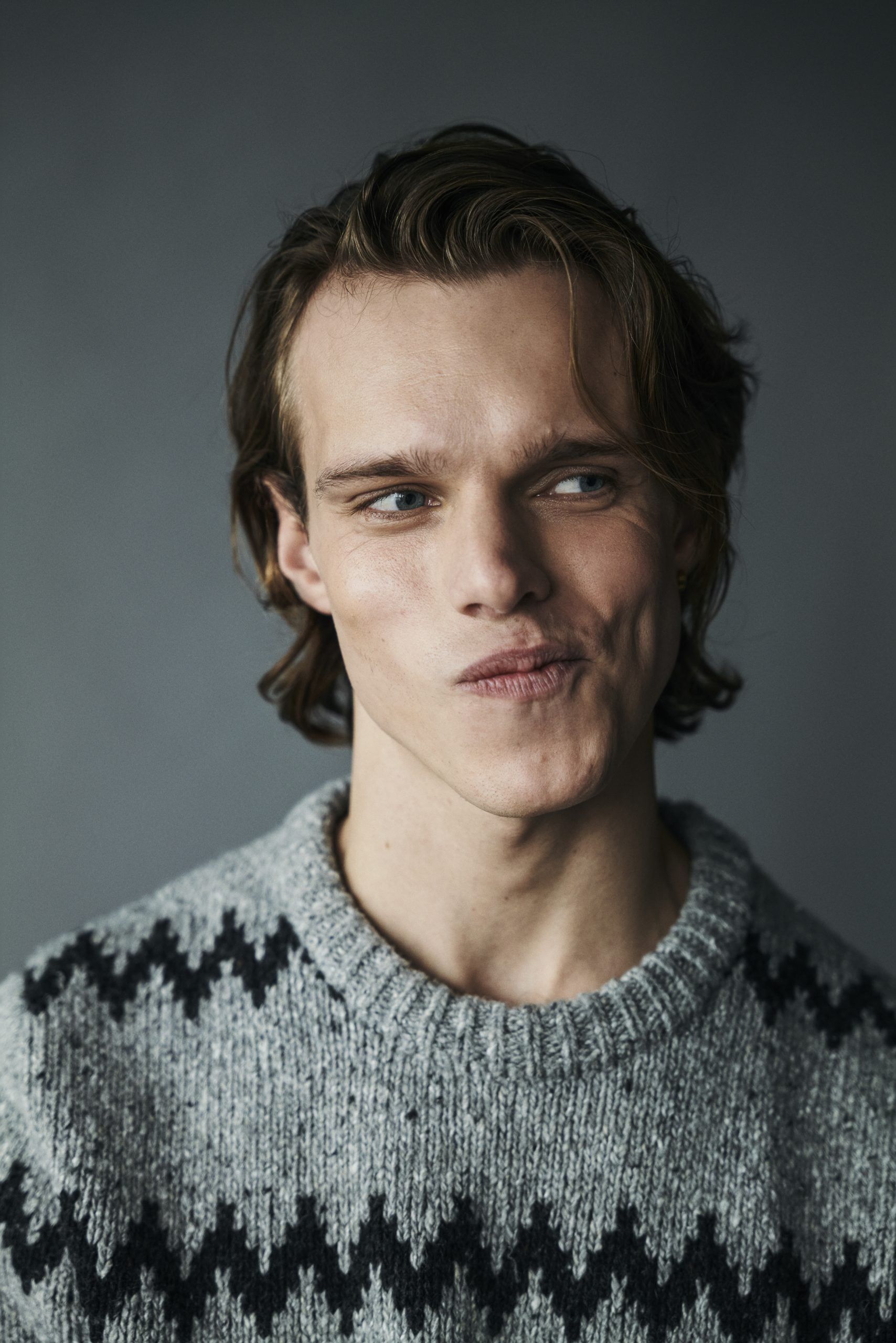

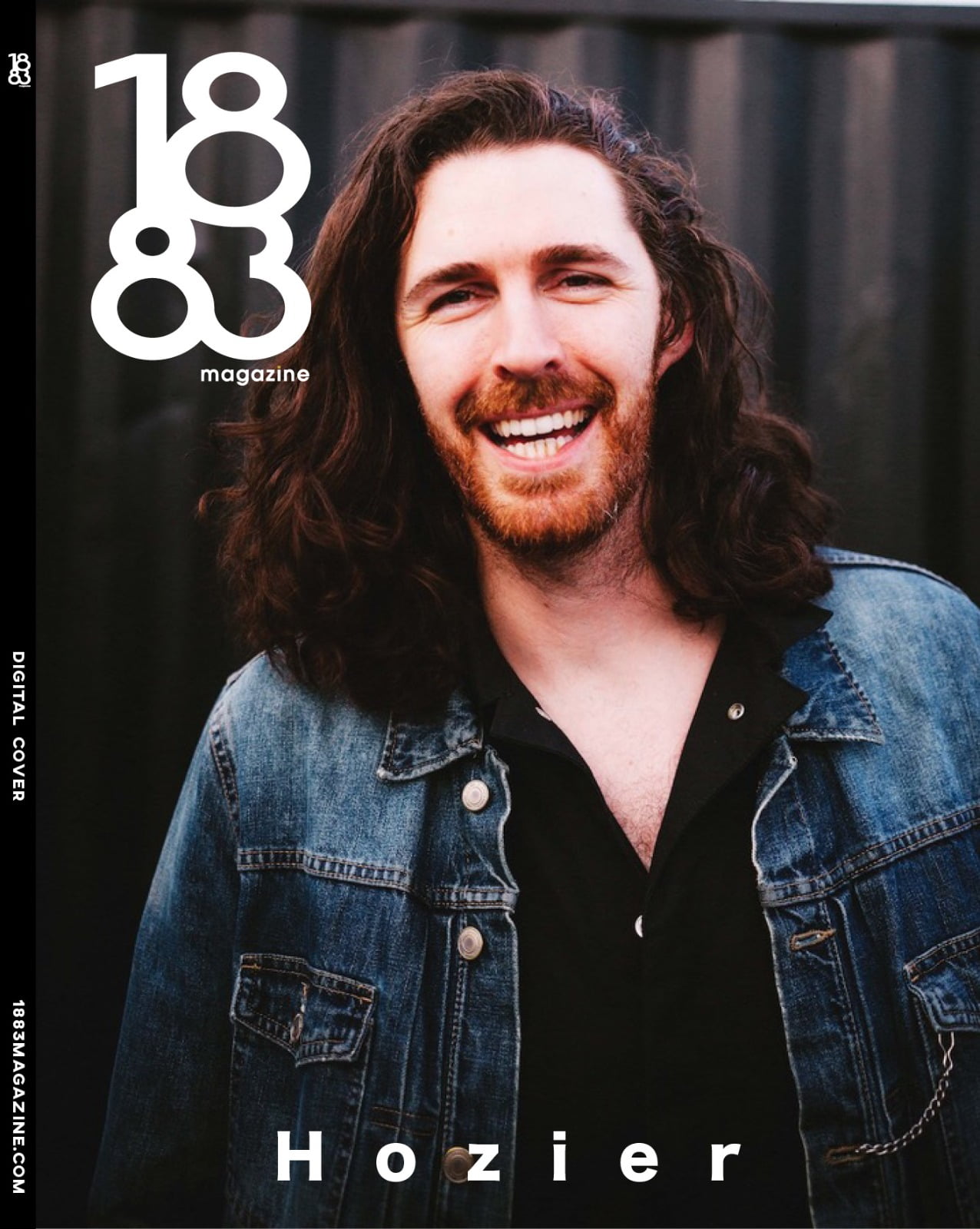

Hozier

On his highly anticipated third album Unreal Unearth, Hozier is making peace with the darkness and rediscovering the light.

