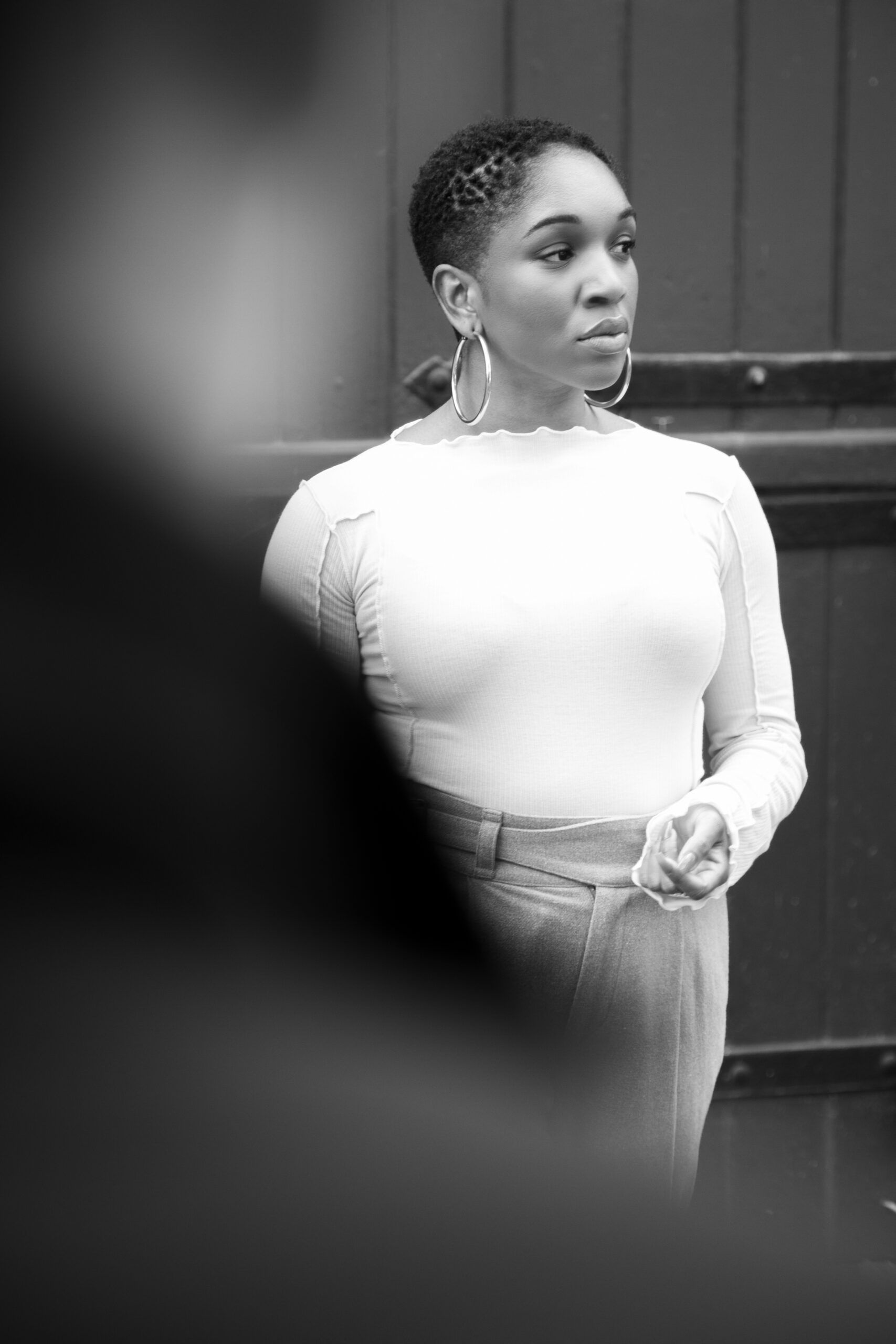

Actress, playwright, director and producer Cherrelle Skeete is a force to be reckoned with.

Since starring in the likes of The Midwich Cuckoos, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, and HANNA, Cherrelle Skeete has been solidifying herself as both an actress and a powerful voice within the film industry to keep one’s eyes on. After studying at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, Skeete has been, without consciously realizing it or not, tying together projects across stage, screen, radio and video games that all have one goal in mind: to showcase the importance of authentic, truthful representation. Most recently she created Blacktress, an organization with Black womxn creatives at the forefront with Skeete at the helm.

