Brett Morgen

Brett Morgen’s ethereal odyssey of David Bowie’s life isn’t his first love letter to a musician.

Morgen began making documentaries whilst studying for his MFA at New York University in the 1980s, going on to release his first feature On The Ropes. The film studied three aspiring boxers and won Morgen the Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Documentary by the Directors Guild of America. Brett then went on to make The Kid Stays in the Picture, a biopic about the film producer Robert Evans (The Godfather, Rosemary’s Baby). His first music documentary Crossfire Hurricane in 2012 and really introduced the world to Brett’s distinct storytelling methods. Arguably Morgen’s biggest picture to date, the award-winning Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck focused on the life of Nirvana’s lead singer Kurt Cobain through personal archives, using music and sound collages to explore his life.

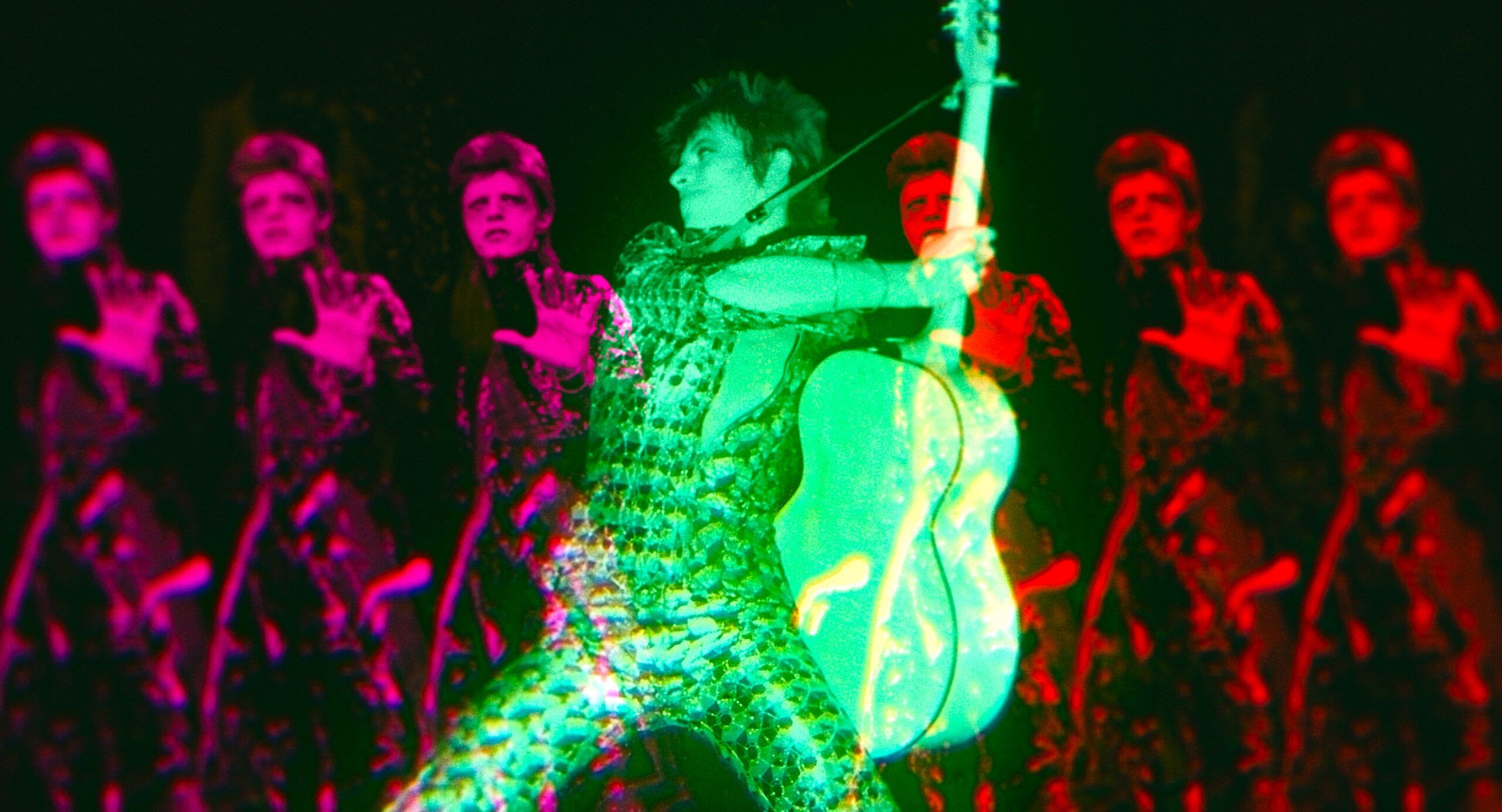

Brett returns to musical documentary for his new feature Moonage Daydream, a film that he refers to in our interview as the “light” that contrasts the darkness of Montage of Heck. These films in no way glamourise their chosen subjects, but instead guide you through their stories in a more visceral approach, offering fragments of what one may feel in such a position of musical success. Brett’s admiration for both artists is depicted so differently, homing into completely different aesthetics whilst simultaneously still holding their talent to the highest regard. The artistic style choice embraces his individuality, painting him on a canvas rather than telling a linear story. A true visual masterpiece, Moonage Daydream is sure to win over the hearts of new listeners and Bowie fans alike. 1883 Magazine spoke with Brett about the release of Moonage Daydream, rejecting perfection, and the trick to meeting your heroes.

Moonage Daydream – in cinemas this week.

So, I saw you dancing at Cannes on YouTube – iconic. I want to know when your love for Bowie really began?

Thank you! David came into my life at the point that I was entering puberty – actually, I don’t know what came first, puberty or Bowie. They both served this very similar function, in taking me from adolescence into my adult years. I came of age in the early 80s, and I think for several generations beginning in the early 70s through to today, many of us come to Bowie around the same time. He was one of the first artists who I had purchased his music myself, as opposed to borrowing my parents’ records. So, through Bowie I began to curate my own kind of culture and my own view of the world. At that age where you start to question your identity, and some of the deeper questions about who we are