Walking into Giant at the Harold Pinter Theatre, I expected a nuanced exploration of an author – Roald Dahl – defending himself against accusations of antisemitism and perhaps earning redemption. I didn’t know the full story. I hadn’t read the article, and I hadn’t researched what he’d said. I went in hoping, perhaps foolishly, that there would be another side to the narrative. What I found was something far more challenging – and far more affecting.

The play, written by Mark Rosenblatt and directed by Nicholas Hytner, takes place over a single day in the summer of 1983, inside Roald Dahl’s Buckinghamshire home. His house is being renovated, quite literally coming apart around him, just as his reputation begins to do the same. He’s just written a piece for The Literary Review criticising Israel’s actions in Lebanon. But his criticisms spiral into something darker: sweeping, antisemitic generalisations that are impossible to ignore.

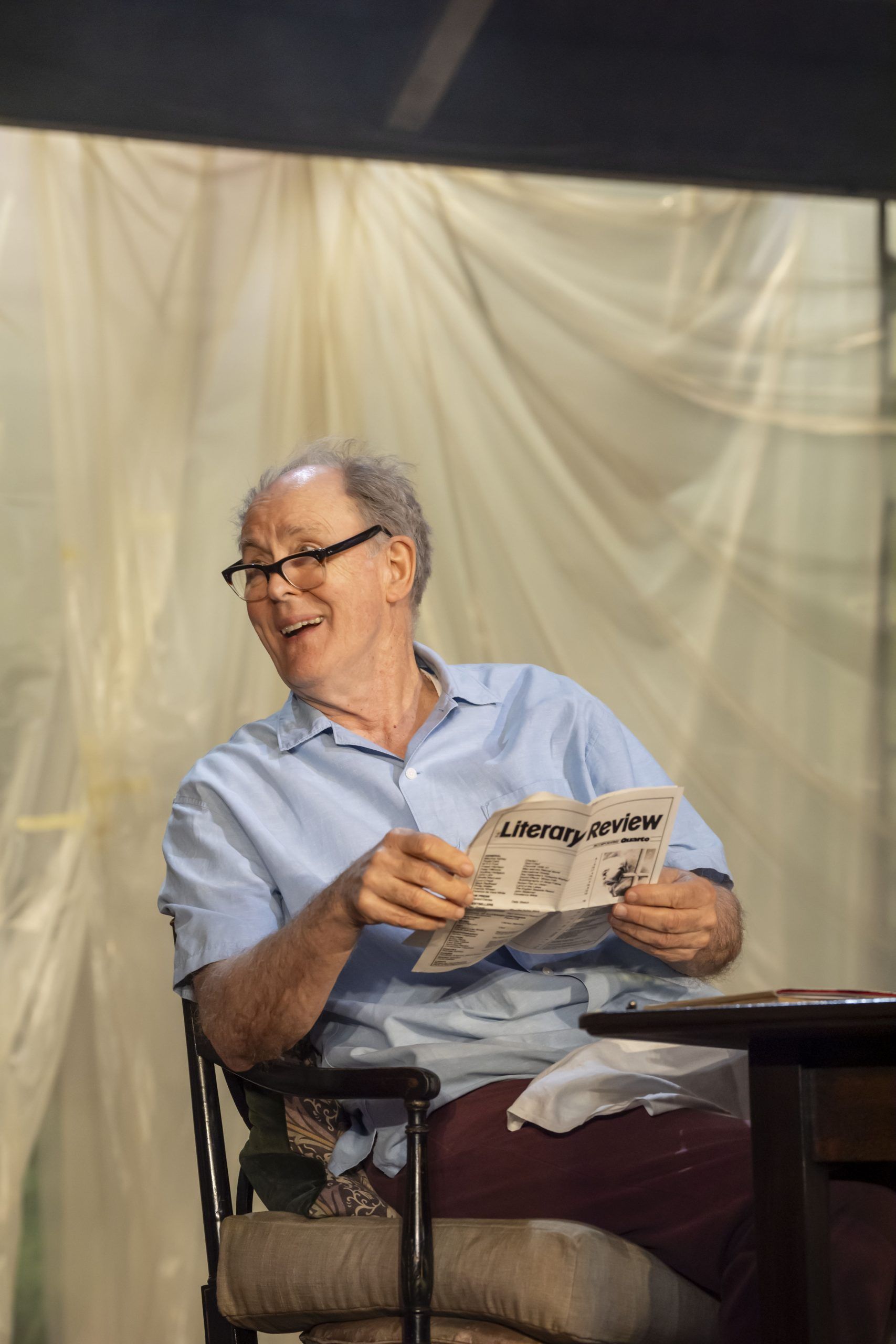

John Lithgow plays Dahl, and his performance is nothing short of masterful. For the first two-thirds of the play, I found myself wondering if maybe, just maybe, he would come around. He’s witty, erudite, and fiercely intelligent. He’s a man in control of a room, even when everyone else in that room is trying to stop him from destroying himself. Lithgow brings a sort of dangerous charm to the part, which makes what follows even harder to watch.