In conversation with 1883 Cherrelle Skeete chats about her grassroots organization Blacktress, her upcoming work, and more.

You do it all — you’re a stage, screen, and voice-over actor, playwright, director, producer. And you grew up in Birmingham, so how did your upbringing help hone your interest in the career trajectory you’re on right now?

Birmingham is a multi-cultural city, it’s the Second City, so nowhere near as big as London. We’re based in the Midlands in the middle of the country. Around the 50s, 60s, 70s, [there was] massive migration from the Caribbean and India. I grew up in the very grassroots Jamaican, Caribbean, Garvey, Black liberation background. There were always talent shows and things constantly going on, like cultural celebrations to bring people together. I started with a dance group with three of us making up routines and then, over one summer, we were teaching some other young people and they said they wanted me to stay and we eventually grew to 30 people.

I suppose that, as a young person, managing a company of other young people develops those skills along the way of directing and figuring out funding applications. I was a young person myself being thrown in the deep end. Being a young person from the community, from the inner city, and just wanting to learn and loving art and loving expression and seeing how art literally saves lives. Like it, it literally saves lives. I’ve seen it with my own eyes. In that kind of environment, it’s given people a space to belong; it’s given escapism when it’s been hard for them at home and it’s helped them understand who they are. Even if they don’t know who they are, they’re on the journey of figuring it out. I know that was really important before I went to, I suppose, a very different environment of a drama school. I’m really fortunate I had that foundation because I was learning about Phillis Wheatley and Marcus Garvey and the Harlem Renaissance. I understood theatre and art and film from a perspective where people look like me. I was then taken into an environment where it was the antithesis where I was reading about dead white men. I’m really fortunate to have had the dual…

Kind of a dichotomy of it.

Yeah, exactly. Being able to take bits of each thing to be able to create my own. With the way things are at the moment, I don’t know if the linear career even exists anymore. It’s the survival of artists. For me, I’m a storyteller; anything that I do, it’s always about stories. Whether I’m curating an event, it’s about bringing people together to share their stories or a social. Whether I’m directing, then I’m facilitating a space where I’ve got the blueprint, which is the script to tell that story. If I’m acting, then I’m embodying a character to tell that story. Everything I do is fundamentally about storytelling and, obviously, we give it all these different names, depending on whatever form it’s in. It’s all the same thing, even down to the way that I dress. You know, there’s a story. We had a whole conversation about our hair. There’s a whole story in it and that’s what connects us as people. It lifts my vibrations.

There was something Billy Porter talked about the other day about being able to do it all. He said “Listen, this is how I survived. You know, I am classically trained. I can do this. I can do that. But that’s how I’ve been able to sustain myself as an artist all these years.” People only know about him now, but he’s been in these streets. That’s the thing—specifically as a Black actor where maybe you’re not going to be the lead role straight away. Best believe you’ve got to make sure that you are fulfilling yourself, you’re nourishing yourself as an artist and that you can, you have the ability to survive.

The fact that you came from an environment that supported that kind of journey for you, gave you all these tools and all these resources to figure that out, especially from a young age. Art saved me. Being in children’s theatre as a teenager. I did not have a great home environment, so being able to have that escapism and kind of that found family, I feel like that’s very important. Just hearing that you actually came from an environment that really facilitated that for you is amazing.

It’s quintessential of Caribbean culture. When going to drama school, I saw it as a separate thing. They were like, “Okay, now we’re doing this, now we’re doing this, now we’re doing this.” Within the Caribbean and very African culture, it’s intertwined. A lot of people ask me if anyone in my family is an actor which they are not per se, but they’re brilliant storytellers. They’re Caribbean; everything is loud, everything is seasoned, over the top. There isn’t a small way of doing anything. They all pick up a guitar. If there’s a song playing and they’re playing Soca, there’s always something going. There’s always food, music, dancing, storytelling, that’s just it. Every single event, birth, life, death. That’s just how it is.

