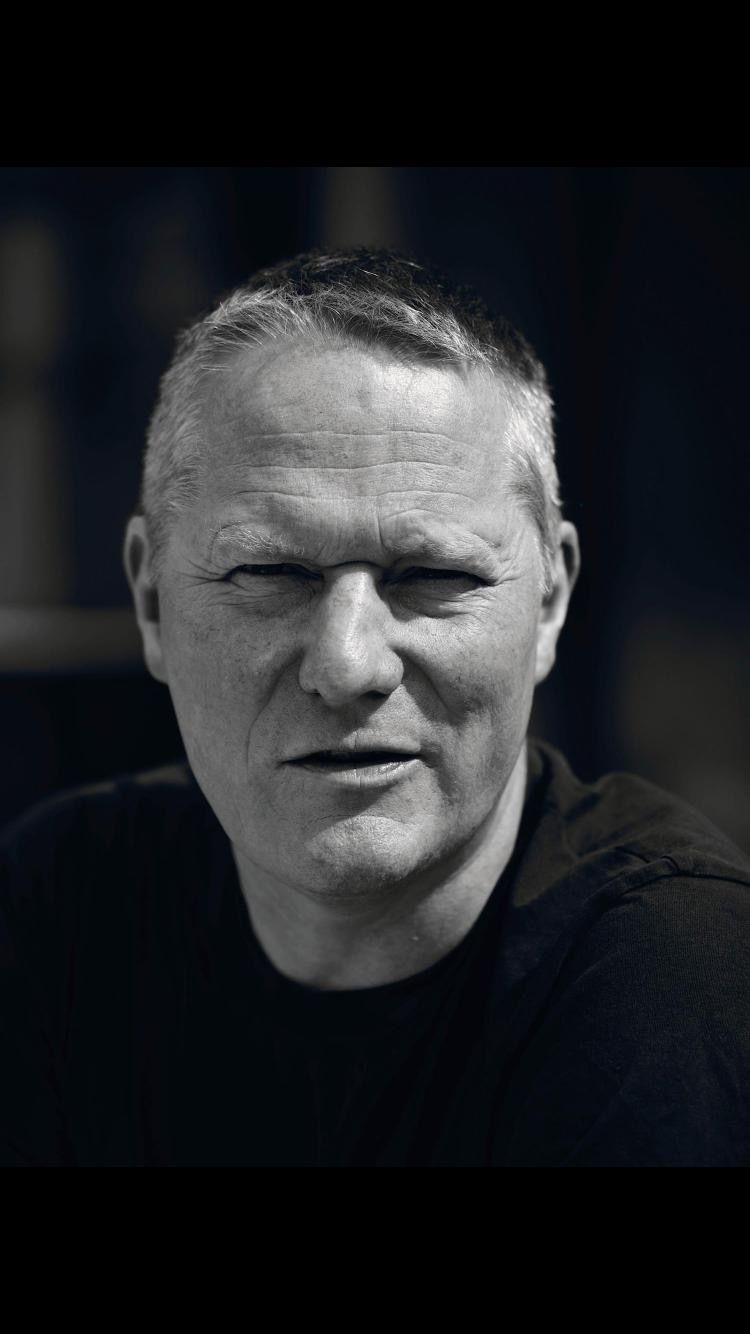

Photography M.K. Sadler and Natasha-Wilson