For years, Andrew Hozier-Byrne opted to work more or less independently, and why wouldn’t he? His hit self-titled debut album, released in 2014, would take him around the globe and its follow-up, 2019’s Wasteland, Baby! would do just the same. Both became critically acclaimed collections of work, critics noting his unique ability to touch on societal and personal issues and blending everything from gospel to folk to pop-rock. But with his third album Unreal Unearth, penned during and following the pandemic, he let his guard down and embraced collaboration and connection after a bit too much time in solitude.

On Unreal Unearth, Hozier uses Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, an Italian narrative poem, as both a writing device and a text to pull inspiration from, mostly leaning on the first tale, Dante’s Inferno. As Dante journeys through Hell, he explores nine circles — Limbo, Lust, Gluttony, Greed, Wrath, Heresy, Violence, Fraud and Treachery — as a way to find his deceased beloved. With Unreal Unearth, Hozier embarks on his own journey through hell as he tries to make sense of his own experiences through myths and motifs. Across the 16 tracks, the themes are as modern today as they were when Dante first penned his poem — there’s loneliness and betrayal (“Unknown / Nth”), heartache and grief (“I, Carrion (Icarian)”). It’s not a lockdown album per se, but it is one about transforming oneself and rediscovering the light following the aftermath of going through hell — both metaphorically and literally.

Last week, Unreal Unearth became his first-ever number-one album in the UK. Hozier’s fans have an affinity with how he weaves an entire universe into his songs — every lyric is just as important and integral to the story as the next. It’s a connection that some artists can only dream of having with their fans, and it’s one Hozier doesn’t take for granted. When perusing timelines and forums, fans feverishly needle through the lyrics, attempting to make sense of those aforementioned myths and the journey he’s taking them on. He’s more than a “bog man” or a “forest king,” but an artist who deftly intertwines political issues with, at times, surreal imagery and sky-soaring sonics. He has a gift and we are lucky enough to be witness to it, a fan declares. Another finds comfort in “Butchered Tongue,” a song about Ireland’s history with colonialism, after feeling isolated from the place where they were born and, eventually, moved away from. Others listened to the album in a way that mimics Hozier’s own love of nature, listening to it on a mountain, in a forest, by the sea, or lying in the moss under some trees, as one Reddit user did. However and wherever people listened to it, it’s clear that Unreal Unearth is an album that both fans and Hozier himself needed.

To celebrate the release of Unreal Unearth, Hozier sits down with 1883 Magazine’s Kelsey Barnes to chat about the album, why he used Dante’s Inferno as a writing device, exploring darkness and uncovering the light, and more.

When Unreal Unearth is out, we will just be shy from the 10th anniversary of your first EP, Take Me To Church. When you think about then and now, how would you describe the way you’ve developed and grown as a songwriter and artist?

A lot of ways, especially with how I approach the writing of a song. I have not changed in what I try to get out of a song, if that makes sense, with the story that I try to get out of it and just what I look for in the broad scheme of it. I’ll say on this record I kind of let a few more people into the creation process more than I have done in the past, so that was a new experience to sort of jam with other musicians and share [the experience] with them. It was to work with musicians, to work with producers, and as a starting point to just throw ideas around in a way that I hadn’t done before. We would just jam and play music in a very old-school and traditional way, and take that as a starting point as a sonic and musical landscape. I would take those ideas away and create this sort of lyrical, melodic, and thematic content for it and still work with that still in a way that I always have done. The difference is that I would have this whole tapestry of sound to create with and share [with the musicians that worked with him] and that was really enjoyable.

Was that a response to the pandemic? Obviously, we couldn’t come together and work on music or even spend time with one another. Did you feel like you needed to connect with others again?