You had the unique experience of getting to originate the role of Rose Granger-Weasley in the West End production of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. That added to the Harry Potter canon racial diversity with a black Hermione and a Black Rose. What did that mean for you, especially coming from the environment that you came from, to be a part of this kind of iconic thing and add something new to that?

I knew it was going to be something special because of the connection people have with the story. I had lots of friends who, when they found out that I was playing that role, they were literally crying,“Oh my God, I feel seen. I really saw myself at Hogwarts, this little black witch running around. And now it’s you. Oh my gosh, you don’t understand. I feel seen as a lover of these stories.” For me, it’s for people like that.

I connected with this teacher who literally slid in the DMs on Instagram. She teaches in a very rural part of Calcutta in India at a girls’ school in this little village. She asked for me to jump on Skype and basically arranged a talk with these girls who were reading the books at the time. These are girls that can only school for half a day because then they have to go home to help their parents. There’s also obviously the whole caste system in India and these are dark-skinned Indian girls who are acknowledging and seeing parts of themselves in me and Noma [Dumezweni] playing these characters.

For me, knowing that these girls, even if they’re not going to watch the show and just reading the books with their teacher and they’re writing songs, I knew that this is who it’s for. The fact that they know, in India, even for these girls to be at school is revolutionary where they come from and knowing that these darker-skinned women are playing these roles they love is the most powerful thing. There are people that can afford the tickets to sit down and watch and then there are going to be people that, you know, realistically, the way they can connect to literally through reading the book with their teacher. This teacher was able to reach out to me. This is what I mean when I say art changes lives. It can inspire and can go beyond me playing an important role because it takes it outside of me. It means it’s not really about me, it’s about the work, and making sure that this work can touch as many people as possible if it means that it’s going to empower them or make them feel stronger and make them feel seen. That’s always the mission.

And you’re still writing your debut play, right?

I am. The process of writing is such a different hat to acting and such a different hat to directing. It’s a very solitary space. I think sometimes, speaking to other writers as well, some of the themes that have come up, I feel like I’ve had to grow in order to understand the themes. It was writing itself and then I just got blocked. It’s about two communities. I remember feeling really like I knew the story of one community because it was the one I was familiar with because it’s the one I come from. But then this other community, I thought, “Oh, I don’t want to misrepresent them.” I want to make sure I’m handling the language because a lot of what they say is in a different language. I wanted to make sure that I’m representing that culture with the same respect and dignity that I would approach my own. That means learning, speaking to people and that takes a bit of time. I suppose this fear around that as well because I want to represent it in the best possible way. It’s taken time but I’m actually touching base with it because I’ve wrapped now on The Midwich Cuckoos. I’m going to be getting back on that.

What are the main themes that you feel like you’re going to touch on with this play?

Stuff around immigration, specifically in the UK. The cross-cultural exchanges with migrant communities, ones that are obviously very different, and then the similar experiences. I’m really interested in where we look at ourselves and think someone is one thing and actually flipping it on its head and seeing they are something completely different. shit!” I want us to look at each other and see each other as just the connection of humanity. I also found that I write a lot about old ladies, so there’s always an older Jamaican woman that’s in my plays. One of my central characters is a Jamaican woman, which I think possibly is a version of my grandma or other old women that I’ve come across. My mom was a hairdresser, so I was around old ladies a lot when they would get that little press and curl. I always have versions of those women in my head and I feel like I’m an old soul anyway.

It’s about these two families around the Windrush Scandal. A lot of those people that came over who were children of that generation that came over to England post-World War, who were on their parents’ passports and documents disappeared. What’s happened to them now? There’s been a lot of campaigning where people have been fighting and working and living their lives, paying tax, and then they’re told that they have to go back to their country of origin even though they’ve not been there. Their lives, they’ve just been deleted. The state has just left them with a lack of dignity. The main antagonist is probably going to be what the UK has done to these people and then how they’ve been able to overcome that as a community.

In Birmingham, within areas like Handsworth, you’ll see that depending on what’s happening politically. I remember there were Bosnians, there will be Somali, there will be Polish, there would be obviously the Jamaican, different smaller island people there. You would have the Indian and Pakistanis in one area and you would see them come and you would see them go. As things have gotten better and they’ve been able to build themselves up, they’ve gone back home. I’m interested in how these communities, who come through migration, are changing very quickly. Borders are going up, borders are going down, and how these communities interact with each other or don’t interact with each other. They’re bringing the same culture that they’ve had in their country to the UK. I’m interested in that cross-cultural dialogue in a British environment.

