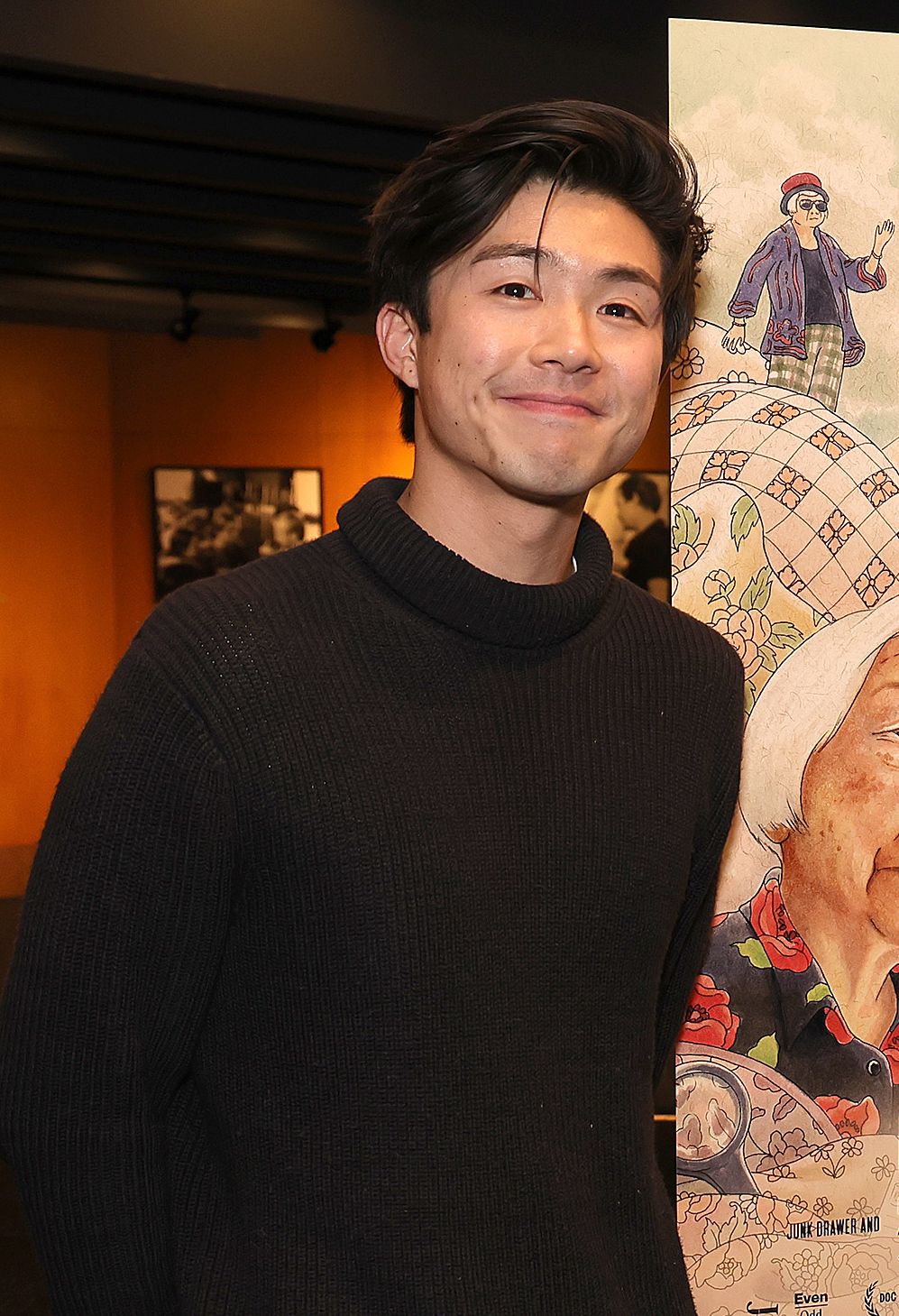

Makoto Shinkai

Makoto Shinkai has achieved something few animators have — household name status. His 2016 critically acclaimed film Your Name was followed with Weathering With You. Now, completing his trifecta of environmental-themed stories is Suzume: a deeply moving and incomparable work about grief, the fragility of nature, and all of our resilience.

We follow the titular heroine, a high school student still reeling from the death of her mother in the very real Tohoku tsunami of 2011, whose encounter with a handsome stranger named Souta sets her on a path to save Japan. Over the course of her Eastward journey, they meet all manner of obstacles, befriend various women along the way, and all the while Suzume has to confront the fragmented memories of her grief.

Suzume is being heralded as one of Shinkai’s best, and it’s no wonder why. Having honed his animation skills since working as a video game animator with Nihon Falcom in 1996. Now, Shinkai’s attention turns both inwards and outwards in one of his most introspective and relatable films to date.

One of the most stark images from Suzume is when you see ships sitting on top of buildings — and this was a real image from the aftermath of the Tohoku tsunami. But it was reminiscent of seeing cars on top of houses on Staten Island after hurricane Sandy. Were you cognisant of the ways in which those images resonate beyond the Japanese audience?

When I’m making a film I’m only really thinking about the domestic market. I’m making a film for Japanese people to watch. I always think that if you make something for the person right next to you, it’ll get through to other people as well.

So if I’m making something for Japanese people, it’ll end up reaching people in other countries as well. And I believe that — I’ve never doubted that — and so I’ve never really thought there was a need to think about the international market when I’m making a film. I hope that if I dig deep into the place where I am right now, then that will get across.

Is there an element of frustration with that question? People often ask if you’re worried that your messages will translate to a Western audience, as if the Western point of view is the default.

Not so much that, but what I am fed up with being asked about is that foreign media always insist on asking me about [and comparing me to] Hayao Miyazaki.

I do feel though that the West is the default. And I feel like this is where films are born and where the critical standard is — it’s set in Los Angeles and in Berlin and a number of other film festivals. I feel like film belongs to them and not to me.

But to be honest, I’m not that interested in what the industry says. I want my films to be entertaining. I want people to enjoy them. Both people in Japan and all the fans that I now have in other countries. The audience is the most important thing for me. Not whether I match up to the global standard. I don’t feel like I need to play that game. Although I realise that for sales, those awards and the recognition and the festivals are important. I trust my overseas distributors and leave that to them.

Suzume is a very woman-centred story, and as a woman who lost a parent it’s especially easy to relate to. Did you worry about what the reaction from fans would be, having a heroine who takes charge of the story?

I wasn’t really worried about that. What I had in mind when I was making this was Hayao Miyazaki’s — and it’s okay for me to bring him up! — Kiki’s Delivery Service, which of course is a story about a young woman who meets women of different ages, all of whom could be her future self.

I watched that in high school. I found it very moving. It was a big hit throughout Japan. And if I could watch that as a young high school boy and be moved by that story, then I didn’t see any problem with making a female protagonist.

You talked in your mini-documentary about living through the 2011 earthquake and using your tools as a filmmaker to help do something positive out of that, but is there also an internal processing of your own emotions? Using filmmaking as a tool not just for the public but for yourself, to process the things that you’ve lived through?

I think ultimately, I make films for myself. I know I say in these interviews and in events that I’m making mass entertainment and I want the audience to enjoy it and that’s true. But ultimately I feel like I’m making them for myself. That scene that you said you cried at, where Suzume goes back and talks to her younger self… That’s how I feel when I’m making a film.

I’m thinking how would I feel if I’d seen this as a child? How would I feel if I saw Suzume when I was in high school? I want to be impressed and moved, and to show myself that this is a world worth growing up in.

Suzume is out in UK and Irish cinemas on April 14.

Interview Gabriella Geisinger