I think it was [a response]. Looking back, I think I had spent all the time alone that I ever would have the appetite for, and I say that as somebody who really craves time alone and also craves time alone to create. For me, creating music was always something I would do very much alone and needed space and time to think. So when I sort of ran out of hunger for that after two years, I had emptied my pockets of all the ideas that I could make on my own for that period. I was so activated with this great energy and I was ready to work with other people. I didn’t even know how much I missed this until I started, and then it was so exciting, very fulfilling, and very rewarding to create music with other people.

I feel like when a lot of artists start they work with lots of people and then, only when they are a few albums in, they feel like trying it out on their own. You did the opposite which is interesting — almost like you needed to keep it as close as possible until you were completely ready to just let go.

Yeah, I think for me it just took time to feel like I could let go of the reins a little bit and let people into that. I’ve been quite… I won’t say controlling, but I was just always very careful about making sure it sounded right. [Laughs]

On this album, you use Dante’s Inferno as a songwriting device to write about your own experiences. In the poem, Hell is depicted as nine circles of torment located within the Earth. At what point when creating this album did you decide to use this poem as a structure to lean on when developing these songs?

Quite early. In fact, there were songs in the early parts of the making of this album that leaned on the text nearly a little bit too much and too specifically. There’s a song on the cutting room floor called “Hymn to Virgil” and there is stuff that’s more specific in the text here and there. Even with “Francesca” I had something written for that song that was written in the idea of Dante’s interlocking triplets. But then I realised I kind of had to step back from that and just left it. It was becoming too musical theatre and so I just let the songs be the songs and trusted that they would. There are nods here and there, some of them are loose, and some of them are quite light. I sort of have to remind myself that this is a contemporary pop album and let the songs be what they need to be, and trust they’ll make sense in the journey of the record and not make it too specific to the text.

I was watching an interview that you did with Zach Sang and you were talking about “To Someone From a Warm Climate.” The song explores you revisiting a childhood memory of warming up a bed in an Irish winter compared to a bed already warmed — a formative memory compared to something new. While growing up, was it natural for you to find parallels in your own experiences through art, literature, and similar media?

Yeah, I think when you’re in the experience of living, there’s nothing you find remarkable about it. You know what I mean? It’s like anything — especially experiences that you look back on later on — that makes you think “Oh, God, that was very unusual.” It’s the stuff that maybe was very particular to your time and predicament with whatever you were going through in life. As you’re doing it, you don’t regard it as something big and you’re not thinking about it all that much. You’re just in the process of getting through it. So, that was kind of the first [with “To Someone From a Warm Climate”] and there’s maybe some other songs where I’ve looked back at like childhood stuff and big specific moments you remember. I think it’s more of finding these little things that resonate with each other in memory and things you experience that somehow hold together and you make the connections and explore them.

Yeah. I always love it when something that seems meaningless, like a cold bed in childhood, can find its way through to somebody’s memory at like 32, or 33.

Yeah, I agree. I think talking about the weather earlier on, you don’t realise just how formative the climate is and how it sort of gets into your bones. It’s like a lot of the conditions and I think there’s a line in “De Selby” and it says “what you’re given and what you live in.” I suppose it’s given in a cosmic sense like the place that you find yourself in this life and what you live in finds a way to live in you — you can’t really separate the kind of things that pervade and penetrate you, they just become a part of you. I think it’s the same with it, it could be the weather or it could be as simple as your experience of going to sleep on a cold bed. It’s not bad or good or anything, it’s just what symbolises that experience for you.

You touched on “De Selby” who is a fictional character created by Flann O’Brien for his novel The Third Policeman who believed human existence was “a succession of static experiences each infinitely brief” and “a journey is a hallucination.” How does “De Selby” fit into the nine circles and what was the writing process for these two songs? To me, they seem like two sides of the same coin which is why they are part one and two.