Sounds like a little bit of the Diaspora is involved with that, especially if they can bring their culture, but they’re separated from the geographical origins of that culture.

Yeah, that’s it. I find it fascinating within Caribbean culture because it’s always asking “is Creole really a mix of things that we remember from being in Africa and things that we’ve created anew and things that we’ve held on from being enslaved but we’ve turned on its head and made it our own thing?” I think being Caribbean-British, it’s always about kind of creating anew and I think there are other cultures doing that, they’re pulling from that the Mother culture, their place of origin. Then there is a feeling of knowing you’re having a very British experience, which kind of doesn’t correlate with some of the things culturally that we would do. It’s cutting ties with certain things but bringing certain things with us and letting certain things go. I’m kind of trying to throw all those things into play because it obviously brings up stuff about me and my own identity.

I haven’t actually read it for a while purposefully- There was a particular woman called Paulette Wilson, I have to say her name. She was a cook from an area called Wolverhampton, which is not far from Birmingham, and she was taken to a detention centre to be deported. I read her story and I was really, really inspired by her. Sadly, she passed away but she was campaigning for people like herself—those who have been taxpayers that have worked really hard and have been brutalized and victimized. The absolute inhumanity of literally being pushed aside as not human. The moment you take away that person’s ability to work to be able to feed themselves… It’s just awful. I’ve seen it with my own eyes and the impact that has. Sadly, quite a lot of these people are passing away. I do think it’s to do with the stress of not knowing whether they’re going to be taken away from their families

Yes, of course. Do you have a title? Is it titled?

I have a working title. It’s called Happy Snaps. This whole thing is involving memories, so we go back and forth in time across British history where migrant communities have been here before. The hope is that we can kind of cross those bridges. I want their stories to be told too. My partner was like, “Cherrelle, get done by the end of this year!” I was like, Yes, you’re right. I’m so, so close to this time.

As someone who grew up doing theatre, I’m sure acting on-screen works very different muscles. How do you adapt the skills you use on stage for the camera for a series like Hanna and The Midwich Cuckoos?

I’ve had to learn through doing. My heart has been the stage. That’s where I’ve learned my craft and it’s been great—it’s a different beast. I suppose what I’ve learned is if I’m playing to an audience of 3000, which is proscenium wide, it’s very technical. The audience now is a few centimetres away, and what was meters and meters wide is now—you have to imagine them all being concentrated down that lens. A lot of it is to do with making sure your friend is your focus puller because you want to be in focus, so you’ve got to hit marks. I like to build a dialogue with all the people that I’m working with in terms of like, the DOP, the director, having a conversation with what they are trying to achieve. As an actor, I’m trying to carve that as part of my process and trying to understand what is that you’re trying to achieve. Because as an actor, my journey is this, but the environment that they’re creating might be something completely contradictory. Sometimes it’s helpful to know, sometimes it’s not, but to make sure that I’m supporting the vision that is being created by all these other many different departments… I try to infuse that sense of collaboration for myself.

I’m still learning, so I haven’t got a definite answer because each job requires different things. When I did Call the Midwife, I had to understand what I had to bring to the role in order to support this particular character, and I knew that I had to stay in character. Therefore, it meant that I had to have a conversation with all the different departments. In between takes the could move around me as opposed to me jumping out. For me, I want to keep collaborating. The more voices that we have that are creating and adding and layering, the more nuanced and interesting the work is. Everyone’s bringing something. Obviously, I’m embodying this particular character, but if I know there’s a light that’s coming from a certain angle, I can make sure that I’m angling in my body, or if we’re working shadows, I know I need to hit this mark. There’s so much more to learn and it’s literally discovered through doing.

How do you distill all of that when you’re doing voice-over work for a video game or an audiobook, where your voice is the only vehicle for all of the emotion you have to express, but then also all of that collaboration in telling the story as best as you can?