and why we feel different – there’s David Bowie to tell you to raise your freak flag. Similar in a way that I think Kurt Cobain made a lot of people in my generation feel that they weren’t alone. In the days before the internet, it was impossible to express how enormous that was. I mean, if you were a gay kid growing up before the internet, there was David Bowie… and there weren’t a lot of other people who were publicly coming out at that point. When David did it, it could have been career suicide. Russell Hardy who David is speaking with about it in the film was gay. That’s the craziest thing. The courage for David to take the stance he did, which he did repeatedly throughout his is life and career.

I think one of the biggest takeaways from me about Bowie is his courage, and the audacity to risk everything. Time and time again, to risk your fame, to risk your audience. To say that the most important thing is that “I’m satisfying my creative desires, and if the audience wants to come along, that’s great”. There weren’t a lot of people who were in the mainstream, or who had that sort of financial success that were willing to risk it all. The reason he took risks was quite simple. He understood that there was a limited time on this earth. So, once you’ve mastered something, why continue doing it? What else is there? When you feel that you are at the top of your game, say as a journalist, and you’re just repeating and falling back on your instincts, it’s time to get out!

Why the decision not to make a biopic, and opt for something more Avant Garde?

There’s been dozens of books on Bowie, and dozens of documentaries. If you want to know what Tony Defries thinks, or Tony Visconti, or who Angie is, or any of the characters in his life, you can read a 500-page book about it. There’s no more space for me in that world, and I wondered what I can offer that none of these other pieces of media have offered me. To me, it was the experience. It made so much sense because trying to understand or deconstruct David Bowie is a fool’s error. And why would one want to? What’s great about Bowie is the mystery, the enigma. To not tear that apart, but to actually embrace it and create a film experience that mirrored the experience of listening to a Bowie song, so that it’s mysterious and enigmatic! There are references that you may or may not know, and it doesn’t really matter whether you know them.The thing about Bowie is, as he says, he is a canvas. But while we can say that all artists are canvases, Bowie was very conscious of not being so literal and overt in his art that it doesn’t leave room for interpretation. His work is designed to invite us to project. The more we listen to David Bowie, the more we learn about ourselves.