Mrs Jessie Stone, played by Aya Cash, is the Jewish American publishing executive sent by Dahl’s U.S. publisher to urge him – plead with him – to retract or clarify what he wrote. Cash is astonishing. Her performance is full of steel and pain, fury and dignity. She is, in many ways, our stand-in. And watching her get bulldozed, bullied, and then explode with righteous anger is one of the most powerful performances I’ve witnessed on stage this year.

The rest of the cast is equally superb. Elliot Levey, as Tom Maschler, Dahl’s European publisher, brings a quiet, simmering intensity to the role. He’s a Holocaust survivor himself, trying to keep things civil, even as Dahl pushes and provokes. Rachael Stirling is Felicity “Liccy” Crosland, Dahl’s fiancée, who tries – and often fails – to keep him grounded. She walks the impossible line between love and despair, and Stirling makes every beat of it believable.

Tessa Bonham Jones is Hallie, Dahl’s New Zealand housekeeper. A minor role, until one extraordinary moment late in the play when she sits, silent, and watches Dahl with a look of stunned disbelief. In that moment, she becomes us – watching, horrified, unable to look away, a stirring performance that says so much whilst barely moving. Richard Hope rounds out the cast as Wally Saunders, Dahl’s gardener, adding quiet texture to the domestic world unravelling around them.

The set, by Bob Crowley, is brilliant in its simplicity. A half-renovated kitchen, scaffolding visible, walls torn open to the outside, with plastic sheeting giving blurred glimpses of the garden beyond. It’s a house in transition, just like its owner – and just like our image of him.

What hit me hardest, though, wasn’t just the words on stage. It was the mirror it held up to something else. I recognised the wrenching feeling in my stomach, and I couldn’t help but think of J.K. Rowling.

Dahl’s books shaped my childhood, Rowling’s my twenties. Both brought me joy. And then JK used her platform to attack a vulnerable community that I support with all my heart – trans people. The betrayal and sadness I felt watching Giant was the same that I’ve felt watching Rowling double down again and again. Both Dahl and Rowling were/are literary giants. And both chose/choose, to punch down, to use their influence to spread views that hurt people. It’s heartbreaking.

I’m the grandchild of German Jews who fled Berlin before the war. Dahl’s comments in 1983 weren’t theoretical to me. They were personal. I didn’t know the words he’d written before seeing this play. I can now never un-know them. That wasn’t just ‘Jews’ he was talking about, it was me, my dad, our family, our ancestors.

I still love the books. I always will. But Giant has forever changed how I view Roald Dahl and his work. That moment when Lithgow, as Dahl, says “Even a stinker like Hitler didn’t pick on them for no reason” – a direct quote – shocked me to my core. It was like a switch flipped, and suddenly the childhood wonder was sitting in shadow.

And yet, I’m grateful for this play. It doesn’t ask us to cancel. It asks us to confront. It asks us to look directly at someone we admired and see them in full: genius and cruelty, wit and prejudice. It reminds us that accountability matters. That words matter.

I have no doubt that playwright Mark Rosenblatt wrote Giant when he did because Dahl’s views, expressed in that 1983 book review, remain disturbingly resonant today. Dahl blamed all Jewish people for the actions of the Israeli state in Lebanon – and sadly, many today still feel justified in expressing antisemitic rhetoric in response to current events. To hold an entire people accountable for the actions of a government is not just wrong – it’s an absurdity. Life is nuanced. But sadly, far too many people prefer the simplicity of black and white.

What was I left with at the end of the play? A little sadness, certainly a lot to reflect on, but mainly I was moved by the performances I had just witnessed, the brilliant direction, and the honesty of a story that is so timely and relevant and needed to be told. John Lithgow’s Dahl is towering, yes. But not because of his fame or his talent. Because of how far he has to fall.

Giant is a tremendous piece of theatre. Go and see it. Just be ready to feel everything.

Book your tickets at gianttheplay.com before the run ends August 2nd, 2025.

Words by Nick Barr

Photos by Johan Persson