I always would start with breath and I also think about where the character is rooted. Then, that will tell me where to place vocally pitch-wise, whether that person has a nasal quality or it’s rooted here. It will also be where the root of the character is. Sometimes it’s just one simple choice where maybe the character is very introverted. Straight away it changes the quality, so you don’t even have to do a lot to try not to pinpoint every single aspect of a voice. Sometimes it is required. Sometimes it’s just instinct like you’ll read a character and you’re like, “Oh yeah, I know who this is”, and someone in the back of your mind who I suppose you’re channelling as you’re saying the lines.

Being classically trained as well as you know where you came from just in the thick of it, what are a couple of lessons that you’ve got from your schooling at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama that you feel like you might not have if you hadn’t gone to school? Do you think that there are a couple of lessons that you’ve got from your schooling specifically?

My difference is my superpower. I know there are a lot of things that I’ve learned within my training at that school that I suppose is bog-standard, that when you have a conservatoire training, you do Shakespeare, you will do some Russian plays. I think I spent a lot of time understanding how different I was and being scared of that. By the way that I speak or the way that my body is in comparison to what I’d seen at that time. Obviously, the generation of actors now, they’re having a different experience, which is great. I mean, they’ll have new issues, which will be interesting to find out later on down the line. But I spent a lot of time trying to fit into this cookie mold, which actually doesn’t exist. It doesn’t exist and actually doesn’t serve anybody. The moment that I really connected with the things that make me come alive and the things that I really enjoy, the things that maybe not everyone else will connect with was the most important thing for me.

It also exposed me to classism as well. I was coming from a hood background, very Blackity-black, very Caribbean, very Birmingham. London has had a different way about them, and I think that was like a whole new culture that I was exposed to that was about theatre. It was the tip of the iceberg and it was almost like learning that this exists. It was a really big learning experience for me in that sort of a lesson of classism, racism, elitism and then being like, “Well, where do I sit within this?” At the whole of my own personal journey has been making sure that I’m not being phased or pulled in by those structures or systems and just being like, “Well, this is my lane and all of that stuff that’s going to exist. Well, I don’t necessarily have to subscribe to it in that same way.” And that’s a daily thing.

That way, you feel like you don’t have to perpetuate it going forward and in your work?

That’s it. That brings up all these things that I know a lot of us experience, which is this imposter syndrome. We feel like what we have to fit into this mold which is rubbish, you know? I’m really glad that I left Birmingham to go to drama school because it opened my world. It actually made me value my roots even more. So I’ve got to shout out people like Miss Louise Bennett [Coverley], who was the first black person, the first person of colour ever to go to RADA, the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. It was when I was at drama school when we were looking at poetry and I was like, “Let me look at someone who’s from the Caribbean” and I really started to study her work and it was so revolutionary for her in the 30s or 40s. She got a scholarship to come to London to do this course at RADA, the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. Then she went back to Jamaica and then was part of the artist movement towards independence. She vowed to only ever write in Patois because she wanted Jamaicans to reconnect with their Jamaican identity and to be proud of who they are.

So, every Saturday, when my mom lived in Jamaica, she would watch her on the TV show. She would tell Anansi stories and folk tales, and at a glance, you would be like, “Who is this big woman just telling all these stories?” But you have no idea how revolutionary that was at that time. She could do it or she would perform Shakespeare. She would do a lot of curtain raiser, so she would come on stage and perform before the big play would happen. She performed at the National Theater and she would speak in Patois only. So you’d have a lot of English people confused, not being able to understand her. But what I admire about her is she can speak receipt pronunciation, perfect to a T. But it was always about her conscientiously going into spaces and bringing every aspect of who she is to every single space. She can switch you up. You know, we code-switch all the time. But she was very conscious to be like, OK, I really want to do this for my people. I want people to know that we can be, within our language, smart because she studied Shakespeare. She will compare the way that Jamaican parables or sayings are put together, the syntax in the same way that Shakespeare would put something together. She’s trying to say, actually, we have value in who we are and language is so important. So it was really, really, really important towards the cultural identity, especially post-Independence in Jamaica to have someone like her, who has been to England and she’s got their training. She’s got the training that I’ve had and she’s decided to be like, Okay, well, I want to be part of the movement of the healing of my island. And I just think that’s amazing.