They kind of are two sides of the same coin and they explore the same idea, but one explores it in a sort of an internal personal way and then the other slightly into more of a romantic way. I think “De Selby” is a descent song if that makes sense. It’s about reflecting on darkness and entering into a very, very dark space and reflecting upon that. And then I try to bookend the album where there’s a descent and an ascent with “First Light” being the last song that means sort of is returning to the sky again. But “De Selby” is really just the descent and — are you okay if I give you a spoiler?

[Laughs] It’s all good!

Okay, good. He is a character in the footnotes through this book, which is an Alice in Wonderland of the 20th Century piece of classic Irish literature. It’s a surrealist novel. It’s a long tale of a man who is confronted with the infinite and all the way along, he’s thinking to himself about how he’s reminded of the writing of himself. Who is this lunatic? He’s a fictional philosopher. He’s fictional but, in this book, he’s somewhat of a figure of interest for the main character of the book. Then he’s this sort of lunatic philosopher genius, who has a sort of a childlike logic about how the world works and claims to prove it. As this man walks through the world, he sort of starts to see the world like the show. The TV show LOST actually included this in the show.

Oh, I loved that show but I watched it when I was younger so I don’t think I clued in and realised this! [Laughs]

[Laughs] Yeah! There’s actually a scene, I remember people sort of caught onto it, where a character was reading the book and there are references to it [in the show]. I don’t want to spoil it if you end up reading it, but it is the exploration of the entry into darkness, to the underworld or the afterlife, if that makes sense. It’s the idea of entering into sheer blackness. De Selby in the book thinks, as an example, that nighttime is not an absence of light — that the light doesn’t go anywhere, and the sky is what you would call black air. There’s just a new substance that we call darkness that we can be lost in.

But it was more fun to explore that — the afterlife and entering the sheer pitch blackness — and finding what is freeing about that. There’s an Irish philosopher called John Moriarty who reflected on that as well and there was the influence of that on part one, in particular. In the darkness, you are lost within in a very freeing way. You can’t see your hands in front of your face, it’s like your hands are gone and you cannot tell the difference between you and the state around you. You internalise that in a very real sense.

Part two reflects on, in a more romantic sense, this idea that you can’t see where one person begins and where you end. It’s about sitting and allowing that to become a reality for a moment. It’s an internal reflection and exploring and entering that dream vision.

Yeah, the note that I made for “First Light” is envisioning someone coming out of the darkness — “One bright morning/changes all things” and “Like I lived my whole life/before the first light.” I love that the album is bookended in that way — this idea of going on a journey and coming out the other side changed.

Thank you, I really appreciate it and hope it sounds that way.

This album feels conversational while still maintaining a degree of introspection and reflection. How do you carve out a space for yourself to explore in your lyrics and work to help process what’s in your mind while still leaving room for your listeners to find themselves in the music as well?

I just trust that people will find what they want. I don’t know if I try to deliberately carve out space because it would feel inauthentic if I did, but I think writing music around any human experience helps make it universal and makes you feel less alone. I trust that people will find themselves in the music and if they don’t, that’s fine.

“Butchered Tongue” is quite a powerful song. I know in a past interview you said it might be a little uncomfortable for people to listen to due to the violence it describes and touching on the suppression of the Irish Rebellion of 1798. The lyrics “And as a young man blessed to pass so many road signs/And have my foreign ears made fresh again/On each unlikely sound” and “In some town that just means home to them/With no translator left to sound/A butchered tongue still singing here above the ground” tie your travels with your gratitude for the preservation of the Irish language. What was the writing process like for that track in particular?

Thank you again. I knew what I wanted to achieve with this song. I think, initially, it was going to be a longer piece of music. It did take me a while, but I knew I had a few lines I wanted to explore and settled on it being a shorter two-verse song. I won’t say it was difficult, but it was a challenge to make sense of how I could say what that song was trying to say.

There’s a lot of sorrow and it’s kind of a lament. It touches on a lot of violence and tragedy and a great deal of loss, like a loss of language and loss of culture. But you still have this shred of gratitude and appreciation for the lived experience of people who are born in places that are based upon the colonial satellite just home for one person couldn’t be. So, trying to balance all of those things, all of those outlooks, was a challenge for sure.