How did the idea for Moonage Daydream come about?

I had this idea to do this immersive music project and I was reaching out to several artists. I did a movie called Montage of Heck about Kurt Cobain which is, in many ways, the ultimate cradle-to-the-grave biography. It’s not a traditional one, I don’t think, but nonetheless, it’s very Kurt. It’s actually a good comparison to Bowie because the Cobain film is really about pain, and about how every moment for Kurt was fraught with hurt; and with Bowie, it’s the opposite – every moment was an opportunity. It was very different experience. When I finished Montage and because Kurt had such a short life, it was easy to go cradle to the grave and feel sort of completus about it, but I didn’t think there was anything more for me in the biographical space. I realised that the thing that I liked most about these movies is the texture and the ambiance. I just wanted to sort of strip away the facts and create something more musical.

You would have spent so long looking at footage to put this film together – do you feel like consuming so much of his personality has influenced change in yourself from when the process began?

Yes, majorly. I had a massive heart attack and I flatlined at the very beginning of the film, probably about four months before I started going through all the archives. When I came out of my coma, I was the same person I was before I had a heart attack – it’s not like that stopped me. The first words out of my mouth to my surgeon were “I’m directing a very important pilot for Marvel. I need to be on set on Monday!” and he goes “You’re not going to be anywhere; you’re going to be here on Monday”. I said to him “No, you don’t understand. It’s Runaways. I need to be there”. That’s how fucked up I was.

I think from that moment, I started to ingest Bowie. He changed my life. He altered the direction of my life when I was a teenager, but as a 47-year-old, he provided me with a roadmap to how to lead a more balanced and satisfying life in an age of chaos and fragmentation. I have three kids, who are 19, 17 and 14. I almost flatlined when they were young, seven years ago. I’m not anywhere near as wise as David, but I kept asking myself ‘What is the thing my kids are gonna say, when and if I die, like dad used to always say’. I didn’t know what it was, and I realised I had an opportunity through David to present them with a map of vision on how to do it right. I don’t think there are many people who walked this earth who’ve done it as gracefully and successfully as David Bowie.

Moonage Daydream – in cinemas this week.

There’s also a lot of pressure to make a film about someone that is no longer here – how did you deal with that whilst in production?

I would have felt way more pressure if he was alive to see it. I think a lot of people have asked me about the weight of taking on a legend that means so much to so many people. And that’s why I spent seven years; you know. It was not a job for hire, it wasn’t about a paycheck. I didn’t get paid for the last five years I was on the film. I paid to go to work every day is ultimately what happened. So, there’s certainly a determination and a drive to leave no stone unturned. But at the end of the day, I walked to my mirror feeling like I did the best I could do. Yeah. I do have a certain degree of confidence, having seen more than any person who wants to debate or argue or discuss this or that. I feel pretty comfortable with the decisions I made. Like I had a fairly good vantage point. If you’re intimidated by the legend, you probably shouldn’t be doing a project… it’s probably not the right thing for you. Put it this way, if you want to connect with some icon that you admire and worship, but when someone introduces you, you start quivering in the room – you’re not going to connect with them. So, it’s important to try to find the familiar, and the relatable, and see them eye to eye.

I think ultimately, I can’t divorce myself from my own history and context. When I’m looking, let’s say at the Cobain archives, the stuff that I’m just intuitively drawn to obviously is going to be different than the stuff you’re drawn to. In the case of Cobain, I felt like I was making a film about my family, my mother, my insecurities, and my sense of shame that I’ve had with me my whole life. So, I don’t know if someone else would have gone there but it was crystallized for me, what hurts; I related immensely.