Well, that is a perfect segue way because we are absolutely going to talk about Blacktress UK, which you co-founded in 2017. And this is an advocacy, community, grassroots organization you co-founded with one of your partners. I’m sure what started up as community-driven meet-ups have been affected by the pandemic and restrictions. How did your programming shift? And how is it adapted since some of those restrictions have loosened?

With everything that was happening, it was really important for us to still try and stay connected. A lot of the work that we do is actually about bringing people together in physical spaces. It’s about tackling this whole feeling of being the only one. No, you’re not—you’re not the only Black actress out there. We are across diasporas and languages and different tribes, and differently-abled and orientations and even across gender and where people sit on the gender spectrum. We got an offer to get a commission from this company called Grand Junction, which is a really beautiful gothic theatre space in Paddington in London. They were doing a festival called “Comfort and Courage” about taking people on a journey where you can sit from the comfort of your own home, but speaking about what courage is for you. We decided we’re going to curate an event with this festival online, it’s going to be streamed. We had various artists who are part of our network who would have usually been performing on stage at this moment. The theatres are dark, but also a lot of the actresses, like myself, multi-hyphenated run grassroots organizations themselves. So I thought, You know what? I want to highlight the work of these incredible women, and that’s what we did. Whilst the stage is dark and not many shows were in production at the time, it was about talking about the other work that’s happening that doesn’t necessarily get the stage importance that doesn’t get spoken about as much because it’s not sexy.

Grassroots work isn’t always sexy and it’s not for every actor. I wanted to highlight the work that actually is fundamental during this time when people are feeling so isolated and that work is still continuing, even though people aren’t in the West End right now. Once the restrictions started to loosen, I was brought on to direct at this festival called Six Artists In Search of a Play at the Almeida Theater. I was then brought on to look at the theatrical traditions from the Caribbean. Whenever I get involved in a project and whenever a venue contacts me, I’m like, “You know, I’m bringing Blacktress, right? It’s a Blacktress production.” We had a coordinator who does a lot of the admin for Blacktress. We basically just brought some of the network’s incredible actresses to perform in the poetry share-ins. By this point I think we had social distancing within the theatre, so this was kind of the first wave of theatre being open, but in just small capacities. So it’s been really, really careful. And also, I understand that with the way that COVID has affected people in different ways, people have very different ideas and politics around all of it, so it’s been hard. We’ve been on very much a hiatus this year because I wanted things to settle because we were also safeguarding. We’ve got vulnerable people at home as well, so that’s how it’s affecting me personally. We want to have a social towards the end of the year just to kind of get people together, look people in the eye, and also to celebrate our award as well.

We’re not as busy as we would have been over the time period. It’s been a lot quieter. It’s been a lot more selective, which I think that’s okay. And also the thing I can imagine for myself, and any multi-hyphenate artist, we are constantly battling burnout. Burnout is a thing, especially as a Black woman. We have the backbones of a lot of families, communities, organizations, cultures, everything. We’re the ones who are driving things forward. I think it’s really important that we don’t get pulled into this capitalist idea that if we are resting, then we punish ourselves and punish and judge other people for taking time out. So there’s that as well. Just being a lot more selective and mindful. I am very proud to see the changes and shifts since Blacktress’ conception, even just at the time calling an organization Blacktress.

I’m sure Blacktress has probably been a saving grace for some people, especially with you guys being awarded in terms of mental health. People not being able to do the work that they kind of put their self-value into and are like, even though everything’s kind of on pause, you’re still who you are at your core and having a community that reminds these women of that. Like, you might have to find a side gig or you might have to cultivate a different skill during this time while your main career is on pause due to these restrictions…but your core value is not in what you do, your core value is in who you are. And I’m sure that’s been very, very critical and probably life-changing for some of these women during this time.