In a past podcast, you said you view songs as keyholes, as if they are historical documents. Now that we’re on the third album, I was thinking about your legacy and impact. I don’t know if this was the intent, but one reading of your album cover art made me think that even after you’re gone, your music will live on — as you’re buried, your mouth/voice is the thing that survives. Is your legacy something that you think about?

I think the less I think about it, the happier I am [laughs]. I’m sure all artists do [think about legacy] to a degree because I think you want to leave behind something worth saying or that was worth making. I don’t know if I was thinking of it in the sense of my mortality, but the album is a rightful reference to mortality and a lot of the songs that didn’t make the album were reflections of loss. I was thinking about watching above the ground after somebody’s gone and the mouth is in a dark space. I sort of view the songs as each one being a different voice as a nod to the inferno and how, you know, Dante is going around each circle and having another conversation with another person and their experience.

In “Son of Nyx,” it does sound like there’s like a little bit of a change. I feel like it’s placed right in the middle and it does seem like there’s a tone change after the rest of the album. I don’t know tons about Greek mythology, but I researched Goddesses and personification of the night. What was it about that song that made you want to make it, for the most part, entirely instrumental?

There’s a storyline with it. The piano piece that you hear there, that’s a phone memo that a dear friend and collaborator Alex Ryan, a friend of mine I met in college when I was a music student there for a moment. He wrote that piano piece after the passing of his father and I asked him if he would mind if I included it on the album in some way. It was significant in two ways. The first is because, in Greek mythology, Charon is a psychopomp, the ferryman of Hades, the Greek underworld, and he brings spirits to cross over. He’s also the son of Erebus and Night, so it appropriately fits. It also was significant that a friend who is the son of Nick would be an appropriate tribute to Alex and his father. We just kept it as an instrumental, albeit there are little sort of distorted phrases from the rest of the album that you can hear come and go.

Lastly, I do want to touch on your relationship with your listeners who are incredibly engaged in your work. I had so much fun diving into Twitter and Reddit to read all of their thoughts on the album. Earlier this year you put up a poll on Twitter asking for their thoughts on album length and their preference on exploring a larger body of work vs. a shorter one and I loved the responses. Why is it important for you to get a sense of what they are thinking or feeling when developing an album?

[Laughs] Yeah, you have so many discussions in those final decisions of making an album. A lot of producers and a lot of musicians usually just do a quick 10-song thing. Me, as an artist, I feel like I just always want to share everything that I can and just let people decide what their favourite is, you know what I mean? There is so much stuff that I would just like to share and show people. The industry sometimes slows you down and makes it more complicated when you, as a writer, just want to write something and show it to people. In a way, I was looking for some encouragement [when posting that Twitter poll] and I’m glad I found it. Sometimes you need it to get other people to understand that there are people who would rather hear more and then just figure out what they like instead of being given a smaller amount of work and then have to wait for another release.

The way I view it, either way, people are investing in something and they’re investing their time. If they care that much, especially in this day and age and under current conditions, and they are somebody who puts their hands in their pocket and spends money on albums, then that is a big deal. And if they’re doing that, I’d rather they have a generous body of work to explore and enjoy. I think it was also good to know that the albums we’re releasing have always been quite sizable, like 15 tracks or 16 tracks, but it was good to get a sense that there’s still hunger for that. There’s still an appreciation for that.

I agree, and fans love devouring every bit of every song, album and universe you create with every album release. It’s been a pleasure, Andrew. I know you’re so busy so thank you for your time and thank you for creating such a beautiful album, I feel lucky I’ve been able to listen to it so early in advance.

No, thank you for your time and your kind words.

Hozier’s new album Unreal Unearth is out now.

Interview Kelsey Barnes

Cover Photography Muriel Margaret

Live Photography Natt Lim

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.