I’m an intellectual midget next to David Bowie, that really was the hardest part because I pride myself on being a method director and absorbing all of the cultures that my subjects absorbed. Eating the foods that they eat, wearing the clothes, I really try to go all in. The thing about method acting is that if you do it right, then you can go and act in any environment or situation; you should know how that person is going to act in that situation. As a method director, it’s very much the same thing. You really are trying to get inside the head and the skin of the subjects so that you can try to maintain some continuity, and consistency.

I’m more interested in viewing the world from the inside out, rather than the outside in. I think that’s not very ‘documentary’. I think the word documentary implies you’re documenting, you’re observing. You’re capturing a known moment, right? I’m constructing moments. I’m interested in truth, but I’m not interested in facts. I’m interested in emotional truths. I’m interested in colour and sound and the collision of colour and sound. Images and what happens when you put two images together what is then the meaning, like a Rorschach test. This film was like a creative playground. It was like anything goes.

I was just reading someone commented that they thought the film was a little indulgent. I have to say I was offended. I was like a little indulgent! I am not into minimalist art, right? As an artist, I’m not really into restraining myself. Sometimes I’ve done that; I made a movie Jane Goodall and I tried to soften some of my instincts. But I think that art is indulgent. I don’t think indulgence is to be a bad word when we’re talking about art. David totally embraced the idea of freedom. When someone tried to say he’s pretentious, like in criticism, why? It’s something that scares people. It’s sort of being intellectually audacious, right? Okay, yeah… why is that so offensive? I don’t know. I think that perhaps we get scared of these labels, so we don’t do certain things because it’s going to be called pretentious or whatever. I made a film about the meaning of life. How fucking pretentious is that?!

You know, I saw the George Miller film that just came out – 3000 Years of Longing – the saddest state of film criticism is that that film is like 60% on Rotten Tomatoes. There are some problems with the film, the scripts not perfect, whatever. But that is a film where this artist is asking questions that are so enormous that it’s easy to dismiss as pretentious or indulgent. Everyone should go see 3000 Years of Longing – it’s one of the most exhilarating cinematic experiences of the year. I’m going off subject.

I’ll definitely check it out! Just returning to the visuals of the film that you spoke about. Finally, I wanted to know what your creative intentions were for the artistic style – if you had a clear vision from the beginning, or this was something that happened as the process developed?

I went into the film with a very strong idea of what I wanted it to sound and look like. I knew that obviously, it wasn’t gonna be biographical, I think that my vision for the film was probably more in sync with what the first eight or nine minutes of the film ended up being.

At some point, I needed to endorse more narrative and a few more biographical components in order to flesh out the story. That gave me an existential crisis because I had set up this set of rules for myself that there’s no biographies, there’s no dates, there’s no information. We can just project everything onto David. But because he talks so much about alienation and isolation, I just felt the audience as well as myself 30 minutes in are going to be like “Where’s this coming from?” and so I had to then introduce some biographical components. I felt that the second you open that door, you open yourself to criticism. If you mentioned Iman, why didn’t you mention Angie? Or if you mentioned Brian, why don’t you mention Tony? I knew I was opening the door to a world of criticism and that I was no longer going to have a perfect film. Art is imperfect! Why am I fucking laying awake at night stressing out that I’m breaking a fucking rule that I created for myself? That was a real game changer, not just for this film, but for probably everything I did. Because up to this point, I invested all my time and energy trying to achieve something that’s not achievable. You know, perfection, you can’t do it. So you get as close to the edge as you can. Again, this goes back to Bowie! Being a virtuoso and rejecting virtuosity. Embracing your mistakes. That was quite a liberating place to be.

MOONAGE DAYDREAM is exclusively in IMAX theatres right now and its UK wide release is from this Friday. Follow Brett Morgen @brettmorgen

Interview by Lucy Crook