It’s been life-changing for me. We’ve had conversations around voice and dialect. I think that particular workshop was really powerful because the work that we’re approaching is, yes, as actors, we’re interested in voices and dialects and pitch and doing accents and whatever, but it was more about raising a level of consciousness to how we’ve used our voice. When we’ve altered and shape-shifted. So it was great hearing conversations of people who said, you know, back when I was growing up, it wasn’t cool to be African. So I used to try and put on a Jamaican accent, and then open a dialogue about that. We spoke about how black women are the backgrounds of families and communities and culture and all of that. And this one young woman she was my mother and she had recently lost her mother. She was considering drama school, and she wasn’t sure whether she was going to go to drama school because she was so burnt out from advocating for her mom to medical professionals, who were supposed to be supporting her. So she was really burnt out. And actually, through that conversation, there are always tears because whenever you get black women together, that always leads to a place of healing. It’s for all of us to uphold this safe space, whatever that means, and that we hold each other’s stories and we just need to be given the space and time to do the work. And it just happens. That’s literally what we do. We facilitate that. We get the rooms, we organize the time and the dates. We say this is the theme, and then we just try and guide those stories. It’s for people’s stories to be heard.

It was really interesting because during the rise of BLM, I had to stop and ask if I should be doing something different. I had to remind myself before all of this was a thing, I’ve been doing the work; I’ve been kind of talking about the roles and talking about women’s anger, Black women’s anger, creating spaces to have those conversations, looking at the process, looking at drama therapy and Black trauma within stories. We’ve been cultivating these conversations already. It’s the rest of the industry and the rest of the world that have had to catch up.

We’re a movement in the generation of the internet and Twitter and Instagram and social media platforms, but there are other Black women artist groups that have been going before us that I have to shout out as well. People like Sharon Duncan-Brewster and Natasha Gordon, who created spaces for women to create and write their work and to just have the resilience to keep going when people weren’t hiring them. This would have been like back in the earlier 2000s and 90s and stuff. It just mirrors the work that was happening with people like Maya Angelou and James Baldwin and these pockets of people, who are literally just each other’s cheerleaders when you got really, really hard. It’s the same thing of coming together and figuring things out and supporting one another and healing each other’s wounds. It’s literally that moment in Hidden Figures when she walks that room and just the image of all of those other Black women at their typewriters in the run-down room. She walks into the space and Taraji [P. Henson’s character] gets a chair held out for her, and she sits down. She ain’t alone. No, she’s not alone. That’s the power of community. You know, Audre Lorde talks about that: where there is a community, there is liberation.

Lastly, as somebody who’s multi-hyphenate, you’re not beholden to just one role, one focus. What haven’t you done that you want to tackle in the future?

Whoa. I’m going to finish my play! Actually, with the conversation that’s happening, I’m about to do an arms training course, which I think is going to be very, very different. I want to feel empowered if I’m going on set if I’m holding any form of weapon or anything like that. So this is obviously with everything that happened with Halyna [Hutchins]. Yeah, I want to feel empowered and I can ask the right questions. I’ve always wanted to write a children’s book. I’ve also always wanted to write a novel; I think there’s something around writing that is calling me. To grow some crops. I want to do some more directing and filmmaking.

What about the perfect storm, all the resources?

I want to see something about Nanny of the Maroons. I want to see something about her. There are some incredible historical figures that haven’t been unearthed yet. I’ve been doing research on this. I don’t wanna give too much away. Definitely, historical figures whose story hasn’t been told yet. And these incredible Black women who have been in the UK and made an impact. But yeah, they’ve not really shone a light on this story yet.

Especially concerning the representation of older Black women.

That’s it. Yeah. Well, with Blacktress — everything that we do is intergenerational. The conversation has to be about the young and old. Our older women are being seen and also for the younger women to understand that they come from a lineage, a culture that is not new. It is ours. You don’t have to reach for it, it just is. And for the innovation and energy of young people and the vitality from young people that I want the elders to be able to hold on to as well. So that’s something that we have to continue having spaces for that to happen.

They have the stories, they have the history that we were going to need going forward.

The keys to unlock everything! As we say, everything is cyclical. Always comes around. We think we’re done with one thing and it comes back ten years later, and the young people are like, Oh my gosh, this thing has happened and the elders are like, Seen it before. So, that space has to continuously be happening.

Hanna is streaming now on Amazon Prime Video. Follow Cherrelle at @cherrelleskeete and Blacktress at @blacktress_uk.

Interview Selah Ella

Photography Kirk Truman

Stylist Emily Tighe

Make up Kenneth Soh c/o The Wall Group